Executive Summary We appreciate the opportunity to comment on the Draft Merger Guidelines (Draft Guidelines) released by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ or Division) . . .

Executive Summary

We appreciate the opportunity to comment on the Draft Merger Guidelines (Draft Guidelines) released by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ or Division) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) (jointly, the agencies), Docket No. FTC-2023-0043. Our comments below mirror the structure of the main body of the Draft Guidelines: guidelines, market definition, and rebuttal evidence. Section by section, we suggest improvements to the Draft Guidelines, as well as background law and economics that we believe the agencies should keep in mind as they revise the Draft Guidelines. Our suggestions include, inter alia, the recission of some of the draft guidelines and the integration of others.

Much of the discussion around the guidelines focuses on whether enforcement should be more or less strict. But the stringency or rigor of antitrust scrutiny is not a simple dial to turn up or down. For example, what should be done with HHI thresholds? It may seem obvious that lower thresholds allow the agencies to challenge more mergers. In a world with limited agency resources, however, that may not be true. Under the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, the agencies did not challenge—much less block—all mergers leading to “moderately concentrated” or even “highly concentrated” markets. If we assume, as the Draft Guidelines appear to, that mergers leading to relatively high-concentration markets are generally more likely to be anticompetitive, lowering the thresholds would result in fewer of such challenges, to the extent that the agencies would necessarily allocate some of their scarce enforcement resources to matters that would not have raised competitive concerns under the thresholds specified in 2010.

Our main recommendations are as follows:

Guideline 1 places increased emphasis on structural presumptions and concentration measures. This rests on the assumption that the economy is becoming more concentrated, that this is problematic, and that lowering the thresholds would help to tackle this problem. But, as our comments explain, this seemingly simple story is not actually so simple. The changes contemplated by guideline 1 thus appear ill-founded. As written, guideline 1 could be used to block mergers without needing to show any actual harms to consumers or sellers/workers. Whether this is the intent or not, the answer should be made explicit. We argue that mergers should not be challenged based on concentration measures alone, given the long-known—but also recently empirically supported—disconnect between concentration measures and competitive harms.

Guideline 2: The guidelines mostly ignore the real distinctions between horizontal and vertical mergers. Guideline 2 is about horizonal mergers, as a footnote suggests, and provides an opportunity to make explicit that horizontal mergers exist, are unique, and will be treated differently than vertical mergers for reasons underlined by the guideline.

Guideline 6: To the extent that guideline 6 goes beyond what is included in guideline 5, it simply adds additional structural presumptions that are not justified by the law or the economics. In a part of the Brown Shoe decision ignored by the Draft Guidelines, the court wrote that “the percentage of the market foreclosed by the vertical arrangement cannot itself be decisive,” yet guideline 6 would make a structural-presumption decision. This is especially problematic in the context of vertical mergers, where the “foreclosure share” does not require an incentive to foreclose. As written, the guideline would treat as inevitable even foreclosure that was highly unprofitable.

Guideline 8: As concentration is not (by itself) harmful to consumers, neither is a trend toward concentration. As with guideline 1, guideline 8 should make explicit whether the intent is that it be used regardless of any harm to consumers. If an industry that has become more concentrated through more competition—as a large, recent economic literature documents is the norm—will the agencies block a merger that increases concentration but does not increase prices? Guideline 8 is especially problematic when paired with the statement that “efficiencies are not cognizable if they will accelerate a trend toward concentration.” This effectively negates any efficiency defense, since any efficiency will allow a merged party to win a larger share of the market. If these customers come from smaller competitors, that will increase concentration.

We conclude by explaining how the Draft Guidelines are not law and that it remains up to the courts whether to follow them. Historically, courts have followed such guidelines, given their reflection of current legal and economic understanding. These Draft Guidelines, by contrast, seem much more geared toward pursuing stronger merger enforcement. Rather than reflect current knowledge, the agencies are seemingly looking to reverse time and return to an outdated set of policies from which courts, enforcers, and mainstream antitrust scholars have all steered away. The net effect of these problems is to undermine confidence in the agency.

I. Guideline 1: Mergers Should Not Significantly Increase Concentration in Highly Concentrated Markets

Draft Guideline 1 of the Draft Merger Guidelines (“Draft Guidelines”)[1] appears to suggest a standalone structural presumption[2] that mergers that “significantly increase” concentration in “highly concentrated” markets are unlawful; and it does so under a lower-threshold Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) for highly concentrated markets than that specified in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, and a lower change in HHI than that specified in the 2010 Guidelines.

Several of these changes are salient. First, the Draft Guidelines replace a threshold HHI for “highly concentrated markets” of 2,500 with one of 1,800. Under the 2010 Guidelines, horizontal mergers that would increase HHI at least 100 points, resulting in an HHI of between 1,500 and 2,500 (inclusive), would be regarded as mergers that “potentially raise significant competitive concerns.” While they might warrant investigation, they would not implicate a structural presumption of illegality.

Second, under the considerably higher thresholds specified in 2010, mergers leading to highly concentrated markets that involved changes in HHI of between 100 and 200 would still be considered among those that “potentially raise significant competitive concerns,” and they would “often warrant scrutiny,” but they would not implicate a presumption of illegality. Only “[m]ergers resulting in highly concentrated markets that involve an increase in the HHI of more than 200 points [would] be presumed to be likely to enhance market power.”

Third, under the 2010 Guidelines, the presumption that mergers “likely to enhance market power” could be “rebutted by persuasive evidence showing that the merger is unlikely to enhance market power.” Draft guideline 1—even with lower thresholds for change and total market concentration, as measured by HHI—identifies no potential for rebuttal of the presumption.

Fourth, the 2010 Guidelines expressly identify mergers that are “unlikely to have adverse competitive effects and ordinarily require no further analysis”; namely, those involving increases in HHI of less than 100 and those resulting in an HHI less than 1,500. The Draft Guidelines do not identify any such mergers, whether under the 2010 thresholds or otherwise.

Fifth, the 2010 thresholds were specified in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines and, as such, applied to horizontal mergers. Other guidelines and agency practice recognized—correctly—that vertical mergers could raise competition concerns. At the same time, they recognized general distinctions between horizontal, vertical, and other “non-horizontal” mergers, such as “conglomerate mergers,” that are absent in—if not repudiated by—the Draft Guidelines. The lower thresholds and altered presumptions of the draft guideline 1 make no mention of horizontal-specific revisions; and, as we discuss below, draft guidelines 5-8 and 10 expressly extend the scope of the Draft Guidelines to vertical and other non-horizontal mergers.

If the Draft Guidelines’ “basis to presume that a merger is likely to substantially lessen competition” is not such a presumption of illegality, or is not so independent of market power, or is rebuttable, then revisions should say so. Also, if the agencies believe that there is any category of mergers that are unlikely to have adverse competitive effects, and unlikely to require further scrutiny, they should say so.

The Draft Guidelines state that this type of structural presumption provides a highly administrable and useful tool for identifying mergers that may substantially lessen competition. Unfortunately, this reasoning overlooks a crucial aspect of the antitrust apparatus (and of all regulation, for that matter): the error-cost framework. Administrability is a virtue, all things considered, but so is accuracy. Any given merger might be anticompetitive, but most are not, and enforcement should not routinely condemn benign and procompetitive mergers for the sake of convenience. As we explain below, the key insight is that policymakers should always consider antitrust enforcement as a whole. In other words, it is never appropriate to look at certain categories of judicial error in isolation (such as authorities wrongly clearing certain mergers). Instead, the challenge is to determine which set of rules and presumptions minimizes the sum of three social costs: false convictions, false acquittals, and enforcement costs.

When this is properly understood, it becomes clear that false negatives are only one part of the picture. It is equally important to ensure that new guidelines do not inefficiently chill or otherwise impede procompetitive deals. This is where proposals to lower current thresholds and alter existing presumptions run into trouble.

A. Should Concentration Thresholds Be Lowered?

Draft guideline 1 puts concentration metrics front and center and introduces new structural presumptions. The Draft Guidelines evince a strong skepticism toward concentration that is unwarranted by the economic evidence. Two sets of questions are related: what, if anything, does the economic evidence say about the new HHI thresholds advanced by the Draft Guidelines? And what does the economic evidence indicate about strong structural presumptions in antitrust analysis?

Should new merger guidelines lower the HHI thresholds? We agree with comments submitted in 2022 by now-FTC Bureau of Economics Director Aviv Nevo and colleagues, who argued against such a change. They wrote:

Our view is that this would not be the most productive route for the agencies to pursue to successfully prevent harmful mergers, and could backfire by putting even further emphasis on market definition and structural presumptions.

If the agencies were to substantially change the presumption thresholds, they would also need to persuade courts that the new thresholds were at the right level. Is the evidence there to do so? The existing body of research on this question is, today, thin and mostly based on individual case studies in a handful of industries. Our reading of the literature is that it is not clear and persuasive enough, at this point in time, to support a substantially different threshold that will be applied across the board to all industries and market conditions. (emphasis added)[3]

Instead of following the economics literature, as summarized above, the Draft Guidelines lower the structural presumptions and add an additional one for when the merged firms share exceeds 30% and the HHI increase exceeds 100.

One argument for this increased emphasis on structural presumptions and concentration measures is that the economy is becoming more concentrated, that this is problematic, and that lowering the thresholds helps to tackle this problem. The following sections explain why the story is not so simple.

B. Empirical Trends in Concentration

The first mistake is to suppose that concentration trends have reached unprecedented levels, that extant levels are generally harmful, and that current undue levels of concentration across the economy are due to lax antitrust enforcement. However, market concentration is not, in itself, a bad thing; indeed, recent research challenging the standard account demonstrates that much observed concentration is driven by increased productivity, rather than by anticompetitive conduct or anticompetitive mergers. In addition, several recent studies show that local concentration—which is the most likely to affect consumers, and where most competition happens—has been steadily decreasing. In fact, as we show, increased concentration at the national level is itself likely the result of more vigorous competition at the local level. Further complicating matters for the “accepted” story (and exacerbated by these national/local distinctions) is the longstanding problem of drawing inferences from national-level concentration metrics for antitrust-relevant markets.

There is a popular narrative that lax antitrust enforcement has led to substantially increased concentration, strangling the economy, harming workers, and saddling consumers with greater markups in the process. Much of the contemporary dissatisfaction with antitrust arises from a suspicion that overly lax enforcement of existing laws has led to record levels of concentration and a concomitant decline in competition.

However, these beliefs—lax enforcement and increased anticompetitive concentration—wither under scrutiny.

1. National versus local competition

Competition rarely takes place in national markets; it takes place in local markets. And although it appears that national-level firm concentration is growing, this effect is driving increased competition and decreased concentration at the local level, which typically is what matters for consumers. The rise in national concentration is predominantly a function of more efficient firms competing in more—and more localized—markets. Rising national concentration, where it is observed, is a result of increased productivity and competition, which weed out less-efficient producers.

This means it is inappropriate to draw conclusions about the strength of competition from national-concentration measures. This view is shared by economists across the political spectrum. Carl Shapiro (former deputy assistant attorney general for economics in the DOJ Antitrust Division under Presidents Obama and Clinton) for example, raises these concerns regarding the national-concentration data:

[S]imply as a matter of measurement, the Economic Census data that are being used to measure trends in concentration do not allow one to measure concentration in relevant antitrust markets, i.e., for the products and locations over which competition actually occurs. As a result, it is far from clear that the reported changes in concentration over time are informative regarding changes in competition over time.[4]

The 2020 report from the President’s Council of Economic Advisors sounds a similar note. After critically examining alarms about rising concentration, it concludes they are lacking, and that:

The assessment of the competitive health of the economy should be based on studies of properly defined markets, together with conceptual and empirical methods and data that are sufficient to distinguish between alternative explanations for rising concentration and markups.[5]

In general, competition is increasing, not decreasing, whether it is accompanied by an increase in concentration or not.

The narrative that increased market concentration has been driven by anticompetitive mergers and other anticompetitive conduct derives from a widely reported literature documenting increased national product-market concentration.[6] That same literature has also promoted the arguments that increased concentration has had harmful effects, including increased markups and increased market power,[7] declining labor share,[8] and declining entry and dynamism.[9]

There are good reasons to be skeptical of the national concentration and market-power data on their face.[10] But even more important, the narrative that purports to find a causal relationship between these data and the depredations mentioned above is almost certainly incorrect.

To begin with, the assumption that “too much” concentration is harmful assumes both that the structure of a market is what determines economic outcomes, and that anyone knows what the “right” amount of concentration is. But as economists have understood since at least the 1970s (and despite an extremely vigorous, but futile, effort to show otherwise), market structure is not outcome determinative.[11]

Once perfect knowledge of technology and price is abandoned, [competitive intensity] may increase, decrease, or remain unchanged as the number of firms in the market is increased.… [I]t is presumptuous to conclude… that markets populated by fewer firms perform less well or offer competition that is less intense.[12]

This view is well-supported, and it is held by scholars across the political spectrum.[13] To take one prominent, recent example, professors Fiona Scott Morton (deputy assistant attorney general for economics in the DOJ Antitrust Division under President Obama), Martin Gaynor (former director of the FTC Bureau of Economics under President Obama), and Steven Berry surveyed the industrial organization literature and found that presumptions based on measures of concentration are unlikely to provide sound guidance for public policy:

In short, there is no well-defined “causal effect of concentration on price,” but rather a set of hypotheses that can explain observed correlations of the joint outcomes of price, measured markups, market share, and concentration.…

Our own view, based on the well-established mainstream wisdom in the field of industrial organization for several decades, is that regressions of market outcomes on measures of industry structure like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index should be given little weight in policy debates.[14]

Furthermore, the national concentration statistics that are used to justify invigorated antitrust law and enhanced antitrust enforcement are generally derived from available data based on industry classifications and market definitions that have limited relevance to antitrust. As Luke Froeb (former deputy assistant attorney general for economics in the DOJ Antitrust Division under President Trump and former director of the FTC Bureau of Economics under President Bush) and Greg Werden (former senior economic counsel in the DOJ Antitrust Division from 1977-2019) note:

[T]he data are apt to mask any actual changes in the concentration of markets, which can remain the same or decline despite increasing concentration for broad aggregations of economic activity. Reliable data on trends in market concentration are available for only a few sectors of the economy, and for several, market concentration has not increased despite substantial merger activity.[15]

Agency experience and staff research in the critical area of health-care competition represents a signal model of the application of applied industrial-organization research to policy development and law enforcement. Notably, the underlying research program has provided solid ground for blocking anticompetitive hospital mergers, while militating against SCP assumptions in provider mergers. Results suggest, for example, that various “the new screening tools (in particular, WTP and UPP) are more accurate than traditional concentration measures at flagging potentially anticompetitive hospital mergers for further review.”[16]

Most important, these criticisms of the assumed relationship between concentration and economic outcomes are borne out by a host of recent empirical studies.

The absence of a correlation between increased concentration and both anticompetitive causes and deleterious economic effects is demonstrated by a recent, influential empirical paper by Sharat Ganapati. Ganapati finds that the increase in industry concentration in non-manufacturing sectors in the United States between 1972 and 2012 is “related to an o?setting and positive force—these oligopolies are likely due to technical innovation or scale economies. [The] data suggests that national oligopolies are strongly correlated with innovations in productivity.”[17] The result is that increased concentration results from a beneficial growth in firm size in productive industries that “expand[s] real output and hold[s] down prices, raising consumer welfare, while maintaining or reducing [these firms’] workforces.”[18] Sam Peltzman’s research on increasing concentration in manufacturing has been on average associated with both increased productivity growth and widening margins of price over input costs. These two effects offset each other, leading to “trivial” net price effects.[19]

Several other recent papers look at the data in detail and attempt to identify the likely cause of the observed national-level changes in concentration. Their findings demonstrate clearly that measures of increased national concentration cannot justify increased antitrust intervention. In fact, as these papers show, the reason for apparently increased concentration trends in the United States in recent years appears to be technological, not anticompetitive. And, as might be expected from that cause, its effects appear beneficial. More to the point, while some products and services compete at a national level, much more competition is local—taking place within far narrower geographic boundaries.

By way of illustration, it hardly matters to a shopper in, say, Portland, Oregon, that there may be fewer grocery-store chains nationally if she has more stores to choose from within a short walk or drive from her home. If you are trying to connect the competitiveness of a market and the level of concentration, the relevant market to consider is local. The same consumer, contemplating elective surgery, may search in a somewhat broader geographic area, but one that is still local, not national, and best determined on a merger-by-merger basis.[20]

Moreover, because many of the large firms driving the national-concentration data operate across multiple product markets that do not offer substitutes for each other, the relevant product-market definition is also narrower. In other words, Walmart’s market share in, e.g., “retail” or “discount” retail implies virtually nothing about retail produce competition. In the real world, Walmart competes for consumers’ produce dollars with other large retailers, supermarkets, smaller local grocers, and local produce markets. It also competes in the gasoline market with other large retailers, some supermarkets, and local gas stations. It competes in the electronics market with other large retailers, large electronic stores, small local electronics stores, and a plethora of online sellers large and small—and so forth. For example, when the FTC investigated the Staples/Office Depot merger, it analyzed a far-narrower market than simply “office supplies” or “retail office supplies”; it found that general merchandisers such as Walmart, K-Mart, and Target accounted for 80% of office-supply sales “in the market for “consumable” office supplies sold to large business customers for their own use.”[21]

This conclusion is not mere supposition: In fact, recent empirical work demonstrates that national measures of concentration do not reflect market structures at the local level. Moreover, recent research published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York concludes that a focus on nationwide trends may be misleading, to the extent that the data omit revenue earned by foreign firms competing in the United States.[22] The authors note that accounting for foreign firms’ sales in the U.S. indicates that market concentration did not increase, but “remained flat” over the 20-year period studied. They argue that increasing domestic concentration was counteracted by increasing market shares associated with foreign firms’ sales.

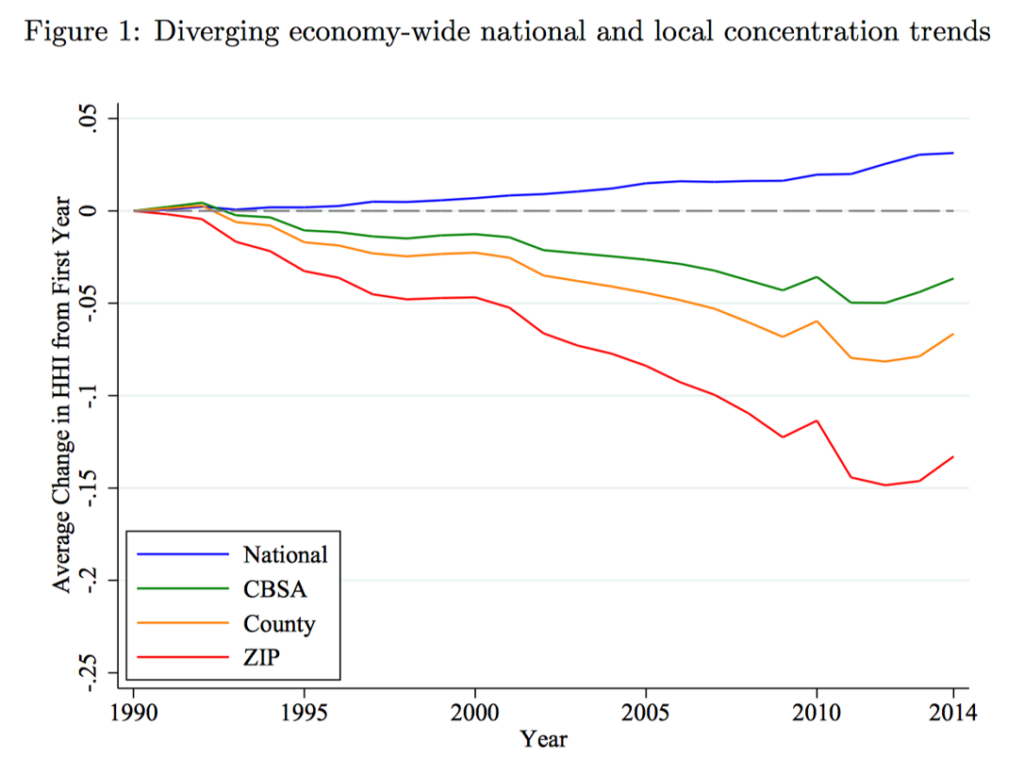

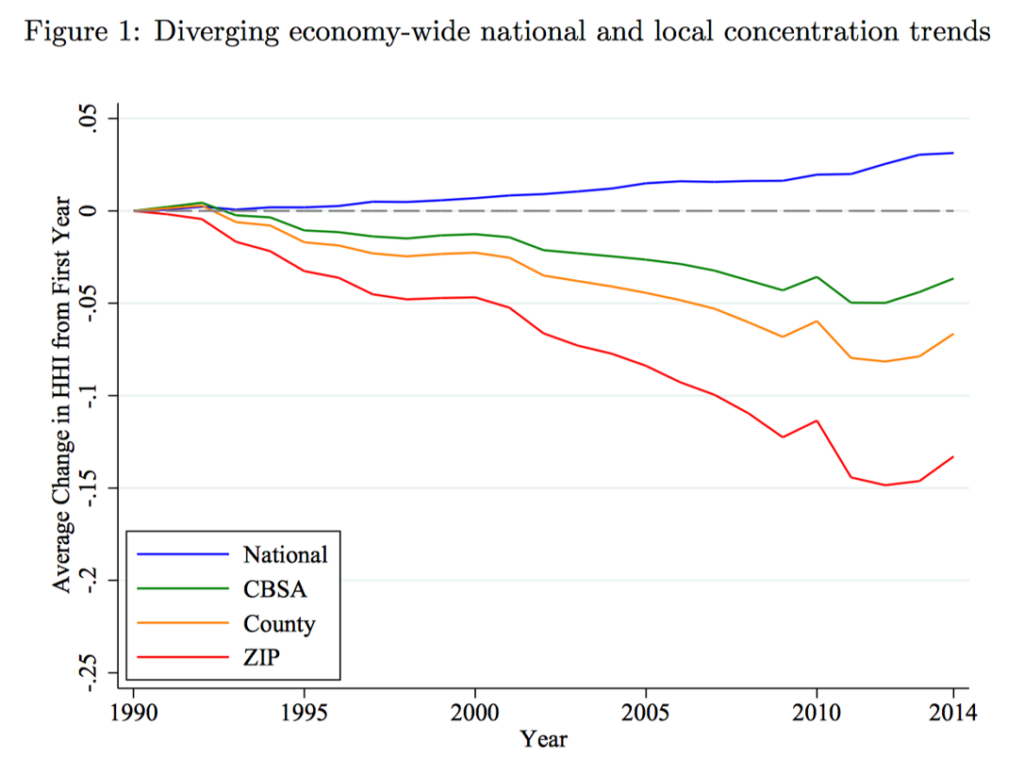

In a recent paper,[23] the authors look at both the national and local concentration trends between 1990 and 2014 and find that:

- Overall, and for all major sectors, concentration is increasing nationally but decreasing locally.

- Industries with diverging national/local trends are pervasive and account for a large share of employment and sales.

- Among diverging industries, the top firms have increased concentration nationally, but decreased it locally.

- Among diverging industries, opening of a plant from a top firm is associated with a long-lasting decrease in local concentration.[24]

Source: Rossi-Hansberg, et al. (2020)[25]

Importantly, all of the above applies not only to product markets, but to labor markets, as well:

The proportion of aggregate U.S. employment located in all SIC 8 industries with increasing national market concentration and decreasing ZIP code level market concentration is 43 percent. Thus, given that some industries have also had declining concentration at both the national and ZIP code level, 78 percent (or over 3/4) of U.S. employment resides in industries with declining local market concentration.[26]

There are disputes about the data used in this study for sales concentration. Some authors argue it more likely reflects employment concentration, instead of sales concentration.[27] It is well-documented that employment concentration has been falling at the local level.[28]

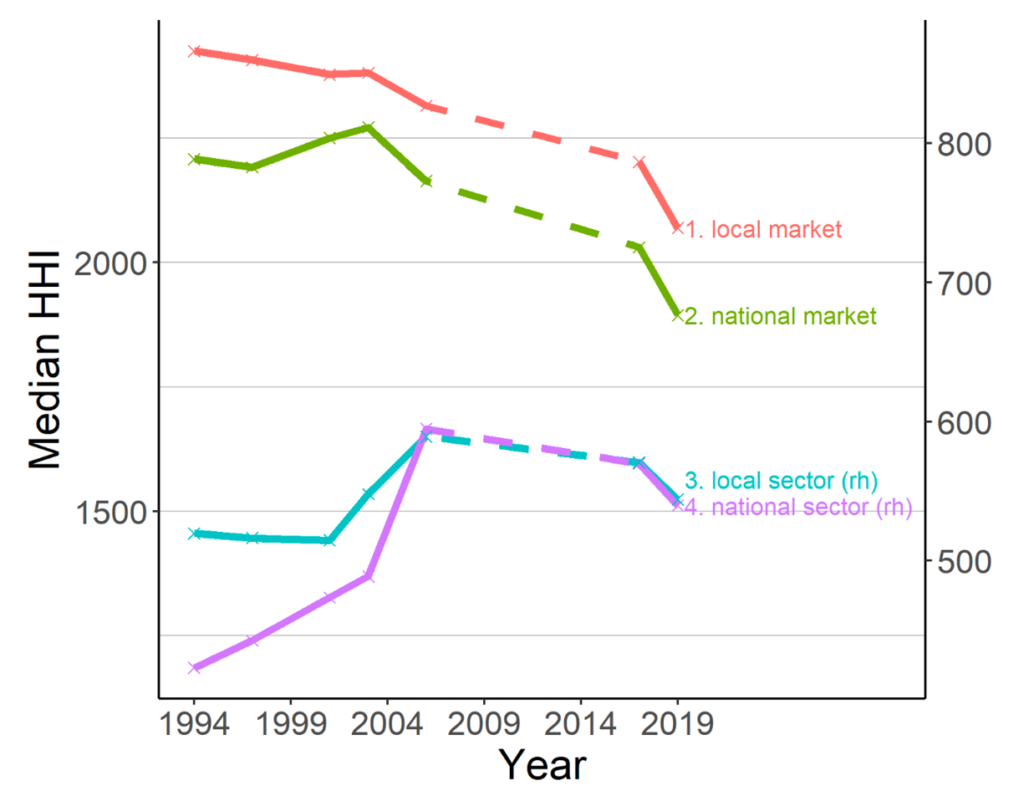

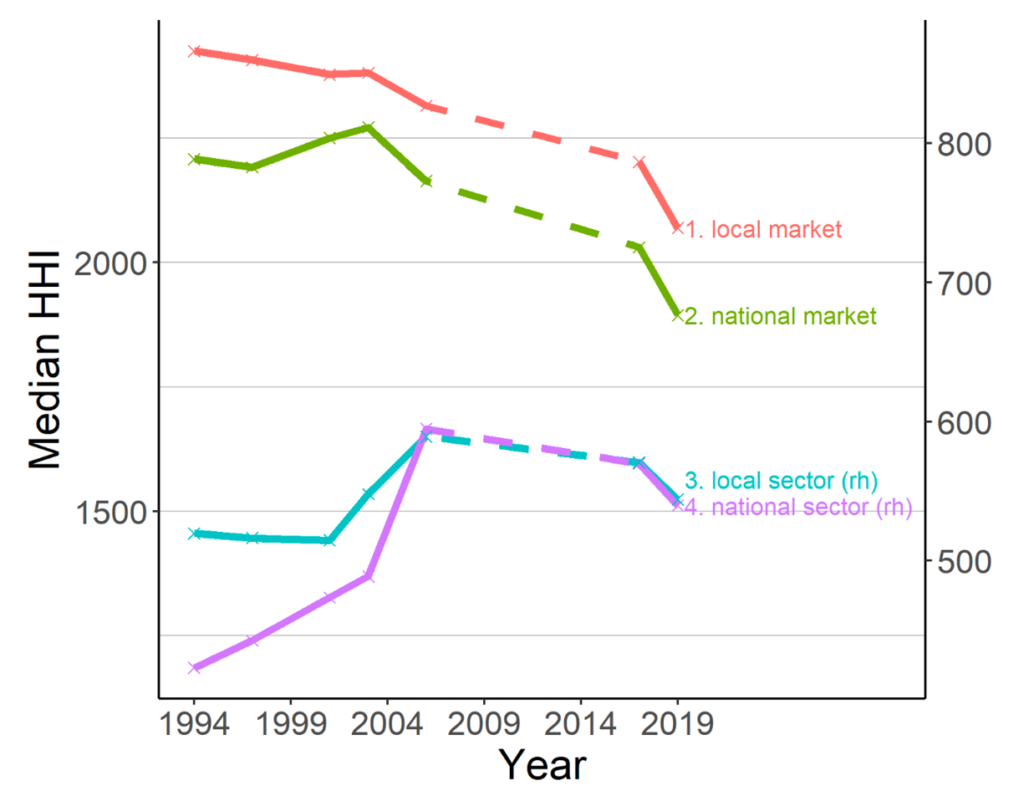

Instead of relying on NAICS or SIC codes, Benkard, Yurukoglu, & Zhang construct concentration measures that are intended to capture consumption-based product markets.[29] They use respondent-level data from the annual “Survey of the American Consumer” available from MRI Simmons, a market-research firm. The survey asks specific questions about which brands consumers buy. They define markets into 457 product markets categories, separated into 29 locations. Product “markets” are then aggregated into “sectors.” Since they know the ownership of different products, even if the brand name is different, they can lump products into companies.

If antitrust enforcers want one paper to get a sense of aggregate trends, this is the one. Their study more closely matches and aggregates antitrust markets than studies that rely on NAICS codes. Against the narrative of the draft guidelines, they find falling concentration at the product-market level (the narrowest product), both at the local and the national level. At the sector level (which aggregates markets), there is a slight increase.

Source: Benkard, et al (2021)[30]

With any concentration measure, one must define the relevant market. As in any antitrust case, this is not trivial when defining markets to measure concentration for the overall economy. Some work, such as Autor, et al., use industries with “time-consistent industry definitions.”[31] Other work finds falling concentration, even at the national level, between 2007 and 2017, when one includes the full sample of industries.[32]

The main implication of these studies for the merger guidelines is not that we need to take a stance on a technical debate in the academic literature, but to recognize that such a healthy debate exists and that it would be unwise to proceed as if we know for certain the direction of empirical trends (and that the agencies can reverse them).

2. Larger national firms can lead to less-concentrated local markets

What is perhaps most remarkable about this data is the unique role large firms play in driving reduced concentration at the local level:

[T]he increase in market concentration observed at the national level over the last 25 years is being shaped by enterprises expanding into new local markets. This expansion into local markets is accompanied by a fall in local concentration as ?rms open establishments in new locations. These observations are suggestive of more, rather than less, competitive markets.[33]

A related paper explores this phenomenon in greater detail.[34] It shows that new technology has enabled large firms to scale production and distribution over a larger number of establishments across a wider geographic space. As a result, these large national firms have grown by increasing the number of local markets they serve, and in which they are relatively smaller players.[35]

What appears to be happening is that national-level growth in concentration is driven by increased competition in certain industries at the local level. “The increasing presence of top ?rms has decreased local concentration in local markets as the new establishments of top ?rms gain market share from local incumbents.”[36] The net effect is a decrease in the power of top firms relative to the economy as a whole, as the largest firms specialize more and are dominant in fewer industries.

These results turn the commonly accepted narrative on its head:

- First, rising concentration, where it is observed, is a result of increased productivity and competition that weed out less efficient producers. This is emphatically a good thing.

- Second, the rise in concentration is predominantly a function of more efficient firms competing in more—and more localized—markets. This means that competition is increasing, not decreasing, whether it is accompanied by an increase in concentration or not.

- Third, in labor markets, the effect of these dynamics is a reduction in monopsony power: “[T]he industrial revolution in services has implications on the employment of workers of different skills across locations. If labor markets are industry speci?c and local, the decline in local concentration of employment caused by the entry of top firms should reduce the monopsony power of employers in small markets.”[37]

Another paper takes a similar approach to analyze the effect of increased firm size on labor-market share.[38] In a complete refutation of the popular narrative, it finds that, while the labor-market power of firms appears to have increased, “labor market power has not contributed to the declining labor share because, despite an overall increase in national concentration, we ?nd that… local labor market concentration has declined over the last 35 years. Most local labor markets are more competitive than they were in the 1970s.”[39]

Further studies have corroborated these findings, noting that, on an industry-by-industry basis, the explanatory power of increasing concentration (or increasing firm size) is extremely weak. For example, while Autor, et al. (2020) attribute the purported decline in the labor share of the U.S. economy to the rise of “superstar” firms,[40] Stanford economist Robert Hall shows that the data is far more nuanced. Thus, comparing the employment shares of ?rms with 10,000 or more workers in the 19 NAICS sectors between 1998 and 2015, Hall finds that:

- “In four of the 19 sectors, very high-employment ?rms declined in importance over the 17-year span of the data. The weighted-average increase across all sectors was only 1.8 percentage points, from 25.3 percent to 27.1 percent. Thus it seems unlikely that rising concentration played much of a role in the general increase in market power.…”; and

- “[T]here is essentially no systematic relation between the mega-firm employment ratio… and the ratio of price to marginal cost.… Over the wide range of variation in the employment ratio, sectors with low market power and with high market power are found, with essentially the same average values. There is no cross-sectional support for the hypothesis of higher markup ratios in sectors with more very large ?rms and thus more concentration in the product markets contained in those sectors.”[41]

3. It is not clear that industry concentration harms consumers

Economists have been studying the relationship between concentration and various potential indicia of anticompetitive effects—price, markup, profits, rate of return, etc.—for decades. There are, in fact, hundreds of empirical studies addressing this topic. Contrary to some common claims, however, when taken as a whole, this literature is singularly unhelpful in resolving our fundamental ignorance about the functional relationship between structure and performance: “Inter-industry research has taught us much about how markets look… even if it has not shown us exactly how markets work.”[42]

Though some studies have plausibly shown that an increase in concentration in a particular case led to higher prices (although this is true in only a minority share of the relevant literature), assuming the same result from an increase in concentration in other industries or other contexts is simply not justified: “The most plausible competitive or efficiency theory of any particular industry’s structure and business practices is as likely to be idiosyncratic to that industry as the most plausible strategic theory with market power.”[43]

As Chad Syverson recently summarized:

Perhaps the deepest conceptual problem with concentration as a measure of market power is that it is an outcome, not an immutable core determinant of how competitive an industry or market is… ??As a result, concentration is worse than just a noisy barometer of market power. Instead, we cannot even generally know which way the barometer is oriented.[44]

This does not mean that concentration measures have no use in merger enforcement. Instead, it demonstrates that market concentration is often unrelated to antitrust enforcement because it is driven by factors that are endogenous to each industry. Enforcers should be careful to not rely too heavily on structural presumptions based around concentration measures, as these may be poor indicators of the instances in which antitrust enforcement is most beneficial to consumers. The Draft Guidelines move in the opposite direction.

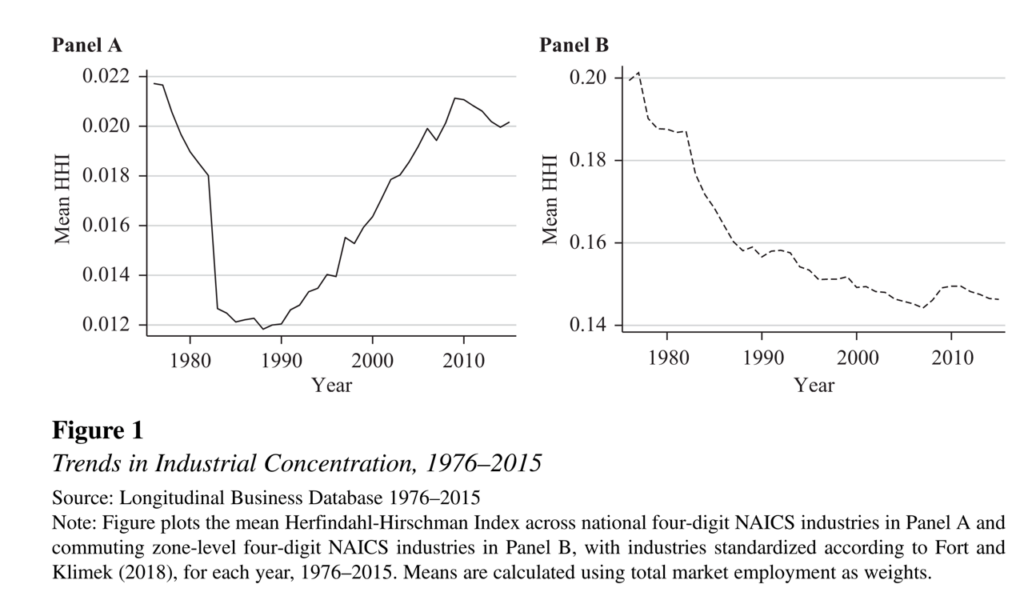

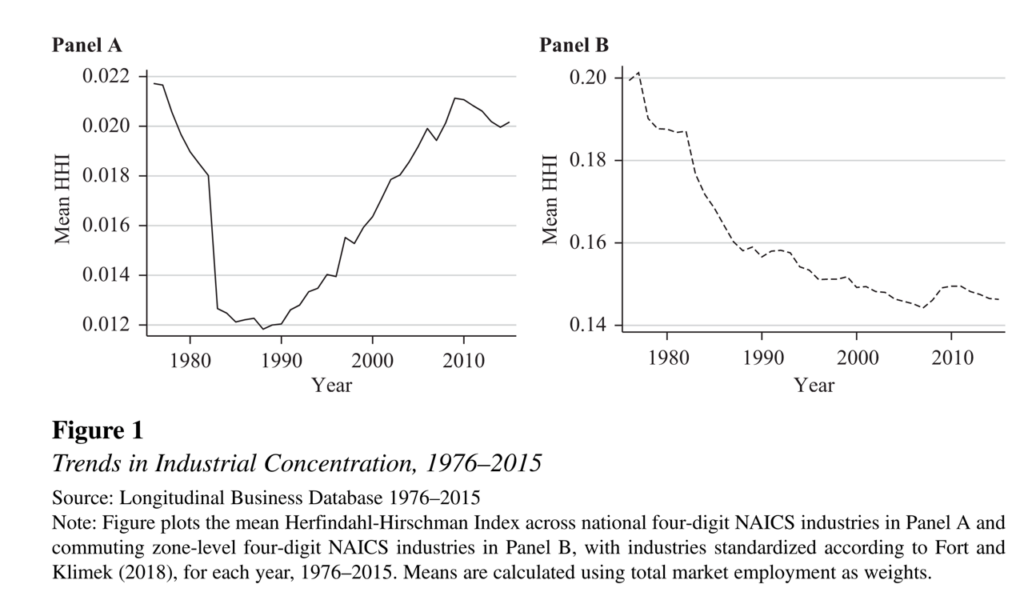

4. Labor market concentration is falling; Should we decrease antitrust attention?

One way to see potential problems with structural presumptions is to consider labor markets. The best data aggregating labor-market concentration finds either low and/or falling concentration over recent decades at the local level. Studies that use administrative data from the Longitudinal Business Database find that local labor-market concentration has been declining, while national concentration has been increasing, across various definitions of “local.”[45]

Source: Rinz (2022)[46]

This fall in concentration has happened even as firms’ labor-market power appears to be rising—which, again, illustrates the disconnect between concentration and market power. According to one recent study in the American Economic Review, while the average labor-market power of firms appears to have increased nationally, “despite the backdrop of stable national concentration, we… find that [local concentration] has declined over the last 35 years.”[47]

Another study uses microdata from the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, mapped to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, which records quarterly employment levels for each establishment in the United States that reports to state-level unemployment insurance departments.[48] They define markets using 6-digit SOC by metropolitan area. They find an average HHI that is relatively stable and low: the employment-weighted level of the employment HHI measure in the private sector is 0.0331.

In short, just as we should not use the low (or falling) average concentration as a reason to decrease HHI thresholds, we should not use high (or rising) average concentration to increase thresholds.

5. Market structure and innovation.

The problem with the focus on market concentration can be seen clearly when looking at innovation. The draft guidelines rightly put increased innovation as a pro-competitive effect on par with increased output or investment, higher wages or improved working conditions, higher quality, and lower prices.[49]

However, this emphasis on innovation is in tension with the guidelines’ excessive focus on market concentration. How does a market’s structure affect innovation? This crucial question has occupied the world’s brightest economists for almost a century, from Schumpeter (who found that monopoly was optimal)[50] through Arrow (who concluded that competitive market structures were key),[51] to the endogenous-growth scholars (who empirically derived an inverted-U relationship between market concentration and innovation).[52] Despite these pioneering contributions to our understanding of competition and innovation, there is a growing consensus that no specific market structure is strictly superior at generating innovation. Just as the SCP paradigm ultimately faltered—because structural presumptions were a weak predictor of market outcomes[53]—so too have dreams of divining the optimal market structure for innovation.[54] Instead, in any given case, innovation depends on a plethora of sector- and firm-specific characteristics that range from the size and riskiness of innovation-related investments to regulatory compliance costs, the appropriability mechanisms used by firms, and the rate of technological change, among many others.

Despite this complex economic evidence, several antitrust agencies, including the FTC and the European Commission, believe they have cracked the innovation-market-structure conundrum. Throughout several recent decisions and complaints, these and other authorities have concluded that more firms in any given market will produce greater choice and more innovation for consumers. This could be referred to as the “Structuralist Innovation Presumption.”[55] This presumption notably plays an important role in the FTC’s recent case against Facebook, where the agency argues that:

Competition benefits users in some or all of the following ways: additional innovation (such as the development and introduction of new features, functionalities, and business models to attract and retain users); quality improvements (such as improved features, functionalities, integrity measures, and user experiences to attract and retain users); and consumer choice…[56]

Unfortunately, the Structuralist Innovation Presumption is a misguided heuristic that antitrust authorities around the globe would do well to avoid, as it is at odds with the mainstream economics of innovation.[57]

There is a vast empirical literature examining the relationship between market structure and innovation. While a comprehensive survey of the literature is beyond the scope of our comments, the top-level findings clearly suggest that the relationship between market structure and innovation is not monotonic, and that it depends on several other parameters. For instance, surveying the econometric literature concerning the effect of industry structure on innovation, Richard Gilbert concludes that it is indeterminate:

Table 6.1 summarizes the conclusions from these interindustry studies for the effects of competition and industry structure on innovation. Unfortunately, these studies do not reach a consensus, other than to note that innovation effects can differ dramatically for firms that are at different levels of technological sophistication. Although some studies find a positive relationship between measures of innovation and competition (alternatively, a negative relationship between innovation and industry concentration), others find that the relationship exhibits an inverted-U, with the largest effects at moderate levels of industry concentration or competition, and at least one study reports a negative relationship between competition (measured by Chinese import penetration) and innovation (measured by citation-weighted patents and R&D investment. One consistent finding is that an increase in competition has less of a beneficial effect, and may have a negative effect, on innovation incentives for firms that are far behind the industry technological frontier.[58]

Along similar lines, high-profile studies reach opposite conclusions. For instance, looking at the semiconductor industry, Ronald Goettler and Brett Gordon find that concentrated market structures lead to higher innovation:

The rate of innovation in product quality would be 4.2 percent higher without AMD present, though higher prices would reduce consumer surplus by $12 billion per year. Comparative statics illustrate the role of product durability and provide implications of the model for other industries.[59]

Mitsuru Igami reaches the opposite conclusion while studying the hard-disk-drive industry:

The results suggest that despite strong preemptive motives and a substantial cost advantage over entrants, cannibalization makes incumbents reluctant to innovate, which can explain at least 57 percent of the incumbent-entrant innovation gap.[60]

Looking at the hospital industry, Elena Patel & Nathan Seegert find a negative relationship between competition and investment:

In particular, hospitals in concentrated markets increased investment by 5.1 percent ($2.5 million) more than firms in competitive markets in response to tax incentives. Further, firms’ investment responses monotonically increased with market concentration.[61]

Finally, some of the most universally recognized articles in this field stem from the empirical research of Aghion and coauthors.[62] Their work famously found that the relationship between product-market competition and innovation had an inverted-U shape. Stated differently, increased product-market competition is associated with higher innovative output, up to a point of diminishing returns.[63] According to some, this strand of research warrants a policy of greater antitrust enforcement, relying upon patents to generate ex post profits for innovators.[64]

This conclusion appears somewhat misguided, as Aghion et al.’s seminal paper paints a far more nuanced picture. The authors’ main finding is that product-market concentration has an ambiguous effect on innovation—on average.[65] This last qualification is often omitted in policy discussions. As a result, what is true for the economy as a whole does not necessarily hold on a case-by-case basis. Some comparatively concentrated industries may score highly in terms of innovation, while some moderately concentrated ones do not.[66] In other words, there are several endogenous factors that affect how increased product-market competition will influence innovation in a given case. For example, the authors show that greater product-market competition is more likely to have a positive effect on innovation in industries where firms are technologically “neck and neck” before an innovation takes places (as opposed to those industries where “laggard” firms can innovate to overtake incumbents).[67] In the first case, more competition mostly decreases pre-innovation rents, while in the second case it has a larger effect on post-innovation rents (this is because increased competition would have little to no effect on laggard firms’ pre-innovation rents, which are likely to be small). [68]

The upshot is that empirical economics do not paint a clear or consistent picture of the relationship between market structure and innovation. Antitrust authorities and courts should thus avoid the presumption that more concentrated-market structures hinder innovation to the detriment of consumers.

6. Market structure and investment: lessons from telecom

As the previous section explained, mergers may lead to diverging price and innovation effect—as increased concentration might sometimes (though certainly not always) increase both market power and innovation output. This is not the only area where price and “non-price” effects may cut in opposite directions. Price competition and investments can also be inversely correlated.

Mergers among mobile-wireless providers provide a rich source of information to evaluate these effects. In a recent paper, ICLE scholars reviewed the sizable empirical literature on this topic, with much of the research focused on so-called “4-to-3” mergers that reduce the number of large, national carriers from four firms to three (though some have also persuasively argued that such a characterization may not be accurate).[69]

Of the 18 studies ICLE reviewed, eight analyzed changes in market concentration across multiple jurisdictions between 2000 and 2015, while 10 analyzed specific mergers. ICLE’s paper also reviewed a more recent study that considered the effects of U.S. market concentration in spectrum ownership on measures of quality.

Of the 10 studies that looked at specific mergers, about half found that short-term prices decreased following a merger, whereas half found that short-term prices increased. Even different studies of the same merger found wildly different effects on short-term prices, ranging from significant price decreases to significant price increases. Thus, looking at these price effects alone, the studies are, collectively, inconclusive.

The ICLE paper identified several reasons for these apparently divergent results, including:

- a lack of common measures of prices and price effects across studies;

- differences in the time period chosen; and

- difficulties accounting for variations in geography, demography, and regulatory regimes among jurisdictions (the latter also creates a potential for endogeneity bias).

Of those studies that considered the effect on long-term investment of such mergers, all found that capital expenditures—a proxy for investment and, presumably, long-term dynamic welfare—increased post-merger.

Indeed, several recent studies that looked more broadly at the effects of market concentration in the mobile-telecommunications industry suggest that increased concentration is correlated with increased investment and may therefore be correlated with greater dynamic benefits. These studies indicate that the highest levels of long-term country-wide investment occurred in markets with three facilities-based operators (though total investment was not significantly lower in markets with four facilities-based operators). In addition, a recent analysis found that U.S. markets with higher concentration of spectrum ownership had faster, more reliable cellular service (reflecting an increase in dynamic welfare effects).

Studies of investment also found that markets with three facilities-based operators had significantly higher levels of investment by individual firms. The implication is that, in such markets, individual firms have stronger incentives to make capital investments that enable long-term competition through expanded infrastructure and technological innovation, which affect the range, quality, and quantity of services provided to consumers. Studies also suggest this effect may be strengthened when the merger results in a more symmetrical market structure (i.e., the various facilities-based providers become more equal in market share). It is argued that increases in the number of competitors in asymmetric markets leads to disproportionately lower levels of investment by smaller firms. Thus, a merger between two smaller firms that results in greater market symmetry could result in higher levels of investment by the merged firms relative to the unmerged entities.

The results of ICLE’s review indicate that a merger that involves products or firms that compete along a variety of dimensions, in addition to price, must evaluate the effects of the merger across these dimensions, as well. In addition, relying on past empirical research to evaluate a current merger may overlook economic, technological, or regulatory changes that diminish the reliability of past experience to inform current events. This review of mobile-wireless-provider mergers reveals a number of factors that should be considered when seeking to understand the likely welfare effects of a given merger. These include:

- Whether the effects to be evaluated are limited to static price effects or also include qualitative measures, such as capital expenditures and other investment in quality of service, suggesting dynamic innovation effects;

- The timeframe over which the effects are evaluated;

- The effects on different tiers of service, especially those measured by hypothetical consumption profiles (known as “baskets” in mobile-wireless-provider mergers);

- The extent to which the effects of previous mergers may confound projected effects of the merger at hand; and

- Whether a transaction occurs during, or even as part of, a transition between different generations of technology (e.g., during an upgrade from 3G to 4G networks).

Further, it is well-known that process and product innovation does not arise solely from new entry; incumbent firms frequently are important sources of innovation, as well as of increased market competitiveness.[70] Dynamic analysis takes entry seriously, but it is much more sensitive to potential entry as a constraint on incumbents than a structuralist view would permit. Thus, for example, an incumbent mobile-wireless provider that offers wide coverage of 4G service must consider the potential capabilities of an existing competitor that currently has only sparse 4G coverage; it must incorporate potential threats from that competitor in its decision matrix when evaluating whether to upgrade its network to 5G in order to retain its customer base. An incumbent’s dominant position can quickly erode thanks to imperfect in-market substitutes, as well as from out-of-market firms that may decide to enter in the future.[71]

When evaluating the merits of a merger, authorities are charged with identifying the effects on the welfare of consumers. Crucially, this analysis must consider not only short-term price effects, but also long-term and dynamic effects, particularly in markets (like mobile telecommunications) in which competition occurs over both price and innovation. Based on the studies that we reviewed, 4-to-3 mergers appear to generate net long-term benefits to consumer welfare in the form of increased investment (presumably—although not conclusively, based on these studies—resulting in increased innovation), while the short-term effects on price are resolutely inconclusive.

II. Guideline 2: Mergers Should Not Eliminate Substantial Competition Between Firms

While it is reasonable to consolidate the horizontal and vertical merger guidelines into one document, the draft essentially writes away the distinction between them. Footnote 30 suggests that Guideline 2 is about horizontal unilateral effects. If so, the application of the guideline to horizontal mergers specifically should be made explicit. Otherwise, readers are left with the impression that the Draft Guidelines intentionally avoid specificity, perhaps hoping to enhance the agencies’ prosecutorial discretion. That would be problematic, notwithstanding the possibility of line-blurring cases. In brief, a significant body of economic literature and judicial precedent recognizes the competitive importance of the distinction, and requires that the agencies treat horizontal and vertical mergers differently.

As Aviv Nevo and colleagues summarized, the distinction is especially important when thinking about efficiencies and other potential merger benefits:

Applying the same sort of skepticism about efficiencies in a vertical merger as in a horizontal merger can amount to assuming away a portion of the economics that is at the heart of the vertical investigation.

One clear example of this dual nature of vertical theories is the model of linear pricing, which generates a raising rivals’ cost incentive and also generates a potential procompetitive incentive in the form of elimination of double marginalization (“EDM”). Not every merger will present facts that fit this particular model. But, if that model is the basis of an investigation, its full range of implications should be considered.[72]

By rejecting—or implying a rejection of—a general distinction between horizontal and vertical mergers, the Draft Guidelines effectively enact a “horizontalization” of merger enforcement. The following subsection explains the importance of explicitly delineating horizontal and vertical mergers at certain points in the Draft Guidelines.

A. Horizontal Mergers Are Different Than Vertical Mergers

Antitrust merger enforcement has long relied on a fundamental distinction between horizontal and vertical mergers (or horizontal and vertical theories of harm, to be more precise). Policymakers widely assume the former are more likely to cause problems for consumers than the latter. However, this distinction increasingly has been challenged by some antitrust scholars and enforcers. In recent years, antitrust authorities on both sides of the Atlantic—and several high-profile scholars—have put forward theories of harm that obscure the traditional distinctions among horizontal, vertical, and conglomerate mergers. This is epitomized by an alarmist 2020 article by Cristina Caffarra and co-authors that portrays nearly all tech mergers as horizontal, based on the supposition that, but for the acquisition, one of the merging firms likely would launch its own competing vertical product..[73] But the claim seems manifestly implausible, and the paper offers no evidence on its behalf. Of course, in a given case, under specific facts and circumstances, a large, diversified tech firm might consider or achieve entry into a vertical market. But a possibility under some facts and circumstances is a far cry from a general likelihood. The implication of this (and other) research is that mergers between firms that are either vertically related or active in unrelated markets routinely or typically have significant horizontal effects.[74] This can be the case, either when merging firms are potential competitors or when they compete in innovation markets (i.e., they have overlapping R&D pipelines, or may have them in the future).[75]

These concerns are compounded in the digital economy, where ostensibly non-competing firms may become competitors on one side of their platforms. For instance, it has been argued that Giphy, which offers a library of gif files, may ultimately compete with Facebook in ad markets.[76] Similarly, it has been claimed that Google’s acquisition of Fitbit—a producer of wearable health-monitoring devices—raises horizontal theories of harm, because Google would otherwise have developed its own wearable devices.[77] Such hypotheticals are sometimes deemed to be “reverse killer acquisitions,” on grounds that acquiring a rival enables the incumbent to not produce a good itself. Endorsing this approach to merger review wholeheartedly would have profound policy ramifications. Indeed, should authorities assume the counterfactual to a merger is that the acquirer will compete with the target directly, then every merger effectively becomes a horizontal one.

The influence of this research can be seen in the FTC’s loss in blocking Meta’s acquisition of Within Unlimited and the ongoing case against Meta, which centers on the company’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram.[78] For the Within case, the FTC wanted to turn a vertical merger (software and hardware) into a horizontal merger between potential competitors. The court was unwilling to accept the claim that, if the Within deal were blocked, Meta would likely develop its own VR fitness app to compete against Supernatural. Meta had no such product poised to enter the market, or even in late-stage development. The contingent probability of timely, competitively significant entry—inherent in a potential competition case—was simply too small or speculative to conclude that Meta was a potential competitor, and was further undermined by internal emails suggesting that they should partner with Peloton—an idea that got so little traction that they never even ran it past Peloton.

At the time of the WhatsApp and Instagram acquisitions, competition authorities around the world tended to analyze them (and the potential theories of harm they might give rise to) primarily as vertical. For instance, looking at Facebook’s purchase of WhatsApp, the European Commission concluded that “while consumer communications apps like Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp offer certain elements which are typical of a social networking service, in particular sharing of messages and photos, there are important differences between WhatsApp and social network services.” This suggested the merging firms were likely active in separate markets.[79] The FTC’s clearance of that deal suggests that the agency largely adhered to the view that the merging entities were not close competitors.[80] Similarly, when the UK CMA reviewed Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram, it concluded that the two firms exercised only weak competitive constraints on each other:

To conclude, there are several relatively strong competitors to Instagram in the supply of camera and photo editing apps, and those competitors appear at present to be a stronger constraint on Instagram than Facebook’s new app.[81]

Reevaluating these deals almost a decade later, the FTC reached a diametrically opposite conclusion. In its Facebook complaint, the agency concluded that:

Failing to compete on business talent, Facebook developed a plan to maintain its dominant position by acquiring companies that could emerge as or aid competitive threats. By buying up these companies, Facebook eliminated the possibility that rivals might harness the power of the mobile internet to challenge Facebook’s dominance….

…As Instagram soared, Facebook’s leaders began to focus on the prospect of acquiring Instagram rather than competing with it….

…In sum, Facebook’s acquisition and control of WhatsApp represents the neutralization of a significant threat to Facebook Blue’s personal social networking monopoly, and the unlawful maintenance of that monopoly by means other than competition on the merits.[82]

While this change of heart could be characterized as the agency updating its position in light of new evidence concerning the nature of competition between the merging firms, there is also a clear sense that times have changed. Indeed, both antitrust agencies and scholars appear more willing to assume (i) that firms could become competitors absent a merger, and (ii) that mergers between them are likely to reflect efforts by the acquirer to anticompetitively maintain its market position. We address both these claims in the subsequent sections.

The most important difference between a horizontal merger and a vertical merger is the merging parties’ relationships with each other. A horizontal merger is between firms that compete in the same product and geographic market. A vertical merger is between firms with an upstream-downstream (e.g., seller-buyer) relationship. These distinctions are well-known and widely accepted. There has been no economic trend that would justify a redefinition of these distinctions.

Drawing on an example provided by Steve Salop, consider a hypothetical orange-juice market with firms that manufacture and engage in the wholesale distribution of orange juice, as well as firms that own the orchards that supply the oranges to be juiced.[83] A merger between manufacturer/wholesalers would be a horizontal merger; a manufacturer/wholesaler’s purchase of a firm owning orchards would be a vertical merger.

A horizontal merger removes a competing firm from the market and thereby eliminates substitute products or firms that produce the products.[84],[85] By definition, horizontal mergers reduce competition, but the attendant harm to consumers may be large, small, or infra-marginal, depending on the facts and circumstances of a given merger; and any consumer harms may be offset by benefits, such as economies of scale and other efficiencies.[86]

In contrast, in most cases, a vertical merger does not eliminate a competing firm from the market and does not involve substitutes.[87] In fact, vertical mergers typically involve complements, such as a product plus distribution or a critical input to a complex device.[88] In Salop’s orange-juice hypothetical, the manufacturer juices oranges, cans the juice, and operates a wholesaling operation to sell the canned juice to retailers. In this example, the wholesaling operations is a complement to the manufacturing process.

Although not necessarily “by definition,” in most cases, vertical mergers are undertaken to achieve efficiencies and reduce costs. For example, through the elimination of double marginalization and the resulting downward pressure on prices, vertical mergers present a stronger likelihood of improving competition than horizontal mergers.[89]

In a statement during the 2018 FTC hearings, FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson concluded that “we know that competitive harm is less likely to occur in a vertical merger than in a horizontal one,” and echoed some of Hoffman’s points:[90]

[I]n contrast to horizontal guidelines, the economics in vertical mergers indicate efficiencies are much more likely. Professor Shapiro went so far as to call them “inherently” likely at our hearing. Given this dynamic, it may be appropriate to presume that certain vertical efficiencies are verifiable and substantial in the absence of strong evidence to the contrary, even if we would not do so in a horizontal merger case.[91]

The economics of horizontal mergers comprises a long, well-established literature of theoretical models and empirical research. In contrast, there are fewer quantitative theoretical models that can be used to predict outcomes in vertical mergers. Moreover, those models that do exist have a far shorter track record than those used to assess horizontal mergers.[92]

Naturally, the real world is much more complicated. For example, Salop points out that some mergers involve firms that are already vertically integrated prior to the merger.[93] In these cases, the merger would involve both vertical and horizontal elements. Such mergers may lead to horizontal and vertical efficiencies that reinforce each other. They also may lead to horizontal and vertical harms that reinforce each other. Or they may lead to mix of horizontal and vertical efficiencies and harms that counteract each other. That may explain why empirical research on vertical mergers, discussed below, can yield sometimes wildly different results—even when using seemingly similar sets of data.

To be sure, there are no economic trends that would lead one to revisit the distinction between horizontal and vertical mergers. Nevertheless, there have been advances in economic theory that have led some to conclude that vertical mergers may not be as beneficial as once thought or that they may lead to anticompetitive consumer harm.

Some critics of the current state of vertical-merger enforcement assert a vertical merger can effectively become a horizontal merger—or have horizontal effects. If that is the case, then it is argued that vertical mergers should be evaluated in the same way as horizontal mergers. According to Salop, “[f]or the type of markets that are normally analyzed in antitrust, the competitive harms from vertical mergers are just as intrinsic as are harms from horizontal mergers.”[94] Thus, a vertically integrated firm faces an “intrinsic incentive”[95] to foreclose downstream competition “by raising the input price it charges to the rivals of its downstream merger partner” in the same way that horizontal firms face “inherent upward pricing pressure from horizontal mergers in differentiated products markets, even without coordination.”[96]

In an implicit acknowledgement of the distinction between horizontal and vertical mergers, Salop describes the competition between an upstream firm and a downstream partner as indirect: “the upstream merging firm that supplies a downstream firm is inherently an ‘indirect competitor’ of the future downstream merging firm. That indirect competition is eliminated by merger. This unilateral effect is exactly parallel to the unilateral effect from a horizontal merger.”[97]

But the two are not “exactly parallel,” of course, because indirect competition is different from direct competition—Salop himself make the distinction. Even in Salop’s telling, the mechanism by which his vertical-leads-to-horizontal theory operates requires that (1) the upstream firm has market power and (2) post-merger, the merged firm forecloses supply or raises costs to the downstream firm’s horizontal rivals. While this is possible, it is not a necessary consequence of the transaction; and the risk of competitive harm, at the very least, must be a function of both the likelihood and degree of foreclosure. The presence of downstream horizontal competitors operates as an immediate and present constraint on the vertically integrated merged firm.

It may be helpful to explain using Salop’s orange-juice hypothetical:

Company A is a manufacturer and wholesale supplier of orange juice to retailers. It seeks to acquire Company B, an owner of orange orchards.… The merged firm may find it profitable to raise the price or cease supplying oranges to one or more rival orange juice suppliers.… This input foreclosure may lessen competition in the wholesale orange juice market, for example, by raising the price or reducing the quality of some or all types of orange juice.[98]

This is an excellent example because it highlights how complex even a straightforward hypothetical of raising rivals’ costs can get. Under the standard formulation, the vertically integrated firm would produce oranges at the orchard’s marginal cost—in theory, the price it pays for oranges would be the same both pre- and post-merger. Under this theory, if the vertically integrated orchard does not sell its oranges to the non-integrated manufacturer/wholesalers, then the other non-vertically integrated orchards will be able to charge a price greater than their marginal cost of production and greater than the pre-merger market price for oranges. The higher price of oranges used by non-integrated manufacturer/wholesalers will then be reflected in higher prices for orange juice sold by the manufacturer/wholesalers.

The merged firm’s juice prices will be higher post-merger because its unintegrated rivals’ juice prices will be higher, thus increasing the merged firm’s profits. The merged firm and unintegrated orchards would be the “winners;” unintegrated manufacturer/wholesalers and consumers would be the “losers.” Under a consumer welfare standard, the result could be deemed anticompetitive. Under a total welfare standard, anything goes.

But this classic example of raising rivals’ costs is based on some strong assumptions. It assumes that, pre-merger, all upstream firms price at marginal cost, which means there is no double marginalization. It assumes all the upstream firm’s products are perfectly identical. It assumes unintegrated firms do not respond by integrating themselves. If one or more of these assumptions is not correct, more complex models—with additional (potentially unprovable) assumptions—must be employed. What begins as a seemingly straightforward theoretical example is now a model-selection problem: which economic models best fit the facts and best predict the likely outcome.

In Salop’s example, it is assumed the merged firm would raise the price or refuse to sell oranges to rival downstream wholesalers. However, if rival orchards charge a sufficiently high price, the merged firm would profit from undercutting its rivals’ orange prices, while still charging a price greater than its own marginal cost. Thus, it is not obvious that the merged firm has an incentive to cut off supply to downstream competitors or charge a higher price. The extent of the pricing pressure on the merged firm to cheat on itself is an empirical matter that depends on how upstream and downstream firms will or might react. Depending on how other manufacturer/wholesalers and orchard firms react, the merged firm’s attempt at foreclosure may have no effect and there would be no harm to competition.

The hypothetical also assumes that commercial juicing is the only use for oranges and that juice oranges are the only thing that can be produced by citrus groves. It is possible that, rather than raising prices or foreclosing competitors, the merged firm would divert some or all of its juice oranges to a “secondary” market, such as the retail market for those who juice at home. They also could convert groves used to grow juice oranges to the production of strains of oranges and other citrus fruits that are sold as fresh produce. Indeed, fresh citrus fruits currently account for 10% of Florida’s crop and 75% of California’s.[99] This diversion would lead to a decline in the supply of juice oranges and the price of this key input would rise.

This strategy would raise the merged firm’s costs along with its rivals. Moreover, rival orchards can respond to this strategy by diverting their own groves from the production of fresh produce citrus to the juice market, in which case there may be no significant effect on the price of juice oranges. What begins as a seemingly straightforward theoretical example is now a complicated empirical matter and raises the antitrust question of whether selling into a “secondary” market constitutes anticompetitive conduct.

Moreover, the merged firm may have legitimate business reasons for the merger and legitimate business reasons for reducing the supply of oranges to juice wholesalers. For example, “citrus greening,” an incurable bacterial disease, has caused severe damage to Florida’s citrus industry, significantly reducing crop yields.[100] A vertical merger could be one way to reduce supply risks. On the demand side, an increase in the demand for fresh oranges would guide firms to shift from juice and processed markets to the fresh market. What some would see as anticompetitive conduct, others would see as a natural and expected response to price signals.

Furthermore, it is not actually the case that the incentive to foreclose downstream rivals is “intrinsic,” nor is it the case that the effect is necessarily deleterious. In fact, as we discuss below, even when foreclosure can be shown, empirical evidence indicates that the consumer benefits from efficiencies tend to be greater than the harms from foreclosure.

A key difference between horizontal and vertical mergers is that any efficiency gains from a horizontal merger are not automatic and must be established. On the other hand, the realization of certain vertical-merger efficiencies, at least from the elimination of double marginalization, is automatic.[101] And, of course, additional merger benefits may be established for any given vertical merger.

The logic is simple: Potentially welfare-reducing vertical mergers are those that involve an upstream firm with market power. Thus, pre-merger, all downstream firms bear presumptively higher input costs. To realize their own profits, they must increase final-product prices to consumers by even more.[102] But after the merger, the merged downstream entity no longer pays the markup. As a result, it “enjoys lower input costs and thus increases its output, thereby increasing welfare.”[103] At the same time, of course, non-merged downstream firms bear a higher input price, and it is an empirical question whether the net consumer welfare effect will be positive or negative. But it is never a question that the two effects operate simultaneously, and that the reduction of double marginalization necessarily occurs. Indeed, it is most likely to arise and to lead to net consumer-welfare benefits precisely where there is the greatest potential for anticompetitive price increases to downstream rivals.[104]

All else being equal, the effect of removing a horizontal competitor by merger is automatic: less competition. That isn’t necessarily bad. It may be offset, and it may also enable innovation, more competition, or other results that benefit consumers. But in the first instance, former head-to-head competitors that merge are no longer competing. With vertical mergers, however, the effect is not to automatically reduce competition (indirect, potential, or otherwise). A vertically integrated firm might (or might not) choose to hurt unaffiliated downstream competitors by more than it benefits its integrated downstream firm—that might (or might not) be feasible and advantageous–but nothing is automatic. Assessing the competitive effect of such a merger necessarily means incorporating an added layer of uncertainty, complexity, and distance between cause and effect. In the absence of a few particular, tenuous, and stylized circumstances, “[i]n this model, vertical integration is unambiguously good for consumers.”[105]

In response, proponents of invigorated vertical-merger enforcement argue, in part, that:

[T]he claim that vertical mergers are inherently unlikely to raise horizontal concerns fails to recognize that all theories of harm from vertical mergers posit a horizontal interaction that is the ultimate source of harm. Vertical mergers create an inherent exclusionary incentive as well as the potential for coordinated effects similar to those that occur in horizontal mergers.[106]

But this fails to resolve anything. Moreover, the “analogy with horizontal mergers is misleading.”[107] It is uncontroversial (and far from “[un]recognized”) that “all theories of harm from vertical mergers posit a horizontal interaction that is the ultimate source of harm.”[108] All this says is that there could be harm of the sort that horizontal mergers might cause. But it does not acknowledge that the likelihood and extent of that harm are different in the vertical and horizontal contexts. Moreover, it does not note that the mechanism by which harm might arise is different and more complex in the vertical case. All in all, the probability of that outcome is lower in the case of a vertical merger, where it is dependent on an additional step that may or may not arrive and that may or may not cause harm.

III. Guideline 4: Mergers Should Not Eliminate a Potential Entrant in a Concentrated Market

The wording of the guideline should be changed to reflect the fact that we are dealing with probabilities, as the body of the guideline makes clear. “Mergers should not eliminate a potential entrant with probable future entry in a concentrated market” would more closely match the body of the guideline.

The distinction between 4.A and 4.B should be eliminated. The only way for a potential entrant to exert competitive pressure is if the current competitors perceive the potential entrant to be a threat. Are the agencies claiming otherwise? Are there firms that no current competitors think about yet somehow still exert competitive pressure on the market? If the agencies mean as much, it should be explicit.

One difficulty with treating all potential competitors like actual competitors is that it assumes that all vertically related (or even non-related) firms could eventually threaten the acquiring incumbent. In other words, potential competition from a particular firm is probabilistic, with the likelihood varying according to the facts and circumstances of the individual case. This forces agencies to make complex assessments regarding the potential future evolution of competition. Beyond the scale that “for mergers involving one or more potential entrants, the higher the market concentration, the lower the probability of entry that gives rise to concern,” the guidelines do not offer guidance about how the relevant probabilities will be assessed.

A. Potential Competition Is Inherently Probabilistic

The uncertainty involved in any merger involving a potential competitor has important ramifications for policymaking. Anticompetitive mergers are, by definition, possible (under the above theories) only when the acquired rival could effectively challenge the incumbent.[109] But these are, of course, only potential challengers; there is no guarantee that any one of them could or would mount a viable competitive threat.[110]

A first important consequence is that, while potential competitors are important constraints on existing markets, they do not generally offer the same degree of constraint as actual competitors.[111] As such, any analysis of a merger involving a potential competitor would have to assess and incorporate the probability of competition.[112] High-quality analysis of the effects of potential competition are few and far between but, according to at least one literature review, a potential competitor may have between one-eighth to one-third the effect on competition as an actual competitor. [113] Likelihoods may vary by industry, product category, and the specific facts and circumstances of the product market and firms at issue. The strength of this competitive constraint also depends on the firms’ perceptions: If both the incumbent and the rival heavily discount the probability of entry, then potential competition is unlikely to affect their behavior.[114]

This leads to a second important issue. Because the loss of a potential competitor will, in expectation, lead to less harm than that of an actual competitor, it is crucial that agencies tailor their responses accordingly. While the traditional remedies for anticompetitive horizontal mergers include divestments or outright prohibition, these remedies may no longer be appropriate in the face of potential competition theories of harm (although such remedies might sometimes remain necessary to fully remove potential anticompetitive harm). Decisionmakers should look at mergers from a cost/benefit standpoint, which, in turn, counsels weighing anticompetitive harms against procompetitive benefits. Because one would expect anticompetitive harms in potential-competition cases to be only a fraction of those in actual-competition cases, there is—all else being equal—a higher likelihood in the former that efficiencies will outweigh harms.

It is not clear how this can be addressed in terms of remedies: neither divestures nor prohibitions can realistically be made probabilistic or conditioned on future market outcomes, as firms could easily game this. At the very least, this probably means judges should set a high evidentiary bar for claims that a merger will reduce potential competition, and agencies should, at the margin, focus more heavily on traditional theories that involve more tangible risks of consumer harm.