Executive Summary In October 2022, the Kroger Co. and Albertsons Cos. Inc. announced their intent to merge in a deal valued at $24.6 billion.[1] Given . . .

Executive Summary

In October 2022, the Kroger Co. and Albertsons Cos. Inc. announced their intent to merge in a deal valued at $24.6 billion.[1] Given the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) increasingly aggressive enforcement stance against mergers and acquisitions, as well as Chair Lina Khan’s previous writings on food retail specifically,[2] some commentators have expressed skepticism that the agency would allow the transaction to proceed—even with divestitures.[3] The FTC and U.S. Justice Department’s (DOJ) recently unveiled draft revisions to the agencies’ merger guidelines further suggest that the agencies plan to challenge more mergers—and to do so more aggressively than under past administrations.[4]

But attempting to block this transaction would go against the analytical framework the FTC has historically used to evaluate similar transactions, as well as the agency’s historical precedent of accepting divestures as a remedy to address localized problems where they arise. Such breaks with the past sometimes happen; our understanding of the law and economics evolves. Unfortunately, these likely breaks from tradition would reflect a failure to consider relevant and significant changes in how consumers shop for food and groceries in today’s world.

The FTC has a long history of assessing retail mergers in a manner significantly at odds with the aggressive approach it is currently signaling. Only one supermarket merger has been challenged in court since American Store’s acquisition of Lucky Stores in 1988: the Whole Foods/Wild Oats merger in 2007.[5] Over the last 35 years, the FTC has allowed every other supermarket merger and most retail-store transactions to proceed with divestitures. Within the last two years alone, these have included Tractor Supply/Orschlein and 7-Eleven/Speedway.[6] The FTC’s historic approach recognizes the reality that competitive concerns regarding supermarket mergers can be readily and adequately remedied by divestitures in geographic markets of concern; indeed, even Whole Foods/Wild Oats was ultimately resolved with a divestiture agreement following a fractured circuit court decision.[7]

The retail food and grocery landscape has changed dramatically since American/Lucky and Whole Foods/Wild Oats. With the growth of wholesale clubs, delivery services, e-commerce, and other retail formats, the industry is no longer dominated by traditional supermarkets. In addition, these changing dynamics have made geographic distance, traffic patterns, and population density decreasingly relevant in a consumer’s choice of where they purchase food and groceries. Today, Kroger is only the fourth-largest food and grocery retailer in the United States, behind Walmart, Amazon, and Costco. If the merger goes through, the combined firm will move into third place in market share, but would still account for just 9% of nationwide sales.[8]

The upshot is that the food and grocery industry is arguably as competitive as it has ever been. Unfortunately, recent developments suggest the FTC may well ignore or dismiss the economic realities of this rapid transformation of the food and grocery industry, substituting instead the outdated approach to market definition and industry concentration signaled by the draft guidelines.[9]

Against this backdrop, our brief highlights five important areas where both the commission and commentators’ stances appear to run headlong into legal precedent that mandates an evidence-based approach to merger review, even as the best available evidence points to a dynamic and competitive grocery industry. The correct understanding of the law and the industry appears entirely at odds with a challenge to the proposed merger.

A. The FTC’s Merger-Enforcement Policy Is on a Collision Course with the Law

The Kroger/Albertsons merger proceeds against a backdrop of tough merger-enforcement rhetoric and actions from the FTC. Recent developments include the publication of aggressive revised merger guidelines, a string of cases brought to block seemingly benign mergers, process revisions burdening even unproblematic mergers, and FTC leadership’s contentious and expansive interpretation of the merger laws. The FTC’s ambition to remake U.S. merger law is likely to falter before the courts, but not before imposing a substantial tax on all corporate transactions—and, ultimately, on consumers.

B. The Product Market Is Broader Than Supermarkets

Because of recent changes in market dynamics, it no longer makes sense to limit the relevant market to supermarkets alone. Rather, consumer behavior in the face of omnipresent wholesale clubs, e-commerce, and local delivery platforms significantly constrains supermarkets’ pricing decisions.

Recent FTC consent orders involving supermarket mergers have limited the relevant product market to local brick-and-mortar supermarkets and food and grocery sales at nearby hypermarkets (e.g., Walmart supercenters), while excluding wholesale-club stores (e.g., Costco), e-commerce (e.g., Amazon), and further-flung stores accessible through online-delivery platforms (e.g., Instacart). This is based on an assertion that the relevant market includes only those retail formats in which a consumer can purchase nearly all of a household’s weekly food and grocery needs from a single stop, at a single retailer, in the shopper’s neighborhood. This is, however, no longer how most of today’s consumers shop. Instead, shoppers purchase different bundles of groceries from multiple sources, often simultaneously.[10] This pattern has substantial implications for supermarkets’ competitive environment.

C. Labor Monopsony Concerns Are Unlikely to Hold Up in Court

More than in any previous retail merger, opponents of the Kroger/Albertsons deal have raised the specter of potential monopsony power in labor markets. But these concerns reflect a manifestly unrealistic conception of labor-market competition. Fundamentally, the market for labor in the retail sector is extremely competitive, and workers have a wide range of alternative employment options—both in and out of the retail sector. At the same time, both Kroger and Albertsons are highly unionized, providing a counterbalance to any potential exercise of monopsony power by the merged firm.

D. The Alleged ‘Waterbed Effect’ Is Not Borne Out by Evidence

Some critics of the merger have speculated that the merged company would be able to exercise monopsony power against its food and grocery suppliers (i.e., wholesalers and small manufacturers), often invoking an economic concept called the “waterbed effect.” The intuition is that the largest buyers may use their monopsony power to negotiate lower input prices from suppliers, leading the suppliers to make up the lost revenue by raising prices for their smaller, weaker buyers.

But these arguments are far from compelling. Much of the discussion of the waterbed effect focuses on harm to competing retailers, rather than consumers. But this is not the harm that U.S. antitrust law seeks to prevent. It is thus not surprising that at least one U.S. court has rejected waterbed-effect claims on grounds that there was no harm to consumers.

E. Divestitures Historically Have Proven an Appropriate and Adequate Remedy

Historically, the FTC has allowed most grocery-store transactions to proceed with divestitures, such as Ahold/Delhaize (81 stores), Albertsons/Safeway (168 stores), and Price Chopper/Tops (12 stores). The extent of the remedies sought depends on the extent of post-merger competition in the relevant local markets, as well as the likelihood of significant entry by additional competitors into the relevant markets.

Despite a long history of divestitures serving as an appropriate and adequate remedy in supermarket mergers, some point to the Albertsons/Safeway merger divestitures to Haggen as evidence that divestitures are no longer an appropriate remedy. But several factors idiosyncratic to Haggen and its acquisition strategy led to the failure of that divestiture, and it does not properly stand for the claim that all supermarket divestitures are doomed. Any divestures associated with the Kroger-Albertsons merger should learn from the Haggen experience, rather than view it as justification to reject reasonable divestiture options that have worked for other mergers.

I. The Agencies Are Trying to Rewrite Merger-Review Standards

The recently published FTC-DOJ draft merger guidelines are a particularly notable backdrop for the Kroger/Albertsons merger, leading many commentators to expect the FTC to take a hardline stance on the deal.[11] Merger case law, however, has not changed much in recent years. Given the merging parties’ apparent willingness to litigate the case, if necessary, the likelihood of a protracted legal battle seems high. As we explain below, at least at first sight, any case against the merger would appear to be largely built on sand, and the commission’s chances of succeeding in court appear slim.

The Clayton Act of 1914 grants the U.S. government authority to review and challenge mergers that may substantially lessen competition. The FTC and DOJ are the two antitrust agencies that share responsibility to enforce this law. Traditionally, the FTC investigates retail mergers, while the DOJ oversees other sectors, such as telecommunications, banking, and transportation.

Before the FTC and DOJ officials appointed by the current administration came into office, the settled practice was for the antitrust agencies to follow the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, which outline the analytical framework and evidence they use to evaluate mergers. The 2010 guidelines describe four major steps of merger analysis:

- The first step is to define the relevant product and geographic markets affected by the merger. The goal is to identify the set of products and regions that are close substitutes to the products and regions sold by the merging parties.

- The second step is to assess the competitive effects of the merger, or how the merger may harm competition in the defined markets.

- The third step is to examine the role of market entry as a potential counterbalance to the competitive effects of the merger. For entry to be sufficient to deter or undo the anticompetitive effects of a merger, it must be timely, likely, and sufficient in scale and scope.

- The fourth and final step is to evaluate the efficiencies generated by the merger, or how the merger may benefit consumers by reducing costs and improving quality.

The antitrust agencies weigh all these factors to determine whether a merger is likely to harm competition and consumers. If they find that a merger raises significant competitive concerns, they may seek to block it or require remedies such as divestitures or behavioral commitments from the merging parties.

Several factors, however, suggest that authorities are unlikely to follow this measured approach when reviewing the Kroger/Albertsons merger.

- Primarily, the FTC and DOJ have recently issued draft revised merger guidelines. The 2023 guidelines have not yet been adopted and are currently open for public comment. Compared to the previous iteration, which guided recent consent decrees, the new guidelines contain more stringent structural presumptions—that is, a presumption that a merger that merely increases concentration (as all horizontal mergers do) by a certain amount violates the law, rather than a more nuanced economic analysis connecting specific market attributes to a likelihood of actual consumer harm.[12]

- Although elements of the above framework are present in the new proposed guidelines, they also incorporate new language reflecting a persistent thumb on the scale that systematically undermines merging parties’ ability to justify their merger. For example, while a presumption of harm is triggered at a certain level of concentration (an HHI of 1800), in markets where there has previously been consolidation (over an unspecified timeframe), an impermissible “trend [toward concentration] can be established by… a steadily increasing HHI [that] exceeds 1,000 and rises toward 1,800.”[13] Traditionally, an HHI under 1500 would be considered “unconcentrated” and presumed to raise no competitive concerns.[14] The notion of a “trend” toward concentration raising particular concern hasn’t been reflected in guidelines since 1968,[15] and reached its apotheosis in Von’s Grocery in 1966[16]—one of the most thoroughly reviled merger cases in U.S. history.[17]

- The FTC had already started to tighten its merger-enforcement policy before the draft revised guidelines were published. Among other actions, the agency brought high-profile cases against the Illumina/GRAIL, Meta/Within, and Microsoft/Activision Blizzard[18] So far, all three challenges have resulted in defeat for the FTC in adjudication. Taken together, these cases suggest the agency is willing to push the law beyond its limits in an attempt to limit corporate consolidation, whatever the actual competitive effect.

- Finally, the FTC’s leadership has been particularly bearish about the potential consumer benefits of corporate mergers and acquisitions. This inclination is reflected in Chair Lina Khan’s assertion that the Clayton Act embodies a “broad mandate aimed at prohibiting mergers even when they do not constitute monopolization and even when their tendency to lessen competition is not certain.”[19]

All of these factors—in concert with the merging parties’ claim that they are prepared to go to court if the FTC decides to block the transaction outright—suggest that there is a particularly high likelihood that the Kroger/Albertsons merger will be challenged and litigated, rather than approved or challenged and settled.

For the reasons outlined in the following sections, however, the FTC is unlikely to prevail in court. The market overlaps between the merging parties are few and can be resolved by relatively straightforward divestiture remedies—which, even if disfavored by the agency, are routinely accepted by courts. Likewise, the FTC’s likely market definition and potential theories of harm pertaining to labor monopsony and purchasing power, more generally, appear speculative at best. The upshot is that the FTC’s desire to bring tougher merger enforcement appears to be on a collision course with the law as it is currently enforced by U.S. courts.

II. The Relevant Market Is Broader Than Supermarkets

The retail food and grocery landscape has changed dramatically since the last litigated supermarket merger. Consumer-shopping behavior has shifted toward more frequent shopping trips across a wide variety of formats, which include warehouse clubs (e.g., Costco), e-commerce (e.g., Amazon), online delivery platforms (e.g., Instacart), limited-assortment stores (e.g., Trader Joe’s and Aldi), natural and organic markets (e.g., Whole Foods), and ethnic-specialty stores (e.g., H Mart), in addition to traditional supermarkets. Because of these enormous changes, the market definition assumed in previous FTC consent orders likely will be—and should be—challenged, given the empirical evidence. This issue brief focuses particularly on the growing importance of warehouse clubs and e-commerce (including online delivery platforms).

A. Recent Trends in Retailing Have Upended the ‘Traditional’ Grocery Market Definition

The FTC is likely to define the relevant product market as supermarkets, which the agency has previously defined as retail stores that enable consumers to purchase all of their weekly food and grocery requirements during a single shopping visit. This market definition includes supermarkets within hypermarkets, such as Walmart supercenters, but excludes warehouse-club stores, such as Costco.[20] Prior consent orders omit any discussion of whether online retailers or delivery services should be included or excluded from the relevant market. This product-market definition has remained mostly unchanged—and mostly unchallenged—since the Ahold/Giant merger a quarter-century ago.[21]

The consent orders exclude warehouse-club stores—as well as hard discounters, limited-assortment stores, natural and organic markets, and ethnic-specialty stores—because these stores are asserted to “offer a more limited range of products and services than supermarkets and because they appeal to a distinct customer type.”[22] In addition, the orders indicate that “supermarkets do not view them as providing as significant or close competition as traditional supermarkets.”[23] Both claims are wrong.

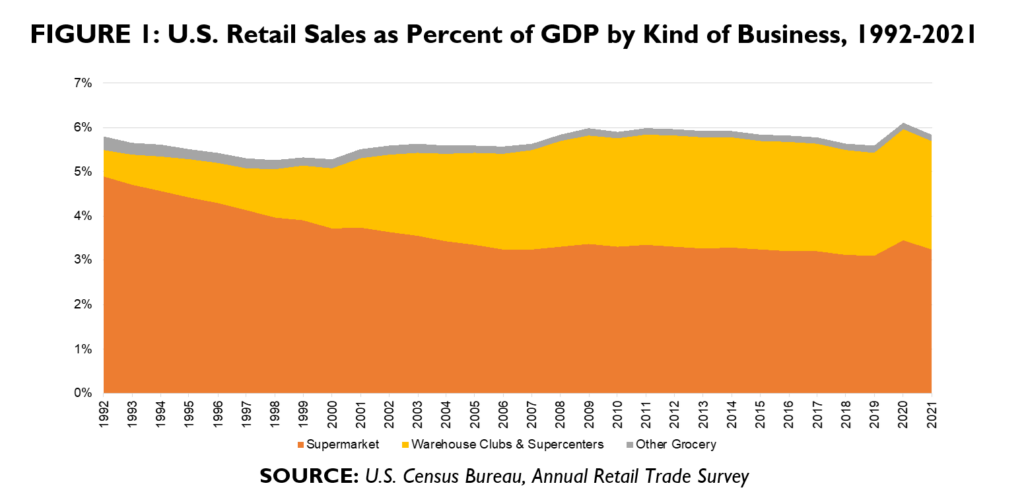

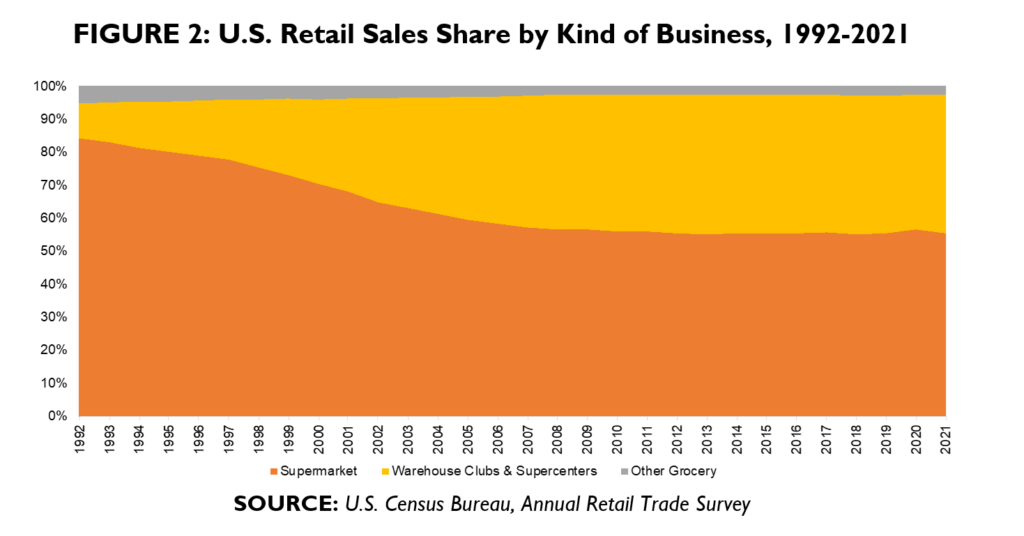

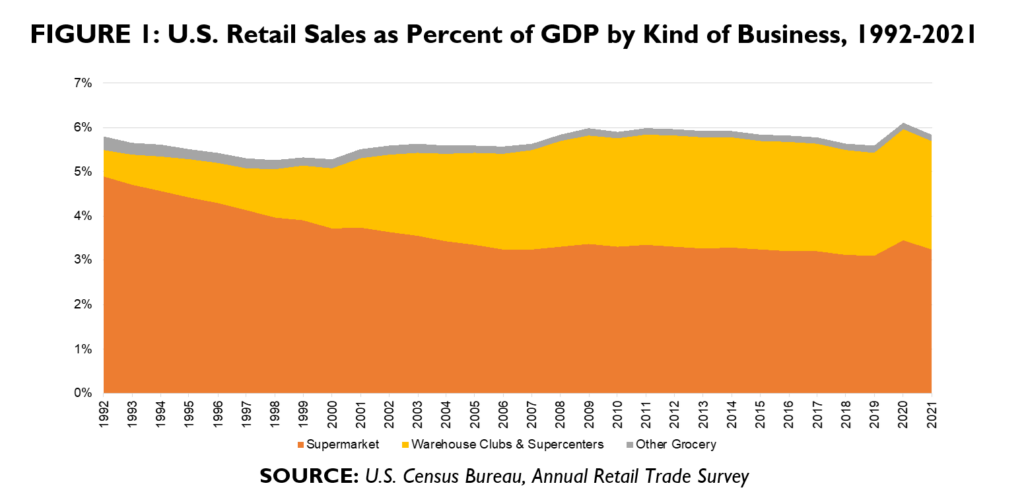

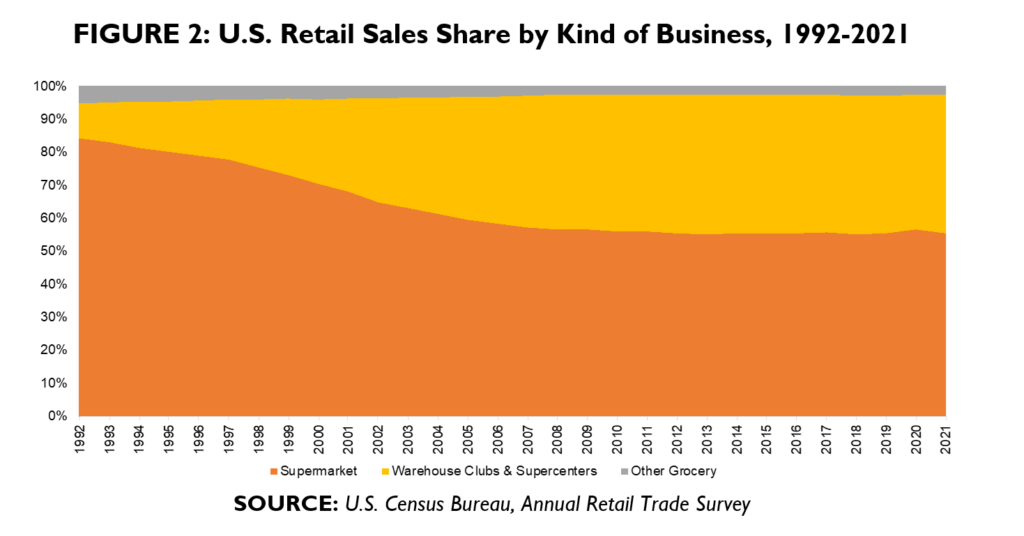

Figure 1 shows that retail sales by supermarkets, warehouse clubs, supercenters, and other grocery stores have been relatively stable at 5-6% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).[24] Figure 2 shows that supermarkets’ share of retail sales dropped sharply from the early 1990s through the mid-2000s, with that share shifting to warehouse clubs and supercenters. These figures are consistent with the conclusion that warehouse clubs and supercenters successfully compete against traditional grocery stores. Indeed, it would be reasonable to conclude that the rise of warehouse clubs and supercenters at the expense of traditional supermarkets is one of the most significant long-run trends in retail.

The retail food and grocery industry has changed dramatically. Below, we note that the average consumer shops for food and groceries more than once a week and shops at more than one retail format in a given week. Since the Ahold/Giant merger in 1998, warehouse clubs and supercenters have doubled their share of retail sales, while supermarkets’ share has dropped by more than 25% (Figure 2). Over the same period, online shopping and home delivery has also greatly changed the market.[25]

Based on these observations, the product-market definition that the FTC has employed in its consent orders over more than two decades is likely to be—and should be—challenged to include warehouse clubs, in addition to accounting for online retail and delivery.

B. The Once-a-Week Shopper Is No Longer the Norm

In the past, the FTC has specified that, for a firm to be in the relevant market of “supermarkets,” it must be able to “enable[e] consumers to purchase substantially all of their weekly food and grocery shopping requirements in a single shopping visit.”[26] This definition suffers from several deficiencies.

The first deficiency is that this hypothetical consumer behavior is at odds with how many or most consumers behave today.

- Surveys conducted by the Food Marketing Institute and The Hartman Group report the average shopper makes 1.6 weekly trips to buy groceries.[27]

- Surveys conducted by Drive Research show the average household makes an average of 8.1 grocery shopping trips a month, or around two trips a week.[28]

There is no evidence that consumers view retailers who provide one-stop-shopping for an entire week’s food and grocery needs as distinct from other retailers who provide food and groceries. In fact, evidence suggests that many consumers “multi-home” across several different retail categories.

- Survey data published by Drive Research indicate that many households spread their shopping across grocery stores, mass merchants, warehouse clubs, independent grocery stores, natural and specialty grocery stores, dollar stores, and online retailers.[29]

- Acosta, a sales and marketing consulting firm, reports that 76% of consumers shop at more than one retailer a week and about one-third “retail hop” among three or more retailers a week for groceries and staples.[30]

- Research from the University of Florida that found, in 2017, an average consumer visited 3.2 to 4.3 different formats of food outlets a month, depending on income level.[31]

Thus, even if one-stop weekly food and grocery shopping at single retailers was once typical, the evidence indicates such a phenomenon is much less common today.

C. Supermarkets Compete with Warehouse Clubs

The FTC’s consent orders provide four reasons to exclude warehouse clubs from the relevant market that includes supermarkets:

- They offer a “more limited range of products and services” than supermarkets;

- They “appeal to a distinct customer type” from supermarket customers;

- Shoppers do not view warehouse clubs as “adequate substitutes for supermarkets;” and

- Supermarkets do not view warehouse clubs as “significant or close competition,” relative to other supermarkets.[32]

In contrast to these conclusions, there is widespread recognition that warehouse clubs impose significant competitive pressure on supermarkets. Indeed, the evidence indicates that supermarkets do consider wholesale clubs to be competitors and vice versa.[33]

- The National Academies of Sciences concludes that, over time, the entry and growth of warehouse clubs, superstores, and online retail has “blurred” the distinctions between retail formats.[34] More importantly for merger-review analysis, the National Academies concludes the retail sector is “highly competitive,” in part because of the entry and growth of warehouse clubs, superstores, and online retail.[35]

- Based on their empirical analysis, Paul Ellickson and co-authors conclude that warehouse clubs are “relevant substitutes” for supermarkets, even when the club stores are outside the geographic area typically used by the FTC in merger reviews.[36]

- Prior to her appointment as FTC chair, Lina Khan and her co-author concluded that competition from warehouse clubs “fueled” grocery mergers in the late 1990s.[37]

The FTC’s consent orders note that warehouse clubs offer a “more limited range of products and services” than supermarkets. The orders identify products sold at supermarket as “including, but not limited to, fresh meat, dairy products, frozen foods, beverages, bakery goods, dry groceries, detergents, and health and beauty products.”[38] The annual reports for Costco, Walmart (Sam’s Club), and BJ’s, however, indicate each company offers the same range of products the FTC consent orders identify as being offered by supermarkets. If warehouse clubs offer similar products, see themselves as competing with supermarkets, and customers view them as substitutes, warehouse clubs must be in the same market.[39]

D. E-Commerce Has Changed the Food Landscape

Since the Ahold/Giant merger in 1998, online shopping and home delivery have grown from niche services serving only 10,000 households nationwide to a landscape where approximately one-in-eight consumers purchase groceries “exclusively” or “mostly” online.[40] This shift has increased competition and innovation in the supermarket industry, as traditional supermarkets have adapted to changing consumer preferences and behaviors by offering more delivery and pickup options, expanding their online assortments, and enhancing their digital capabilities.[41] Some have invested in their own e-commerce platforms and many have partnered with such third-party providers as Instacart, Shipt, and Peapod.[42]

One might surmise that e-commerce simply replaced in-person shopping, but with the same stores competing. This is not what has happened. E-commerce has also increased competition by bringing in new companies with which traditional stores need to compete (e.g., Amazon) and by increasing the options available to consumers through services like Instacart, which allow for direct price and product comparisons among many stores. Each of these innovations has blurred the lines between brick-and-mortar food and grocery retailers and e-commerce, as well as the lines between supermarkets and other retail formats.

In addition, the rapid growth of e-commerce and delivery services make distance, traffic patterns, and population density decreasingly relevant in a consumer’s choice of where they purchase food and groceries. Dimitropoulos and co-authors note (1) the presence of warehouse clubs expands the relevant geographic market, (2) online delivery options expand the geographic market “far away,” and (3) online food and grocery purchases can be delivered from fulfilment centers, as well as from traditional stores.[43]

Because of these observations, the product market-definition that has been employed in the FTC’s consent orders over more than two decades is likely to be—and should be—challenged to include warehouse clubs and to account for online retail and delivery.

III. The Merger Is Unlikely to Increase Labor Monopsony Power

In recent years, there has been more and more emphasis in antitrust discussions placed on labor markets and possible harms to workers. The recent draft merger guidelines added an explicit section on mergers that “May Substantially Lessen Competition for Workers or Other Sellers.”[44] Before the guidelines even, some writers predicted the FTC will push a case on labor competition.[45] While, in theory, antitrust harms can occur in labor markets, just as in product markets, proving that harm is more difficult.

An important fact about this merger is that both companies have many unionized workers. Around two-thirds of Kroger employees[46] and a majority of Albertsons employees[47] are part of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), a union representing 1.3 million members. Even if the merger would increase labor monopsony power in the absence of unions, the FTC will have to acknowledge the reality of the unions’ own bargaining power.

Delegates of the UFCW unanimously voted to oppose the merger. [48] Rather than monopsony power or lower wages, however, the union’s stated reason for their opposition was lack of transparency.[49] While lack of transparency may be problematic for the UFCW members, it does not constitute an antitrust harm. Kroger, on the other hand, has contended that the merger will benefit employees, citing a commitment to invest an additional $1 billion toward increased wages and expanded benefits, starting from the day the deal closes.[50] As with most announced goals, however, there is no enforcement mechanism for this commitment at present, although one could be litigated.

Rather than relying on proclamations from any of the parties, we need economic analysis of the relevant labor markets, asking the types of questions raised above surrounding the output markets. A policy report from Economic Policy Institute estimates that “workers stand to lose over $300 million annually” from the merger.[51] But the report uses an estimate of the correlation between concentration (HHI) in labor markets and wages to arrive at that estimate. While academic research may benefit from such an estimate, it is unhelpful in merger analysis. As a long list of prominent antitrust economists recently wrote, “regressions of price on HHI should not be used in merger review… [A] regression of price on the HHI does not recover a causal effect that could inform the likely competitive effects of a merger.”[52]

Any labor case would require showing the merger would harm workers by reducing their bargaining power. For most workers involved, there are still many potential employers competing. While the exact job-to-job switches are unknown, press releases during the pandemic highlighted how Kroger was hiring workers from a wide variety of companies and industries—from hospitality (Marriott International) to restaurants (Waffle House) to food distribution (Sysco).[53] While there are no publicly available data on worker flows between different companies, economist Kevin Murphy explained that if you ask “where do people go when they leave, often you’ll find no more than 5 percent of them go to any one firm, that they go all over the place. And some go in the same industry. Some go in other industries.”[54]

If, as is likely, an overwhelming majority of Kroger’s workers’ next best option (what they would do if a store closed) was not an Albertsons store but something completely outside of food and grocery stores, the merger would not take away those workers’ next best option. If true, the merger cannot be said to increase labor monopsony power to the extent necessary to justify blocking a merger.

IV. ‘Waterbed Effects’ Are Highly Speculative

One antitrust harm that has been discussed frequently in recent years is the so-called “waterbed effect,” in which “price reductions are negotiated with suppliers by larger buyers and result in higher prices being charged by suppliers to smaller buyers.”[55] The waterbed effect is not unique to mergers but can apply any time there is differential buyer-market power. The firm with more market power gets a good deal and its competitors are harmed. Long before the proposed merger, but still in the context of retail, people were writing about the waterbed effect of Walmart.[56]

In the context of the Kroger/Albertsons merger, critics have again raised the possibility of a waterbed effect. Michael Needler Jr.—the president and chief executive of Fresh Encounter, a chain of 98 grocery stores based in Findlay, Ohio—raised the possibility in a U.S. Senate hearing on the merger.[57] He was also quoted by The New York Times, saying:

When the large power buyers demand full orders, on time and at the lowest cost, it effectively causes the water-bed effect. They push down, and the consumer packaged goods companies have no option but to supply them at their demands, leaving rural stores with higher costs and less availability to products.[58]

In a letter to the FTC, the American Antitrust Institute raised several concerns about the merger and argued that:

The waterbed effect is likely to worsen with Kroger-Albertsons enhanced buyer power post-merger, with adverse effects on the ability of independent grocers to compete in a tighter oligopoly of large grocery chains.[59]

If there is a waterbed effect, some firms will have lower wholesale prices, and some will have higher prices. Both will be partially passed on to consumers. While no doubt frustrating for small retailers, it is unclear whether competing for lower prices and more attention is a normal part of the competitive process, or whether it is anticompetitive, and policy could be used stop it. For example, if one firm is easier to deal with—either because they are more efficient or just more pleasant to interact with—sellers will switch to that firm and correspondingly demand higher returns from the other buyers. Moreover, even if we identify differential prices because of a waterbed effect, it would not imply that there has been any harm to consumers.[60]

While the waterbed theory has attracted the interest of some academics and policymakers, its relevance for antitrust is a different matter. There is a reason that courts have been skeptical. In particular, the court noted that the harms associated with the waterbed theory are borne by competing firms, rather than consumers or competition writ large.[61] Moreover, the court observed that actions taken by firms to avoid any possible harms from a hypothesized waterbed effect (e.g., by purchasing inputs from alternative suppliers) demonstrates a lack of—rather than presence of—monopsony power. The United Kingdom competition authority has evaluated “waterbed effect” allegations in at least two supermarket mergers and found no evidence indicating any anticipated effects of the mergers on input prices that would harm consumers.[62]

V. Remedies Can Solve Any Remaining Competitive Concerns

While the above sections argue that the FTC will have a hard time making a case that the merger is anticompetitive overall, there may be some specific geographic markets where concerns remain. In the face of such concerns, the FTC historically has allowed most supermarket transactions to proceed with divestitures, such as Ahold/Delhaize (81 stores), Albertsons/Safeway (168 stores), and Price Chopper/Tops (12 stores).[63] The extent of the remedies sought depends on the extent of post-merger competition in the relevant markets, as well as the likelihood of entry by additional competitors.[64] Dimitropoulos and coauthors noted that most divestitures required by recent consent orders in recent supermarket mergers have occurred in geographic markets with fewer than five remaining competitors.[65]

In recent merger consent orders, divested stores have been acquired by both retail supermarkets and wholesalers with retail outlets, including Publix, Supervalu, Big Y, Weis, Associated Wholesale Grocers, Associated Food Stores, and C&S Wholesale Grocers.[66] Several of these companies have been expanding—in some cases outside of their “home” territories. For example, Publix is a Florida-based chain that operates nearly 1,350 stores in seven southeastern states.[67] Publix expanded to North Carolina in 2014, Virginia in 2017, and has announced plans to expand into Kentucky this year.[68] Weis Markets is a Pennsylvania-based chain that operates more than 200 stores in seven northeastern states.[69] Last year, the company announced plans to spend more than $150 million on projects, including new retail locations and upgrades to existing facilities.[70] There are also many smaller stores that have proven successful and possible candidates for a few stores. For example, Rochester, New York-based Wegmans has entered Washington, D.C., Delaware, and Virginia over recent years.[71]

A. The Haggen Divestiture Can Be Avoided

Despite a long history of divestitures serving as an appropriate and adequate remedy in supermarket mergers, some point to the Albertsons/Safeway merger divestitures to Haggen as evidence that divestitures are no longer an appropriate remedy.[72] But several factors idiosyncratic to Haggen and its acquisition strategy led to failure, rather than the divestiture itself.

In 2014, the parent company of Albertsons announced plans to purchase rival food and grocery chain Safeway for $9.4 billion. During its merger review, the FTC identified 130 local markets in western and mid-western states where it alleged the merger would be anticompetitive.[73] In response, Albertsons and Safeway agreed to divest 168 supermarkets in those geographic markets.[74] Haggen Holdings LLC was the largest buyer of the divested stores, acquiring 146 Albertsons and Safeway stores in Arizona, California, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.

Following its acquisition of the divested stores, Haggen almost immediately encountered numerous problems at the converted stores. Consumers complained of high prices, and sales plummeted at some stores. The company struggled and began selling some of its stores. Less than a year after the FTC announced the divestiture agreement, Haggen filed for bankruptcy. Following the bankruptcy, Albertsons bought back 33 of the stores it had divested in its merger with Safeway.

Unique factors indicate Haggen may not have been an appropriate buyer for the divested stores. Before acquiring the divested stores, Haggen was a small regional chain with only 18 stores, mostly in Washington State. The acquisition represented a ten-fold increase in the number of stores the company would operate. While Haggen was once an independent family-owned firm, when it acquired the divested stores, the company was owned by a private investment firm that used a sale-leaseback scheme to finance the purchase. Christopher Wetzel notes that Haggen failed to invest sufficiently in the marketing necessary to create brand awareness in regions where Haggen had not previously operated.[75] Such issues would need to be avoided in any future divestitures; experience shows they can be.

The problems with the Haggen divestiture need not be repeated. As explained above, there are many companies of various sizes that have the capabilities and desire to expand. While the relevant product and geographic markets for supermarket mergers has shifted enormously over the past few decades, divestitures remain an appropriate and adequate remedy for any competitive concerns. The FTC has knowledge and experience with divestiture remedies and should have a good understanding of what works. In particular, firms acquiring divested assets should have an adequate cushion of capital, experience with the market conditions in which the stores are located, and the operational and marketing expertise to transition customers through the change.

[1] Press Release, Kroger and Albertsons Companies Announce Definitive Merger Agreement, Kroger (Oct. 14, 2022), https://ir.kroger.com/CorporateProfile/press-releases/press-release/2022/Kroger-and-Albertsons-Companies-Announce-Definitive-Merger-Agreement/default.aspx.

[2] In an article written with Sandeep Vaheesan before she became chair of the FTC, Lina Khan expressed disdain for grocery-industry consolidation and deep skepticism of even the best divestiture packages. See Lina Khan & Sandeep Vaheesan, Market Power and Inequality: The Antitrust Counterrevolution and Its Discontents, 11 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 235, 254 (2017) (“Retail consolidation has enabled firms to squeeze their suppliers… and led to worse outcomes for consumers.”) & 289 (“Even if divestitures could be perfectly tailored and if they preserved competition in narrow markets in every instance, they would fail to advance the citizen interest standard.”).

[3] See, e.g., David Dayen, Proposed Kroger-Albertsons Merger Would Create a Grocery Giant, The American Prospect (Oct. 17, 2022), https://prospect.org/power/proposed-kroger-albertsons-merger-would-create-grocery-giant; Richard Smoley, Kroger, Albertsons, and Lina Khan, Blue Book Services (May 2, 2023), https://www.producebluebook.com/2023/05/02/kroger-albertsons-and-lina-khan.

[4] U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, Draft Merger Guidelines (Jul. 19, 2023), available at https://www.justice.gov/d9/2023-07/2023-draft-merger-guidelines_0.pdf. See also Gus Hurwitz & Geoffrey Manne, Antitrust Regulation by Intimidation, Wall St. J. (Jul. 24, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/articles/antitrust-regulation-by-intimidation-khan-kanter-case-law-courts-merger-27f610d9.

[5] Prior to Whole Foods/Wild Oats, the last litigated supermarket merger was the State of California’s 1988 challenge to American Store’s acquisition of Lucky Stores. Several retail mergers have been challenged in court, however, such as Staples/Office Depot in 2015. See Press Release, FTC Challenges Proposed Merger of Staples, Inc. and Office Depot, Inc., Federal Trade Commission (Dec. 7, 2015), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2015/12/ftc-challenges-proposed-merger-staples-inc-office-depot-inc.

[6] This includes approving Albertsons/Safeway (2015), Ahold/Delhaize (2016), and Price Chopper/Tops (2022). See Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Order to Aid Public Comment, In the Matter of Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., AB Acquisition, LLC, and Safeway Inc. (File No. 141 0108) (Jan. 27, 2015) available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/150127cereberusfrn.pdf; Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Order to Aid Public Comment, In the Matter of Koninklijke Ahold N.V. and Delhaize Group NV/SA (File No. 151-0175) (Jul. 22, 2016), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/160722koninklijkeanalysis.pdf; Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Order to Aid Public Comment, In the Matter of The Golub Corporation and Tops Markets Corporation (File No. 211-0002, Docket No. C-4753) (Nov. 8, 2021), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/2110002pricechoppertopsaapc.pdf.

[7] Decision and Order, In the Matter of Whole Foods Market, Inc., (Docket No. 9324) (May 28, 2009), available at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cases/2009/05/090529wfdo.pdf; FTC v. Whole Foods Market, 548 F.3d 1028 (D.C. Cir. 2008).

[8] Number based on authors’ calculations, using data from Progressive Grocer Staff, 90th Annual Report, Progressive Grocer (May 2023), https://progressivegrocer.com/crossroads-progressive-grocers-90th-annual-report.

[9] U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, supra note 44.

[10] See, e.g., George Kuhn, Grocery Shopping Consumer Segmentation, Drive Research (2002), available at https://www.driveresearch.com/media/4725/final-2022-grocery-segmentation-report.pdf.

[11] Supra note 3.

[12] For instance, the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) at which mergers are deemed problematic has been lowered from 2500 (and a post-merger increase of 200) to 1800 (and a post-merger increase of 100). Likewise, combined market shares of more than 30% are generally deemed problematic under the new guidelines (if a merger also increase the market’s HHI by 100 or more). The revised guidelines also focus more heavily on monopsony and labor-market issues. See U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, supra note 4, at 6-7.

[13] Id. at 21.

[14] See U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines (Aug. 19, 2010) at §5.3 , available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010#5c.

[15] See U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Merger Guidelines (1968) at 6-7, available at https://www.justice.gov/archives/atr/1968-merger-guidelines.

[16] United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270 (1966).

[17] See, e.g., Robert H. Bork, The Goals of Antitrust Policy, 57 Am. Econ. Rev. Papers & Proceedings 242 (1967) (“In the Von’s Grocery case a majority of the Supreme Court was willing to outlaw a merger which did not conceivably threaten consumers in order to help preserve small groceries in the Los Angeles area against the superior efficiency of the chains.”)

[18] FTC v. Illumina, Inc., U.S. Dist. LEXIS 75172 (2021); FTC v. Meta Platforms Inc., U.S. Dist. LEXIS 29832 (2023); FTC v. Microsoft Corporation et al., No. 23-cv-02880-JSC (N.D. Cal. Jul. 10, 2023), available at https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/23870711/ftc-v-microsoft-preliminary-injunction-opinion.pdf.

[19] Lina M. Khan, Rohit Chopra, & Kelly Slaughter, Comm’rs, Fed. Trade Comm’n, Statement on the Withdrawal of the Vertical Merger Guidelines (Sep. 15, 2021) at 3, available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1596396/statement_of_chair_lina_m_khan_commissioner_rohit_chopra_and_commissioner_rebecca_kelly_slaughter_on.pdf.

[20] In this paper, the terms “hypermarket” and “supercenter” are used synonymously. See Richard Volpe, Annemarie Kuhns, & Ted Jaenicke, Store Formats and Patterns in Household Grocery Purchases, Economic Research Service, Economic Information Bulletin No. 167 (Mar. 2017), https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/82929/eib-167.pdf?v=0 (supercenters are also known as hypermarkets or superstores).

[21] Fed. Trade Comm’n, supra note 6.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Data obtained from: U.S. Census Bureau, Report on Retail Sales and Trends: Annual Retail Trade Survey: 2021, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/arts/annual-report.html.

[25] Id.

[26] FTC, supra note 6.

[27] Food Marketing Institute & The Hartman Group, Consumers’ Weekly Grocery Shopping Trips in the United States from 2006 to 2022 (Average Weekly Trips per Household), Statista (May 2022), available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/251728/weekly-number-of-us-grocery-shopping-trips-per-household.

[28] Kuhn, supra note 10.

[29] Id.

[30] Trip Drivers: Top Influencers Driving Shopper Traffic, Acosta (2017), available at https://acostastorage.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/prod/newsroom/publication_phetw_0rzq.pdf.

[31] Lijun Angelia Chen & Lisa House, US Food Shopper Trends in 2017, Univ. of Fla, IFAS Extension Pub. No. FE1126 (Dec. 7, 2022), https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FE1126.

[32] FTC, supra note 6.

[33] See Paul B. Ellickson, Paul L.E. Grieco, & Oleksii Khvastunov, Measuring Competition in Spatial Retail, 51 RAND J. Econ. 189 (2020) (“[C]lub stores are able to draw revenue from a significantly larger geographic area than traditional grocers. Hence, club stores are relevant substitutes for grocery stores, even if they are located even several miles away, a fact that could easily be overlooked in an analysis in which stores are simply clustered by geographic market.”).

[34] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Satellite Account to Measure the Retail Transformation: Organizational, Conceptual, and Data Foundations (2021), available at https://www.bls.gov/evaluation/a-satellite-account-to-measure-the-retail-transformation.pdf (“[T]he restructuring that started first with the warehouse clubs and superstores and then moved on to e-commerce has begun to blur the lines between the retail industry and several other sectors …”).

[35] Id. at 25 (“[C]hanges experienced by retail over the past few decades suggest that the sector is highly competitive and is undergoing substantial change and reorganization. As discussed earlier, the changes described involve warehouse clubs and superstores … e-commerce … digital goods, imports, and large firms …”).

[36] Paul B. Ellickson, Paul L.E. Grieco, & Oleksii Khvastunov, Measuring Competition in Spatial Retail, 51 RAND J. Econ. 189 (2020) (“Due to their size and attractiveness for larger purchases, club stores represent strong competitors to grocery stores even, when they are a significant distance away.”).

[37] Khan & Vaheesan, supra note 2, at 255 (“Grocers sought to bulk up in order to compete with the scale of warehouse clubs and large discount stores, fueling further mergers and leading many local grocers to close …”).

[38] FTC, supra note 6.

[39] Costco Wholesale Corporation, Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Aug. 28, 2022), https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/0000909832/000090983222000021/cost-20220828.htm; BJ’s Wholesale Club Holdings, Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Mar. 16, 2023), https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/1531152/000153115223000026/bj-20230128.htm; Walmart Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Mar. 27, 2023), https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/104169/000010416923000020/wmt-20230131.htm.

[40] Hean Tat Keh & Elain Shieh, Online Grocery Retailing: Success Factors and Potential Pitfalls, 44 Bus. Horizons 73 (Jul.-Aug., 2001); Appinio & Spryker, Share of Consumers Purchasing Groceries Online in the United States in 2022, by Channel, Statista (Sep. 2002).

[41] Navigating the Market Headwinds: The State of Grocery Retail 2022, McKinsey & Co. (May 2022), available at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/how%20we%20help%20clients/the%20state%20of%20grocery%20retail%202022%20north%20america/mck_state%20of%20grocery%20na_fullreport_v9.pdf.

[42] Id.; Dimitri Dimitropoulos, Renée M. Duplantis, & Loren K. Smith, Trends in Consumer Shopping Behavior and Their Implications for Retail Grocery Merger Reviews, CPI Antitrust Chron. (Dec. 2021), available at https://www.brattle.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Trends-in-Consumer-Shopping-Behavior-and-their-Implications-for-Retail-Grocery-Merger-Review.pdf.

[43] Dimitropoulos, et al., supra note (“Of course, adjustments to geographic market definition likely would need to be factored into the analysis, as club stores tend to have larger catchment areas than traditional grocery stores, and online delivery can reach as far away as can be travelled by truck from a central fulfilment center.”)

[44] U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, supra note 4 at 25-7.

[45] Maeve Sheehey & Dan Papscun, Kroger-Albertsons Merger Tests FTC’s Focus on Labor Competition, Bloomberg Law (Dec. 2, 2022) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/antitrust/kroger-albertsons-merger-tests-ftcs-focus-on-labor-competition.

[46] Kroger Union, UFCW, https://www.ufcw.org/actions/campaign/kroger-union (last accessed Jul. 26, 2023).

[47] Albertsons and Safeway Union, UFCW, https://www.ufcw.org/actions/campaign/albertsons-and-safeway-union (last accessed Jul. 26, 2023).

[48] Press Release, America’s Largest Union of Essential Grocery Workers Announces Opposition to Kroger and Albertsons Merger, UFCW (May 5, 2023), https://www.ufcw.org/press-releases/americas-largest-union-of-essential-grocery-workers-announces-opposition-to-kroger-and-albertsons-merger.

[49] Id. (“Given the lack of transparency and the impact a merger between two of the largest supermarket companies could have on essential workers – and the communities and customers they serve – the UFCW stands united in its opposition to the proposed Kroger and Albertsons merger”).

[50] Press Release, Kroger and Albertsons Companies Announce Definitive Merger Agreement, Kroger (Oct. 14, 2022), https://ir.kroger.com/CorporateProfile/press-releases/press-release/2022/Kroger-and-Albertsons-Companies-Announce-Definitive-Merger-Agreement/default.aspx.

[51] Ben Zipperer, Kroger-Albertsons Merger Will Harm Grocery Store Worker Wages, Economic Policy Institute (May 1, 2023), https://www.epi.org/publication/kroger-albertsons-merger.

[52] Nathan Miller et al., On the Misuse of Regressions of Price on the HHI in Merger Review, 10 J. Antitrust Enforcement 248 (2022), available at http://www.nathanhmiller.org/hhiregs.pdf.

[53] Press Release, The Kroger Family of Companies Provides New Career Opportunities to 100,000 Workers, Kroger (May 14, 2020), https://ir.kroger.com/CorporateProfile/press-releases/press-release/2020/The-Kroger-Family-of-Companies-Provides-New-Career-Opportunities-to-100000-Workers/default.aspx.

[54] Kevin Murphy, Transcript of Proceedings at the Public Workshop Held by the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice (Sep. 23, 2019), at 19, available at https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1209071/download.

[55] Roman Inderst & Tommaso M. Valletti, Buyer Power and the ‘Waterbed Effect’, CEIS Research Paper 107 (Feb. 21, 2014), at 2, https://ssrn.com/abstract=1113318.

[56] Albert Foer, Mr. Magoo Visits Wal-Mart: Finding the Right Lens for Antitrust, American Antitrust Institute Working Paper No. 06-07, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1103609.

[57] Michael Needler Jr., Senate Hearing on Kroger and Albertsons Grocery Store Chains, at 1:43:00, available at https://www.c-span.org/video/?524439-1/senate-hearing-kroger-albertsons-grocery-store-chains.

[58] Julie Creswell, Kroger-Albertsons Merger Faces Long Road Before Approval, New York Times (Jan. 23, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/23/business/kroger-albertsons-merger.html.

[59] Diana Moss, The American Antitrust Institute to the Honorable Lina M. Khan, American Antitrust Institute (Feb. 7, 2023), available at https://www.antitrustinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Kroger-Albertsons_Ltr-to-FTC_2.7.23.pdf.

[60] For an explicit economic model of the waterbed effect, see Roman Inderst & Tommaso M. Valletti, Buyer Power and the ‘Waterbed Effect’ 59 J. Ind. Econ. 1 (2011).

[61] DeHoog v. Anheuser-Busch InBev, SA/NV, No. 1:15-CV-02250-CL, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 137759, at *13-16 (D. Or. July 22, 2016).

[62] Safeway Merger Report, UK Competition Commission (2003), available at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20120119163858/http:/www.competition-commission.org.uk/inquiries/completed/2003/safeway/index.htm (“Overall, therefore, there is little evidence of an immediate or short-term ‘waterbed’ effect. … [O]ur surveys produced insufficient evidence on this point for us to conclude that any waterbed effect would be exacerbated by any of the mergers.”); Anticipated Merger between J Sainsbury PLC and ASDA Group Ltd: Summary of Final Report, UK Competition & Markets Authority (Apr. 25, 2019), available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5cc1434ee5274a467a8dd482/Executive_summary.pdf (“Overall, it seems unlikely that many retailers will raise their prices in response to the Merger; and even if some individual retailers do, the overall effect on UK households is unlikely to be negative. On that basis, our finding is that the Merger is unlikely to lead to customer harm through a waterbed effect.”).

[63] Supra note 6.

[64] See Dimitropoulos, et al., supra note 42.

[65] Id.

[66] Supra note 6.

[67] Publix, Facts and Figures (2023), https://corporate.publix.com/about-publix/company-overview/facts-figures.

[68] Caroline A., The History of Publix: Entering New States, The Publix Checkout (Jan. 4, 2018), https://blog.publix.com/publix/the-history-of-publix-entering-new-states; Press Release, Publix Breaks Ground on First Kentucky Store and Announces Third Location, Publix (Jun. 23, 2022), https://corporate.publix.com/newsroom/news-stories/publix-breaks-ground-on-first-kentucky-store-and-announces-third-location.

[69] Weis Markets, LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/weis-markets/about, (last accessed Jul. 26, 2023).

[70] Sam Silverstein, Weis Markets Unveils $150M Expansion and Upgrade Plan, Grocery Dive (May 2, 2022), https://www.grocerydive.com/news/weis-markets-unveils-150m-expansion-and-upgrade-plan/623015.

[71] Russell Redman, Wegmans lines up its next new store locations, Winsight Grocery Business (Dec. 1, 2022) https://www.winsightgrocerybusiness.com/retailers/wegmans-lines-its-next-new-store-locations.

[72] Dayen, supra note 3. (“As the Haggen affair makes clear, the whole idea of using conditions to allow high-level mergers and competition simultaneously has been a failure.”)

[73] Supra note 7.

[74] Id.

[75] Christopher A. Wetzel, Strict(er) Scrutiny: The Impact of Failed Divestitures on U.S. Merger Remedies, 64 Antitrust Bull. 341 (2019).