Should you know what you don’t know about Information Economics?

ICLE’s invitation-only Big Ideas Workshop series brings together early- and mid-career scholars to discuss important ideas in law & economics. This workshop explored some of . . .

What are you looking for?

ICLE’s invitation-only Big Ideas Workshop series brings together early- and mid-career scholars to discuss important ideas in law & economics. This workshop explored some of . . .

In March 2023, the Commission announced new guidelines on exclusionary abuses and amended its 2008 Guidance on enforcement priorities concerning exclusionary abuses. According to the . . .

Bloomberg Law – ICLE President Geoffrey Manne quoted in a Bloomberg Law story about the striking Hollywood guilds asking the Federal Trade Commission to investigate consolidation . . .

Bloomberg Law – ICLE President Geoffrey Manne quoted in a Bloomberg Law story about the striking Hollywood guilds asking the Federal Trade Commission to investigate consolidation among the Hollywood studios. You can read full piece here.

But the issues with the “feedback loop” are inherent to the new paradigm of streaming and have nothing to do with concentration, said Geoffrey Manne, the president of the nonprofit research group International Center for Law and Economics.

“It’s just that there is no good data anymore,” Manne said. Streaming services are struggling to determine how much their profits—mostly generated via subscribers—are attributable to any given TV show, he said.

“It’s not because the companies are trying to take advantage of anyone,” Manne said. “They may also be doing that, but that’s the Occam’s razor”—the simplest—assessment.

… Regardless of future FTC investigations, Manne predicted, the knowledge that Khan has taken a personal interest in the strikes will have a deterrent effect on industry mergers.

“It’s impossible to think that if any studios are planning a merger, they’re going through it with same assessment of potential risk they were before,” Manne said. “At the margin, some mergers that were being contemplated might be affected by this tension.”

Axios – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was quoted in a story in Axios about private-equity firm Roark Capital’s proposed acquisition of the Subway chain of . . .

Axios – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was quoted in a story in Axios about private-equity firm Roark Capital’s proposed acquisition of the Subway chain of restaurants. You can read full piece here.

One question is if Roark will have too much power over vendors who service restaurants, says Brian Albrecht, chief economist at the International Center for Law & Economics.

Clarion-Ledger – ICLE Academic Affiliate Joshua R. Hendrickson was quoted by the Clarion-Ledger in a story about a recent survey finding that the Mississippi cities of . . .

Clarion-Ledger – ICLE Academic Affiliate Joshua R. Hendrickson was quoted by the Clarion-Ledger in a story about a recent survey finding that the Mississippi cities of Jackson and Hattiesburg are among the places where the cost of living has risen the most in the past year. You can read full piece here.

However, University of Mississippi’s Chair of the Department of Economics Joshua Hendrickson said there must be more than meets the eye.

“These cost-of-living changes are largely driven by inflation. The variation by location is typically determined by local conditions,” Hendrickson said. “However, with regard to Jackson, there does not appear to be a particular component that is driving the cost-of-living higher.”

… “What is likely going on here is that places like Jackson and Hattiesburg have a lower cost-of-living than the average city in the U.S.,” Hendrickson said. “When there is significant inflation, many prices of goods and services rise uniformly across geographic locations. These result in higher percentage increases in lower cost-of-living areas. This seems to be the case here since 13 of the 15 cities listed began below the national average.”

Hendrickson pointed to several statistics in regard to Jackson, Hattiesburg and Mississippi in general.

Medium – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht and Academic Affiliate Thom Lambert were cited by Adam Kovacevich in a story published by Medium about the role . . .

Medium – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht and Academic Affiliate Thom Lambert were cited by Adam Kovacevich in a story published by Medium about the role of self-preferencing in the U.S. Justice Department’s upcoming Google case. You can read full piece here.

As Brian Albrecht noted:

In the case of retail trade promotions, a promotional space given to Coca-Cola makes it marginally easier for consumers to pick Coke, and therefore some consumers will switch from Pepsi to Coke. But it does not reduce any consumer’s choice. The store will still have both items.

…In other words, regulators or courts banning search default deals or slotting fees would likely only reaffirm the market-leading position of both Google and Oreos — but result in decreased revenue for the access points, Mozilla and Kroger. Or as Thom Lambert put it:

“The government’s success in its challenge to Google’s Apple payments would benefit Google at the expense of consumers: Google would almost certainly remain the default search engine on Apple products, as it is most preferred by consumers and no rival could pay to dislodge it; Google would not have to pay a penny to retain its default status; and Apple would lose revenues that it likely passes along to consumers in the form of lower prices.”

DOJ is likely to argue, as Lambert previewed, that Google’s deals give it higher search volume, which creates a “data barrier to entry” for Bing and DuckDuckGo — they don’t have enough scale to compete. As Lambert notes:

“In the government’s view, Google is legally obligated to forego opportunities to make its own product better so as to give its rivals a chance to improve their own offerings.”

But, he continues:

“This is inconsistent with U.S. antitrust law. Just as firms are not required to hold their prices high to create a price umbrella for their less efficient rivals, they need not refrain from efforts to improve the quality of their own offerings so as to give their rivals a foothold.”

…As Brian Albrecht put it:

Despite all the bells and whistles of the Google case…from an economic point of view, the contracts that Google signed are just trade promotions. No more, no less. And trade promotions are well-established as part of a competitive process that ultimately helps consumers.

Yahoo Finance – ICLE Senior Scholar Eric Fruits was quoted by Yahoo Finance in a story about the benefits of allowing supermarkets Kroger and Albertsons to . . .

Yahoo Finance – ICLE Senior Scholar Eric Fruits was quoted by Yahoo Finance in a story about the benefits of allowing supermarkets Kroger and Albertsons to merge. You can read full piece here.

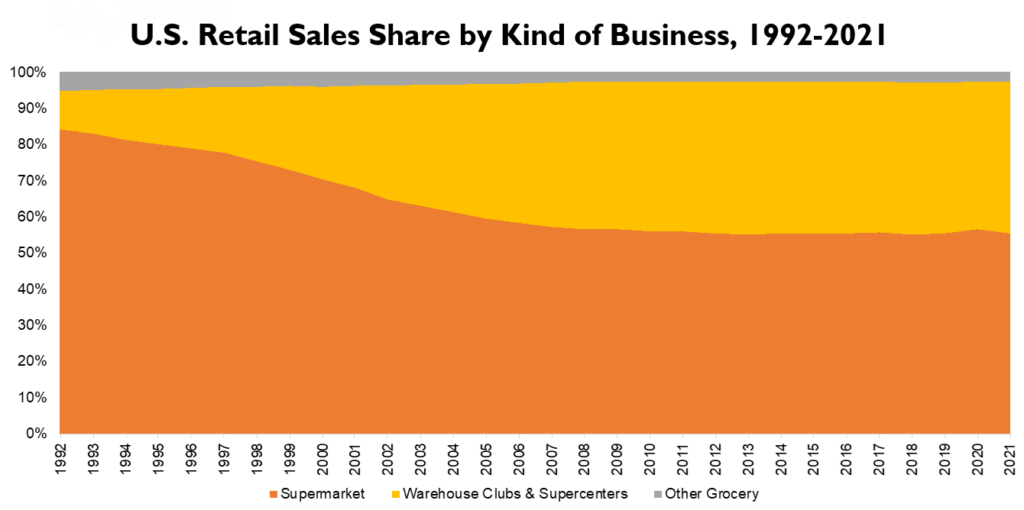

Growth of supercenters like Walmart, along with club stores like BJ’s (BJ) and Costco (COST), could be the biggest “long-run story” in the food and grocery industry, Eric Fruits, senior scholar at the International Center for Law & Economics, told Yahoo Finance. Fruits also highlighted Amazon’s (AMZN) purchase of Whole Foods for $13.7 billion as another deal that further intensified competition within the industry.

Reason – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was cited in a story in Reason about the Biden administration’s attempts to shift the standards of antitrust law. . . .

Reason – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was cited in a story in Reason about the Biden administration’s attempts to shift the standards of antitrust law. You can read full piece here.

Consumer welfare should be the sole standard for antitrust law. Economist Brian Albrecht wrote in National Review last December about the shift from the “Government always wins” antitrust standard that was successfully pushed by progressives until abandoned in the late 1970s. An emphasis on tangible economic reasoning allowed a consistent framework to take shape, including “the elevation of consumer welfare as antitrust regulation’s fundamental concern.” Chair Khan is trying to turn back the clock to a standard that will again allow the FTC and DOJ to always win.

KOIN – ICLE Senior Scholar Eric Fruits was quoted by Portland, Oregon television station KOIN in a story about the merger of Oregon Health & Science . . .

KOIN – ICLE Senior Scholar Eric Fruits was quoted by Portland, Oregon television station KOIN in a story about the merger of Oregon Health & Science University and Legacy Health. You can read full piece here.

“This is certainly something that the feds are going to look at if they are going to do a merger review between OHSU and Legacy. They may even mandate that Legacy or OHSU don’t close any facilities or do better on price transparency,” said Eric Fruits, from the International Center for Law & Economics in Portland.

…“There should be some scrutiny about whether a merger such as this might exacerbate some of those issues such as higher prices or reduced services,” said Fruits.

City Journal – ICLE President Geoffrey Manne and Director of Law & Economics Programs Gus Hurwitz were cited in a post at City Journal about the . . .

City Journal – ICLE President Geoffrey Manne and Director of Law & Economics Programs Gus Hurwitz were cited in a post at City Journal about the Federal Trade Commission and U.S. Justice Department’s recently unveiled draft merger guidelines. You can read full piece here.

The FTC has had a busy summer. It proposed severe new disclosure requirements for parties seeking to merge. Joining forces with the Justice Department, it moved to de-modernize the government’s merger guidelines. (“Weighted by the number of citations,” observe Gus Hurwitz and Geoff Manne, “the average year of the 50 cases the FTC and Justice Department cite in support of their approach is 1975—ages ago in antitrust law.”) The agency launched an investigation of OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT, and signaled its intent to regulate artificial intelligence more broadly. It accused Amazon of using so-called dark patterns to trick users into subscribing to Amazon Prime. (It also claims that Prime is too hard to quit. Never mind that one can do so in fewer clicks than it takes to file a comment with the FTC.) And any day now, Khan is expected to file her biggest lawsuit of all: her long-planned quest to break up Amazon.

WCPO – ICLE Senior Scholar Eric Fruits was quoted by Cincinnati television station WCPO in a story about a petition from several state attorneys general asking . . .

WCPO – ICLE Senior Scholar Eric Fruits was quoted by Cincinnati television station WCPO in a story about a petition from several state attorneys general asking the Federal Trade Commission to challenge to the merger of Kroger and Albertsons. You can read full piece here.

Kroger has a 75% chance of completing the proposed merger, but it might have to fight the FTC in court to get the deal done, said Eric Fruits, an antitrust expert and senior scholar for the International Center for Law & Economics in Portland Oregon.

“For the past 25-30 years, almost every single grocery merger has been allowed to go through with these spinoffs, or what are known as divestitures,” said Fruits, a Sycamore High School graduate who recently co-authored a detailed analysis of the likely legal arguments in the case. “My guess is that’s what Kroger and Albertsons are going to offer. The real question is whether or not the Federal Trade Commission will take that offer. And if they don’t, they could go to court and the judge could say, ‘This seems like a reasonable remedy. We’ll let you spin off the stores.’”

When Kroger announced the planned merger last October, it said it hoped to complete the deal by early next year. Fruits doesn’t think that can happen if the case goes to court.

“I would think that there’s bigger fish to fry than the Kroger-Albertsons merger,” said Fruits. “But you just don’t know what sort of political pressure these federal trade commissioners are under to try to show that they’re doing something big. And this is something big that they can try to block.”

ABC News – ICLE Academic Affiliate James Huffman was quoted by the ABC News in a story about the latest developments in a lawsuit by young . . .

ABC News – ICLE Academic Affiliate James Huffman was quoted by the ABC News in a story about the latest developments in a lawsuit by young plaintiffs who seek to overturn a Montana law that prohibits the consideration of greenhouse-gas emissions in evaluating whether to grant permits. You can read full piece here.

“The ruling really provides nothing beyond emotional support for the many cases seeking to establish a public trust right, human right or a federal constitutional right” to a healthy environment, said James Huffman, dean emeritus at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland.

CoStar – ICLE Editor-in-Chief R.J. Lehmann was quoted by CoStar in a story about the impact of recent spates of natural disasters on the insurance market . . .

CoStar – ICLE Editor-in-Chief R.J. Lehmann was quoted by CoStar in a story about the impact of recent spates of natural disasters on the insurance market for commercial properties. You can read full piece here.

“It’s raised alarms for the insurance industry and property owners because now people are thinking about the effects of things like rising ocean levels and the effects that saltwater exposure can have on some of these older properties,” said Ray Lehmann, a Miami-based senior fellow with the International Center for Law & Economics, a nonpartisan and nonprofit research organization that tracks issues including business risks associated with climate change.

Lehmann told CoStar News that commercial property insurers in California generally have more leeway to negotiate pricing with customers than exists in other states, including Florida. But those insurers’ rising costs for their own reinsurance are making it difficult to earn profits from policies without being able to pass on those costs to California commercial customers in the face of escalating wildfire, flooding and other risks.

Lehmann said those risks are also making it difficult for insurers to profit from previously lucrative, high-end commercial and residential policies that were offered for many years in California hubs of the wealthy, like Malibu and Santa Barbara, now increasingly prone to fires and other damaging weather events.

Cowboy State Daily – ICLE Academic Affiliate George Mocsary was quoted by Cowboy State Daily in a story about a U.S. Supreme Court’s order allowing the . . .

Cowboy State Daily – ICLE Academic Affiliate George Mocsary was quoted by Cowboy State Daily in a story about a U.S. Supreme Court’s order allowing the Biden administration’s regulation of so-called “ghost guns” to remain in force while legal challenges play out. You can read full piece here.

The term “ghost guns” is “kind of silly name. It tends to illicit an emotional reaction rather than an intellectual one,” University of Wyoming law professor George Mocsary, director of UW’s Firearms Research Center.

The Biden administration and others have made “ghost guns” out to be a serious problem because they are supposedly fueling a wave of armed crime with untraceable weapons.

That’s simply not the case, Mocsary said.

“Criminals are not making their own firearms. The equipment to make your own firearm at home isn’t just a small piece of equipment,” he said. “The entire ‘ghost gun’ regulation is just a lot of noise to get attention. The number of those firearms used in crime is miniscule compared to the number of regular firearms used in crimes.”

Axios – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was quoted in a story in Axios about the pending merger between supermarkets Kroger and Albertsons. You can read . . .

Axios – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was quoted in a story in Axios about the pending merger between supermarkets Kroger and Albertsons. You can read full piece here.

In court, it’s likely to be a “bread-and-butter” argument over market definition, market share nationally and in local markets, and which companies are considered competitors, says Brian Albrecht, chief economist at the International Center for Law & Economics.

…But there’s a good argument that wholesale clubs like Costco, which have been excluded in the past, and Amazon, which operates both online and increasingly physical stores, should also be included as rivals, says Albrecht.

He says that stores located farther away that can now deliver via online-delivery platforms such as Instacart could be added to the list.

Whether Dollar Stores should be included is debatable, Albrecht says.

Townhall – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was cited in an op-ed in Townhall about the new merger guidelines. You can read full piece here. The . . .

Townhall – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was cited in an op-ed in Townhall about the new merger guidelines. You can read full piece here.

The DOJ and FTC are unequivocally trying to prevent mergers, lowering the bar for what is considered presumptively illegal. The guidelines redefine thresholds, classifying more markets as concentrated while also stating that a market share of over 30 percent presents a threat of undue concentration. The goal, according to economist Brian Albrecht, is to “stop more mergers of every kind without regard for economic argument or recent law.”

Axios – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was quoted in a story in Axios in a story about the Federal Trade Commission’s emerging approach to mergers. . . .

Axios – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was quoted in a story in Axios in a story about the Federal Trade Commission’s emerging approach to mergers. You can read full piece here.

Brian Albrecht, chief economist at the International Center for Law & Economics, predicts the FTC will challenge the deal in court, but it will be approved based on precedents.

- Precedents suggest the transaction would be assessed through the lens of traditional market definitions, competition within local markets, and which retailers are or are not considered competitors.

Between the lines: While industry watchers like Albrecht predict the transaction gets completed, the source close to the FTC says that view disregards considerations like protecting small businesses.

The Dispatch – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was cited by The Dispatch in a story about the Federal Trade Commission and U.S. Justice Department’s new . . .

The Dispatch – ICLE Chief Economist Brian Albrecht was cited by The Dispatch in a story about the Federal Trade Commission and U.S. Justice Department’s new draft merger guidelines. You can read full piece here.

Earlier this year, for example, Albrecht and his colleagues at the International Center for Law and Economics wrote a terrific report documenting some of the biggest “doomsday mergers” that fizzled out – or, like beer industry consolidation, actually improved the market’s competitiveness and consumer surplus – in retrospect. This includes Amazon/Whole Foods, Bayer/Monsanto, Google/Fitbit, Facebook/Instagram/Whatsapp, and Ticketmaster/Live Nation. In each case, antitrust hawks wrongly predicted competitive destruction (e.g., Amazon/Whole Foods) or ignored the merger at the time it occurred and only claimed it was an obvious problem years later (e.g., Facebook/Instagram).

Arizona Republic – A recent ICLE issue brief on the proposed merger between Kroger and Albertsons was cited by the Arizona Republic. You can read full . . .

Arizona Republic – A recent ICLE issue brief on the proposed merger between Kroger and Albertsons was cited by the Arizona Republic. You can read full piece here.

The issue of divesting stores could emerge as a key negotiation point in any legal settlement or agreement with regulators, and this could be a relatively easy issue to resolve, according to a recent analysis of the merger by the nonpartisan International Center for Law & Economics.

…“The upshot is the food and grocery industry is arguably as competitive as it has ever been,” said the report on the merger, written by Brian Albrecht and three other analysts at the International Center for Law and Economics.

…If anything, raising prices would make Kroger and Albertsons stores less appealing against low-cost rivals. The proliferation of wholesale clubs, e-commerce options and other competition “significantly constrains” the supermarkets’ ability to raise prices, argued the report from the International Center for Law & Economics.

…State attorneys general can enforce many federal antitrust laws, and they often sign onto federal lawsuits filed by the the FTC or Justice Department, said Brian Albrecht, one of the authors of the International Center for Law & Economics report.

He predicts the FTC will bring a case and some state AGs will get behind it.

“The FTC will do the heavy lifting on everything, but the AGs can go back to their voters and say they are doing something,” Albrecht said in an email to the Arizona Republic.

Executive Summary Electronic peer-to-peer (P2P) payments can serve as an effective alternative to other payment methods, such as cash and checks. Real-time payments (RTPs)—originally developed . . .

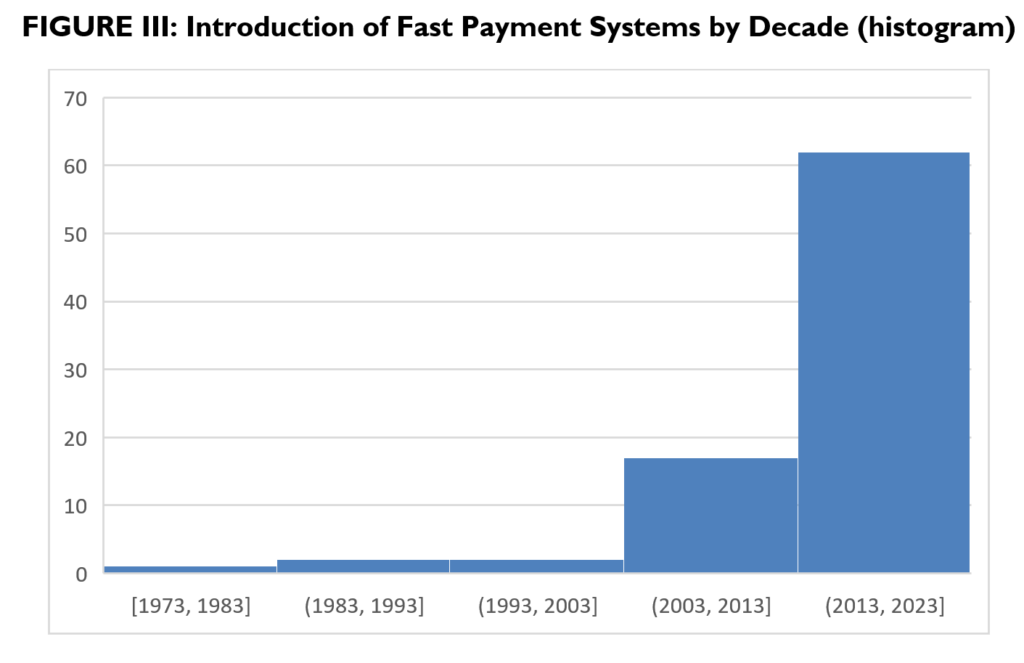

Electronic peer-to-peer (P2P) payments can serve as an effective alternative to other payment methods, such as cash and checks. Real-time payments (RTPs)—originally developed to reduce settlement times and thereby lower float costs—have come into their own as means to facilitate interoperability between otherwise-closed P2P payments systems. That likely explains why 62 new RTP systems were created in the past decade, compared with a total of 22 in the prior four decades.

P2P payments and associated RTP rails are well-suited for payments where immediacy and finality are required, where the goods or services have already been delivered or are being supplied by a trusted provider, and where the payor is satisfied that the warranties provided by the payee are adequate and easily enforced. For such transactions, P2P payments are in many ways superior to cash, checks, or older EFT-based online debit transactions.

By contrast, P2P payments in general—including those made over RTP rails—are poorly suited to transactions where immediacy and/or finality are not required and where there are significant risks of nonperformance by the payee. This is because the speed and finality of P2P payments made over RTP rails makes it more difficult to detect, prevent, and rectify fraud, theft, and mistake. P2P-RTPs are thus particularly poorly suited to transactions where goods and services are delivered after payment has been sent and the payor does not have an established trust relationship with the merchant. In such circumstances, closed-loop or dual-message open-loop payment cards will typically be superior.

Organizations designing and implementing P2Ps and RTPs would do well to bear these lessons in mind and not pursue overly ambitious and impractical goals. Where those organizations are governmental entities—such as central banks—that have a remit to regulate payments, it is essential that they implement measures to mitigate potential conflicts of interest.

This is the first in a series of ICLE issue briefs that will investigate innovations in and the regulation of payments technologies, with a particular focus on their effects on financial inclusion. The aim of this paper is to offer an overview of two important and related payment systems: peer-to-peer (P2P) and real-time payments (RTPs).[1] Subsequent papers in the series will look at specific aspects of these systems in greater detail.

In traditional payment systems, funds sent from one account to another can take from hours to days to clear and settle. These delays have an opportunity cost: once funds have been debited from a sender’s account, they are not available for use until they are credited at the recipient’s account. In addition, delays in clearing and settlement can contribute to counterparty risk for recipients. At the same time, there are tradeoffs between the speed and finality of payments and counterparty risk for senders.

In principle, P2P and RTPs hold significant potential to increase financial inclusion and enhance economic efficiency. But to do so successfully, such tradeoffs must be acknowledged and factored into system designs. Relatedly, it is important for system designers and regulators to understand both the likely use cases for P2P and RTP systems and the uses to which they are poorly suited. For example, some P2P and RTP evangelists have argued that they will replace credit cards.[2] As explored below, this seems unlikely for two reasons: first, credit cards have more effective mechanisms to address counterparty risk for consumers and, second, in many cases, credit cards better enable consumers to address timing mismatches between income and consumption.

P2Ps and RTPs come in various guises. Some are purely private systems, including P2Ps offered by Venmo, Zelle, and PayPal, and RTPs operated by The Clearing House, Visa, Mastercard, and PayUK. Some RTPs (such as India’s Unified Payments Interface, or UPI) are public-private partnerships. Other RTPs—such as Brazil’s Pix and the forthcoming FedNow system in the United States—are run by central banks. These various systems have adopted different approaches to implementation. By considering the particular system designs and the consequences of those differences, this paper offers tentative best practices for P2P and RTP design. Future papers will explore these issues in greater detail.

In order to put P2Ps and RTPs into the broader context of payment systems as they have evolved, Section II describes the means by which payments are cleared and settled, starting with an account of the basic process, followed by descriptions of some of the primary payment-settlement systems, including automated clearing houses, faster-payment systems, P2Ps, and RTPs. Section III considers the benefits and drawbacks to P2Ps and RTPs. Finally, Section IV offers concluding remarks.

Bank accounts are essentially ledgers that record credits and debits. When funds move from account A to account B, a debit is recorded on account A and a credit recorded in account B. This is typically a four-stage process: authorization, verification, clearing, and settlement:

Historically, this was primarily done through the use of checks and deposit slips. The signed check authorizes the transfer from the sender (debitor) account (A) and the deposit slip authorizes the receipt of funds by the creditor account (B). The bank—or banks, if the accounts are with different depository institutions—then verify the authenticity of the checks and deposit slips and clear the funds to be transferred. Finally, the bank(s) adjust the ledgers in each account, recording a debit in account A and a credit in account B.

Consider the simple case of a two-bank system with only one account holder in each bank. The owner of account A in bank X writes and signs a check to the owner of account B in bank Y authorizing the transfer of funds from A to B. In this case, X confirms the authenticity of the check signed by the owner of A and clears funds to be transferred to B. Meanwhile, settlement requires funds to be moved from X to Y, which entails the recording of a debit in X’s master ledger and a credit in Y’s master ledger. To avoid counterparty risk, while a debit will be recorded in A after clearing, a credit will only appear in B after settlement.

Now, consider the slightly more complicated case of multiple accountholders in each of the two banks. In this case, numerous accountholders in each bank write checks to account holders in the other bank. These checks are first cleared. Then, at the end of the day, the total amount of funds cleared between all accounts in X and Y would be calculated and any difference in the net amount would be settled by adjusting the ledgers of the two banks. As before, funds debited from senders’ accounts only appear as credits in recipients’ accounts following settlement.

In practice, there are many banks and many accountholders within each bank. On any day, some number of accountholders in each bank write checks to accountholders in other banks. It is therefore more efficient for clearing and settlement to occur on a multiparty basis. This led to the establishment of clearing houses, which are independent intermediaries that facilitate clearing and settlement. In 1863, the largest U.S. banks formed The Clearing House (TCH) for this purpose. The process is still essentially the same, however, with settlement occurring following the netting of amounts owed between each bank in the system.

Electronic payments enable more rapid funds transfer. The earliest such payments were “wires,” which began in the 19th century, with information about the sender and recipient being sent between individual banks over telegraph wires. In 1970, TCH established the Clearing House Interbank Payment Services (CHIPS) to clear and settle wire payments for eight of its largest members. Membership was subsequently expanded to banks across the United States and internationally.

During the 1950s and 1960s, banks introduced computers and gradually shifted from paper-based ledgers to electronic ledgers. As the cost of computers and telecommunications fell, it became increasingly efficient to send information relating to smaller-value payments electronically, which in turn facilitated automation of the entire payments system. In 1968, UK banks introduced the first automated electronic clearing house, called Bankers’ Automated Clearing System (BACS).[4] In 1972, a group of California banks established the first automated clearing-house (ACH) network in the United States to clear and settle accounts electronically.[5] Other regional networks and the Federal Reserve (FedACH) followed and, in 1974, these networks established the National Automated Clearing House Association (NACHA). Similar networks were developed in many other countries, typically supported by—and, in many cases, run by—central banks.

In the United States, settlement over NACHA and CHIPS originally took two to three days.[6] Settlement on payment systems in other jurisdictions, such as BACS in the United Kingdom, typically occurred on similar timeframes.[7] Over time, settlement times for payment systems have gradually been reduced. Most U.S. settlements now take only a day or less. Since 2010, FedACH has offered a same-day clearing/settlement service,[8] while NACHA has offered a similar same-day clearing/settlement service since 2016.[9] CHIPS settles at the end of the day over Fedwire.[10]

Separate from the ACH systems, real-time gross-settlement (RTGS) systems, such as Fedwire, are used for settling large-value payments between banks without netting. These typically settle immediately upon receipt, during hours of operation.[11] Because there is no netting, banks must either ensure they have sufficient reserves to send funds, or borrow funds to cover outgoing payments. Potential mismatches between outgoing and expected incoming funds can lead to cash hoarding, driving up demands for intraday borrowing, as occurred during the 2008 financial crisis.[12]

So-called “fast payments” or “faster payments” systems are RTGS systems designed to clear and settle smaller sums quickly between accounts. In general, such systems have the following features: (1) payment messages transmit and clear sufficiently quickly that payor and payee can see changes in their respective account balances more-or-less instantly (practically speaking, that means under a minute); (2) payment is final and irrevocable.[13]

In 1973, Japan introduced Zengin, the first nationwide fast-payments system, and many others have followed suit in the ensuing half-century.[14] An early driver of fast payments’ introduction of was the desire to reduce float (see Section III Part B below). More recently, interoperability among P2P payment networks has become a major driver, leading to the introduction of systems that operate continuously. Such round-the-clock fast-payment systems are typically referred to as real-time payments (RTPs). (Various other labels, including “instant payments,” are also used.)

With improvements in the speed and capacity of data processing and transfer, settlement times have gradually fallen. Indeed, some RTPs, such as TCH’s RTP, settle instantly. This requires payment service providers (PSPs) to maintain a balance with the settlement provider sufficient to “pre-fund” any payment (similar to RTGS). Indeed, some proponents of RTPs argue that instantaneous settlement is a defining feature of such systems.[15] Other fast-payment systems, such as the UK’s Faster Payments Service (FPS), continue to operate on a deferred-settlement basis but are nevertheless referred to as RTPs because the other criteria are met. For the purposes of this primer, a payment system is considered an RTP if transactions using the system:

As noted, one of the drivers leading to the introduction of RTPs has been peer-to-peer (P2P) payments. Most P2P payments systems began as closed systems. While transfers within these P2P systems would often occur in real time, transfers into and out of the system—including to other P2P systems—could take days. RTPs offer a solution to this problem, enabling interoperability among different P2P systems, as well as interoperability between traditional bank accounts and P2P systems.

The first electronic peer-to-peer (P2P) payment system was M-Pesa,[16] a pilot of which was established in Kenya in 2005 by Safaricom, a cellphone-service provider, and subsequently rolled out nationwide in 2007. M-Pesa was inspired by the sharing of air-time credits by cellphone users in various sub-Saharan African countries.[17] Realizing that such air-time credit sharing was effectively acting as a form of money transmission and had the potential to enhance financial inclusion and associated economic development, the UK Department for International Development provided a challenge grant to Vodafone to support the development of more formal systems.[18] Initially, Vodafone worked with its Kenyan affiliate, Safaricom, to offer subscribers the ability to purchase M-Pesa funds at registered retailers in exchange for cash, thereby effectively turning their cell phones into mobile wallets. Users could send funds to others via SMS. Over time, M-Pesa expanded into other markets[19] and built numerous service offerings, including online payments[20] and savings and loans.[21] It now enables funding of accounts via online bank debits.[22]

Numerous companies subsequently built wallet applications for smartphones that enable users to link their bank accounts. This allows them to add funds by debiting those accounts and to deposit funds by sending credit to their accounts. Users of these wallets can send funds directly to other users of the same wallet. Examples include Venmo, Zelle, PayPal, Google Pay, Apple Pay Cash, Cash App, Paytm (India), WhatsAppPay (currently in India and Brazil), ViberPay (currently in Greece and Germany), and China’s AliPay and WeChatPay.

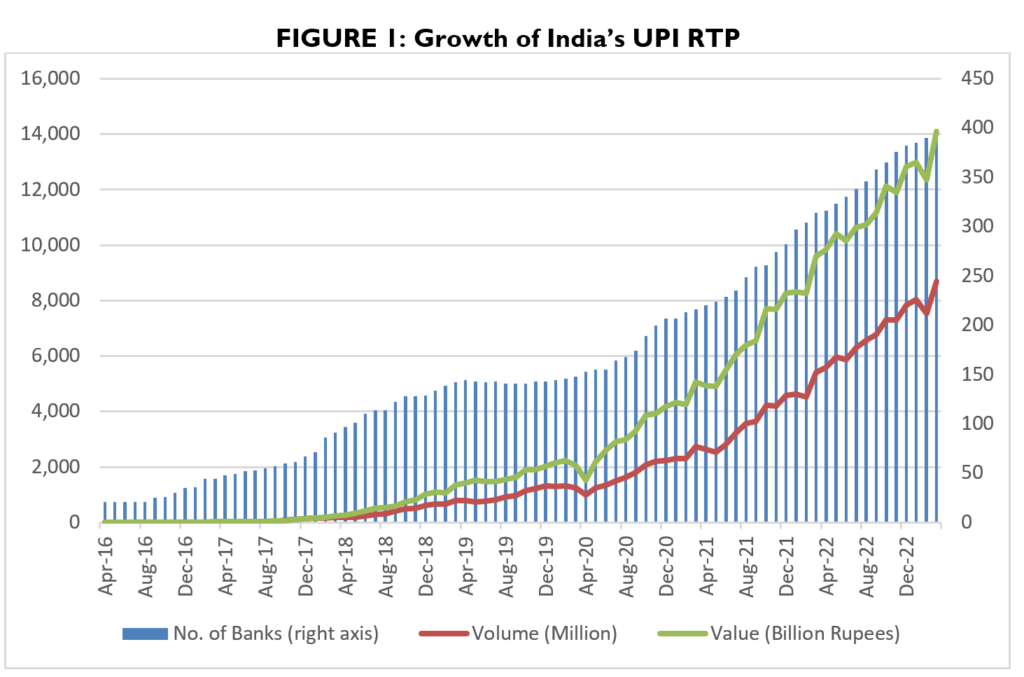

More recently, several bank associations and clearing houses have established RTP systems that facilitate interbank payments in real time, thereby in principle enabling interoperability between P2P systems. In some cases, interoperability has been baked in by design. For example, in 2016, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) created the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which is an RTP with an associated API that facilitates “push” credit payments and requests for payment for NPCI member banks.[23] As Figure I shows, around 400 banks are now part of UPI, which sees 8 billion monthly transactions with a total value of 14 trillion Rupees (about $170 billion).

SOURCE: NPCI[24]

SOURCE: NPCI[24]

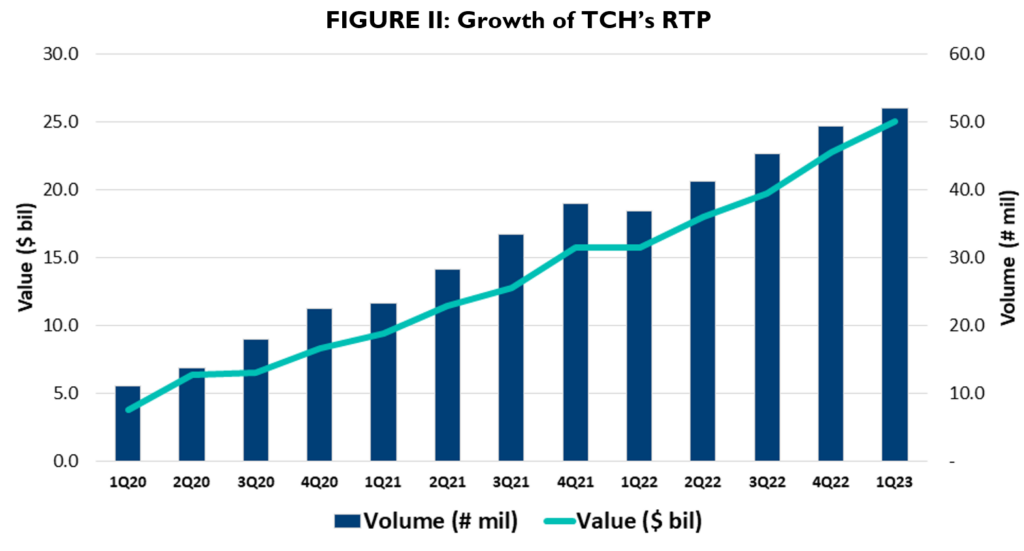

TCH introduced an RTP system for member banks in 2017.[25] As Figure II shows, the RTP has experienced explosive growth over the past three years and many U.S. P2P services now operate over it, effectively turning those P2Ps into RTPs.

In the first quarter of 2023 alone, TCH’s RTP facilitated 50 million transactions with a total value of about $25 billion. While P2Ps operating over TCH’s RTP are not necessarily interoperable, Zelle users can send funds directly to a counterparty’s bank account over RTP, even if that counterparty does not have Zelle installed at the time the payment is sent (they will have to install Zelle to be able to receive the funds).

SOURCE: TCH[26]

Central banks have also established and are establishing RTPs. Notable examples include Brazil’s Pix,[27] which was launched in 2020; the U.S. Federal Reserve’s FedNow, which launched in July 2023;[28] and Bank of Canada’s Real Time Rail.[29]

At the time of writing, fast payments systems have been introduced in 72 countries,[30] with several of those jurisdictions having more than one such system. As can be seen in Figure III, the vast majority of fast payment systems were introduced in the past decade; most of those are RTPs.

SOURCE: Based on information from ACI Worldwide[31]

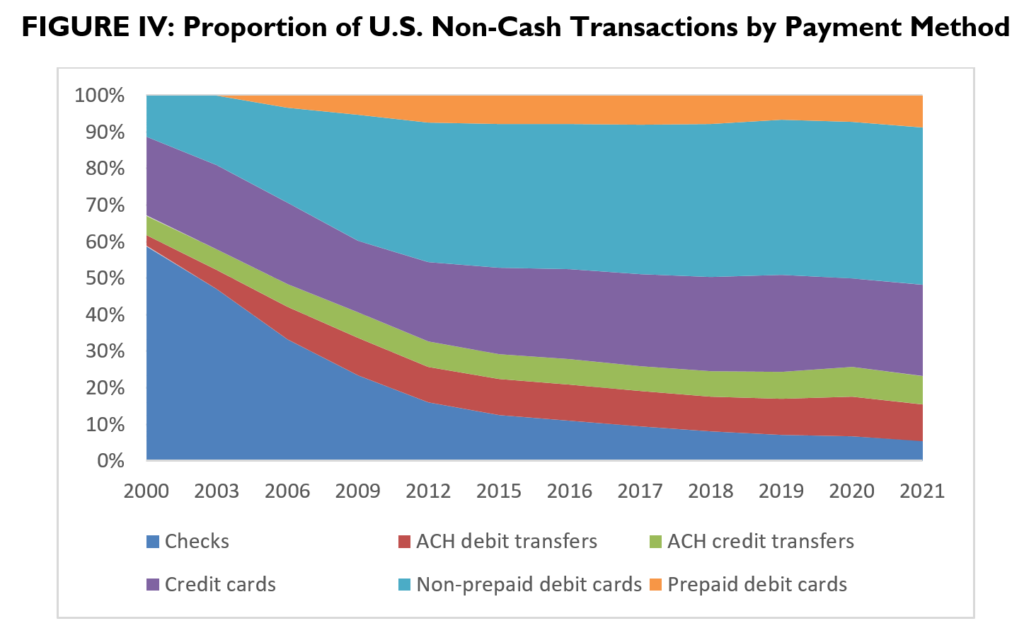

Payment-card networks emerged in the 1950s and have grown rapidly since, becoming the dominant means of retail payment in the United States and other OECD jurisdictions. Figure IV shows the dramatic increase in the proportion of U.S. transactions made using payment cards over the past two decades, which rose from 32% in 2000 to 77% in 2021.

The earliest payment cards—Diners Club and American Express—were and are still largely closed-loop systems, operating separately from bank networks. In the late 1950s, banks began operating their own payment-card networks. Over time, these bank-card networks gradually became more expansive and independent, with Visa and Mastercard becoming the largest such networks in the world, although there remain many competitors, including JCB, China Union Pay, and numerous national schemes.

Today, payment card systems can be divided into three main types:

SOURCE: Federal Reserve Payment Study[32]

As the name suggests, closed-loop cards, such as American Express and Discover, operate largely outside the banking system. When a payor uses a closed-loop card to make a purchase, the card issuer decides whether the payment is legitimate (for example, by authenticating the payor and undertaking fraud checks) and whether the payor has sufficient credit; if it passes those checks, the issuer guarantees to pay the payee.

When a payor uses a card operating over an open-loop dual-message (“signature”) payment network, two messages are sent. The first is a request for authorization sent to the issuing bank, which confirms the authenticity of the card and checks whether the cardholder has sufficient credit remaining (for a credit transaction) or funds in their account (for a debit transaction). But the message is also parsed by the network, which is able to monitor for fraud. If authorized, the second message contains information confirming the actual amount of the transaction, which is then either added to the cardholders’ credit-card bill or debited from the cardholder’s account during clearing and settlement, as appropriate.

In this sense, the dual-message settlement process is analogous to a check, in that there is some delay in the posting and clearing of the transaction. The ability to put a “hold” on a dual-message card payment enables merchants to delay payment (sometimes by as much as several days), thereby reducing the likelihood of fraud and associated chargebacks.[33]

Single-message debit networks generally rely on the personal identification number (PIN) programmed on the card to authenticate a transaction. As a result, the only message that is required is a notification to the issuing bank to debit the account of the cardholder in the amount they have authorized, and to credit that amount to the account of the merchant—less the discount fee, which is paid to the acquiring bank. Because of the nature of the transaction, settlement can be effected over banks’ electronic-funds-transfer (EFT) networks, which were initially built to settle transactions at shared ATMs, and subsequently over networks of ATMs.[34] As with an ATM transaction, single-message debit transactions settle and funds are transferred more or less immediately from the consumer’s account.

One of the major advantages of card payments has always been that merchants are guaranteed payment (on the condition that they comply with the payment-card rules). The closed-loop systems and dual-message open-loop systems are not RTPs, however, because they do not settle instantly. As discussed below, this has certain advantages. Open-loop single-message systems, by contrast, can and increasingly do operate over RTPs for debit payments. For example, Visa Now and Mastercard Send enable debit-card holders to make real-time payments.[35]

P2Ps and RTPs have some significant advantages over other payment systems. In particular, they can reduce counterparty risk for recipients, decrease opportunity costs of funds, and facilitate more advanced bilateral messaging between payor and payee. But they also have some drawbacks. Most notably, they entail high counterparty risk for payors; have engendered new types of fraud and theft risk; and lack any built-in credit facility. This section discusses these benefits (parts A, B, and C) and drawbacks (parts D, E, and F).

Transfers sent using a system that nets payments, such as ACH or BACS, take some time to settle. As such, use of these payment systems creates a risk for recipients that payments will not arrive. This is particularly problematic for large-value transactions, such as home purchases, and for retail payments where the purchaser takes possession of the goods before the payment settles.

One way to reduce such payee counterparty risk is to use escrow (whereby funds are held on trust by a third party until the transaction is completed), banker’s drafts (also known as teller’s checks), or same-day wires. But these are all relatively costly solutions and hence only viable for larger-value transactions, such as the purchase of a car or a house. Wire transfers are clearly not suitable for transactions where the goods or services are of relatively low value, especially in cases where the purchaser will have left the premises before the wire has arrived, which would typically be the case for retail sales.

In comparison to wires, banker’s drafts, and escrow, credit and debit cards offer a lower-cost solution to counterparty risk. In both cases, payment is effectively guaranteed by the issuer (if the merchant complies with the card-network rules). In order to be able to accept credit or debit cards, however, the payee must establish a merchant account with an acquiring bank. While the costs and difficulty of establishing such an account has fallen with the introduction of modern payment-processing technologies, it can still be a barrier for merchants selling relatively small amounts of lower-valued items and is unlikely to make sense for individuals who make only occasional sales.

In contrast to these other payment methods, RTPs essentially eliminate counterparty risk for payees through the simple expedient of finality. This means that payees can see that funds have arrived nearly the moment that they are sent and know that the payment cannot be reversed. Meanwhile, when associated with a P2P system, RTPs can have very low setup costs, making them attractive for individuals and low-volume merchants.

RTPs also eliminate the opportunity cost associated with funds that take time to settle. Compared with some other forms of payment—such as checks or credit cards, which can take a day or more to settle—the instantaneous settlement available with RTPs can create significant benefits for payees.

The Federal Reserve estimates that approximately 12 billion checks were written in 2021, with a total value of $27.47 trillion.[36] Of those, approximately 800 million, with a value of $240 billion, were converted to ACH. This means that the remainder—i.e., 11.2 billion checks, with a combined value of $27.23 trillion—were processed through conventional clearing. It typically takes about two business days for a check to clear and settle, which means that U.S. businesses require an additional gross daily “collection float” of about $210 billion to cover this lag between payment and settlement.[37] In practice, the net collection float required is far lower, because most checks are paid from one business to another; at any point in time, many businesses will be both debtors and creditors. Nonetheless, the need for even a few billion dollars of collection float is a significant cost, either reducing the amount of cash available for other uses or requiring lines of credit and associated interest payments. Using RTPs in place of checks can eliminate this float and associated costs.

Another advantage of RTPs is improved documentation and bilateral communications. Some RTPs have introduced enhanced bilateral messaging between payer and payee.[38] Among other things, this enables senders to verify the identity of the account to which they are sending funds, which can reduce the incidence of mistakes. In addition, payees can send requests for payment to payors, which can simplify the payment process (but as noted below, can lead to fraud). In addition, messages can include human-readable documents such as invoices and receipts that can improve reconciliation by both parties.

While counterparty risk for payees is low when using a RTP, the opposite is true for those who use RTPs to pay for goods and services—and for largely the same reason: the finality of payments made using an RTP means that, once a payment has been initiated, it cannot be stopped or reversed. This reduces counterparty risk for payees and increases it for payors. If the goods or services purchased using an RTP system are not supplied or do not meet the payor’s expectations, the payor cannot initiate a reversal or chargeback. (The payor could send a request-for-payment to the recipient, but the recipient is under no obligation to comply.)

Fraud and theft are perennial problems with payment systems of all kinds. Cash sales are particularly susceptible to “skimming,” whereby the till operator takes some of the cash tended (for example, by overcharging or by failing to ring up the correct amount in the register).[39] Cash is also susceptible to theft while in transit. To reduce such problems, merchants invest in such technologies as product bar codes, which prevent till operators from inputting incorrect prices (as well as improving inventory management) and security firms that use armored vehicles to transport cash.[40]

Non-cash payment methods are not subject to physical theft per se, but criminals have deployed all manner of schemes to use them to steal and defraud. Among other things, checks have been used to steal funds by impersonation of account holders; to defraud merchants by pretending to spend funds that are not available (“bouncing”); and to embezzle funds from companies. To address these problems, merchants introduced requirements like identity confirmation and caps on check amounts, while banks introduced card-based guarantees, and payor companies and banks introduced multi-signature requirements.[41]

Payment cards have suffered some similar problems. In response, issuing banks, merchants, card-payment networks, and other participants in the card-payments ecosystem have introduced rules and technologies designed to prevent fraud and theft. Early solutions included payment-authorization requirements; floor limits (above which authorization is required); and chargebacks (the ability to charge a transaction back to the merchant when an illegitimate transaction has not been authorized).[42] More recent innovations include machine-learning-based systems that monitor individual-payment patterns, with suspicious transactions subject to rejection or additional authorization requirements, as well as tokenized payments, which prevent the collection and transmission of personal account numbers (PANs).[43]

These rules and technologies have dramatically reduced fraud at the point of sale. But new technologies have created new opportunities for criminals to adapt old scams and develop new ones. The shift toward online transactions, for example, led to an explosion of card-not-present fraud.[44] As before, companies in the payment-network ecosystem have responded by developing systems that limit such fraud, such as the use of cookies, address verification, one-time passwords, velocity checks, multi-factor authentication, notification alerts, fraud scoring, and tokenization using token vaults.[45]

RTP systems are able to reduce some kinds of fraud and mistake. For example, the ability to check the identity of the recipient of the payee should, in principle, reduce the likelihood that a payment is sent to the wrong recipient. Raising the confidence of the payor, however, can also contribute to push-payment fraud. The lack of ability to reverse payments made over an RTP makes such systems particularly prone not only to push-payment fraud, but also to other kinds of frauds, as discussed in the subsections below.

One of the most common types of payment fraud is also one of the oldest. A fraudster pretends to offer goods or services (often apparently in the name of a real business) and asks for upfront payment, but never delivers the goods or services. Such cons can take many forms, but increasingly they use online communications (websites, emails, app-based systems) and take advantage of irrevocable electronic transfers of funds.

This is the essence of “authorized push payment” (APP) fraud, which involves a con artist sending a request for payment (RFP) from a fake business (usually with a name that is very similar to that of a real business). The victim, assuming the request is from a legitimate business, then authorizes payment. APP fraud has become particularly prevalent in the United Kingdom since the introduction of the country’s Faster Payment System (FPS) RTP.[46]

In some jurisdictions, the immediacy and finality of RTPs has been associated with an increase in other more disturbing crimes. Shortly after the introduction of Pix, Brazil saw a 40% rise in the phenomenon of “lightning kidnappings.” [47] Traditionally, such kidnappings involved victims being taken to an ATM and forced to take out money to secure their release. In the more recent iteration of the scheme, kidnappers simply demand that victims make a transfer to the kidnapper’s Pix account.

In response, Brazil’s central bank (BCB) capped the value of P2P Pix transactions made between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. to R1,000 ($182, at the time).[48] Meanwhile, some Brazilians have taken matters into their own hands, responding to the threat of Pix kidnappings by purchasing secondary “Pix phones.”[49] Users load these mid-range Android phones with banking and Pix apps and leave them at home. Meanwhile, they delete all banking apps from their primary phone. While such an approach allows those who can afford a second phone to prevent criminals from stealing potentially large amounts of money, it is quite a costly solution.

Brazil’s Pix also appears to be particularly susceptible to cybersecurity risks. Over the past 18 months, there have been three significant cybersecurity violations relating to Pix accounts. The first three were data breaches that appear to have arisen as a result of inadequate cybersecurity protections at banks and fintech companies whose account holders had the Pix app installed.[50] One concern is that criminals may be seeking to use data gathered from these account breaches to create fake accounts in the names of real people, which they could then use to receive funds from the hostages they kidnap and/or engage in other criminal activities. They could then launder the money by using Pix to buy goods and, after depleting the account, destroy the phone used to create it.

The fourth breach, identified in late 2022, is by far the largest and potentially most serious, as it involved the use of a piece of malware nicknamed PixPirate, which targets Android versions of the Pix app itself and potentially affects all Pix customers using Android phones.[51] It would appear that PixPirate enables the theft of passwords used to access bank accounts, as well as the interception of SMS messages. In combination, these data could be used to defeat some types of two-factor authentication.

In some respects, the problems of fraud and theft discussed above may be considered part of a wider problem of “governance” of P2P and RTP systems. While space precludes a detailed discussion of this issue here (it will be the subject of a forthcoming paper in this series), from an economic perspective, it is important for payment-network operators’ incentives to be aligned with those of users. Among other things, this means that the operator of a payment network should not also have monopoly powers to regulate all other payment networks and PSPs, since this creates a potential conflict of interest whereby the payment network that the regulator operates is privileged relative to other networks and PSPs, thereby undermining competition and harming users.

In practice, central banks often operate at least part of the payment-network infrastructure and have broad regulatory powers with respect to payment-network operations. In such circumstances, conflicts of interest cannot be entirely avoided, but can at least be mitigated by ensuring that there is separation between the division responsible for operating payments infrastructure and the division charged with regulation. As the BIS Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems has noted:

A central bank needs to be clear when it is acting as regulator and when as owner and/or operator. This can be facilitated by separating the functions into different organisational units, managed by different personnel.[52]

Such best practices are followed by central banks such as the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia.[53] By contrast, at the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB), the same unit that operates Pix also regulates other private PSPs.[54]

One of the key advantages of credit cards is that cardholders can pay for goods and services when they face temporary liquidity constraints—i.e., when they have insufficient funds immediately available to make a purchase. Most credit-cards issuers provide cardholders with interest-free credit from the time of a purchase until the bill is due, which typically ranges from 15 to 45 days, depending on when the purchase was made during the billing cycle. If the bill is settled in full by the due date, then no interest is payable. If the bill is not settled in full by the due date, then interest is payable on the outstanding amount.

Unlike payments made using credit cards, those made using a P2P-RTP do not inherently offer the payor the ability to spend more than they have in their account at the time of a purchase. Some P2P payments platforms have, however, developed credit facilities via buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) providers such as Afterpay (owned by Square), Affirm, Flexpay, Klarna, Sezzle, Splitit, and Zip.[55] BNPLs offer various ways to defer payment. For example, payors may be offered an option to defer the payment for a short period (such as four to eight weeks) at 0% interest, in which case the BNPL typically charges the retailer a transaction fee of between 2% and 8% (depending on the consumer’s credit score and the type of merchant).[56] Square charges the purchaser a standard rate of 6% plus a transaction fee of $0.30.[57] Alternatively, payors may be offered longer-term payment solutions, in which case, the merchant pays a transaction fee and the consumer pays the interest.[58]

Nonetheless, unlike credit cards, which automatically provide credit, BNPLs require the user to make an additional step when making a purchase, slowing the process down. And as noted, BNPLs can end up being more costly to the merchant and/or consumer than using a credit card.

P2Ps and RTPs clearly have both advantages and drawbacks compared to other payment systems. They are well-suited for payments where immediacy and finality are required, where the goods or services have already been delivered or are being supplied by a trusted provider, and where the payor is satisfied that the warranties provided by the payee are adequate and easily enforced. For such transactions, payments made using P2Ps and RTPs are in many ways superior to cash, checks, or older EFT-based online debit transactions.

By offering a means of sending credit in real time between banks operating on the same system, RTP rails have facilitated more widespread use of P2P payments. Indeed, it is likely this characteristic, as much as improved bandwidth and processing speeds for online transactions, that explains the dramatic increase in the number of RTP systems over the course of the past decade.

By contrast, P2Ps and RTPs are poorly suited to transactions where immediacy and/or finality are not required, either because the goods or services have not yet been delivered or because of concerns regarding the quality of those goods or services. This is because the finality of P2P and RTPs makes it more difficult for the systems to detect, prevent, and rectify fraud, theft, and mistake. P2Ps and RTPs are thus poorly suited to transactions where goods and services are delivered after payment has been sent and the payor does not have an established trust relationship with the merchant. That includes many online purchases.

In such circumstances, closed-loop or dual-message open-loop payment cards will typically be superior to P2Ps and RTPs. For example, cardholders may dispute charges and make chargebacks if products have not been received or are defective. Acquirers and/or issuers also may delay payment until fraud checks have been completed, reducing the likelihood of a fraudulent transaction and thereby protecting merchants from chargebacks and protecting cardholders from fraud.

P2Ps and RTPs are also less well-suited to paying for goods or services when the payor does not have adequate funds in their bank account. While BNPLs may offer a solution in such cases, in most cases, it will be quicker and in many cases, it will be less costly to use a credit card. Subsequent papers in this series will look in more detail at issues relating to adoption of P2Ps and RTPs, the problem of APP fraud, and governance of RTPs.

[1] P2P is sometimes used in a more restrictive sense to mean “person-to-person”; the broader meaning used here includes person-to-person, person-to-business, and business-to-business.

[2] Marcela Ayres, Brazil’s Central Bank Chief Predicts End of Credit Cards, Reuters (Aug. 12, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/brazils-central-bank-chief-says-credit-card-will-cease-exist-soon-2022-08-12.

[3] For example, the European Central Bank defines clearing as “the process of transmitting, reconciling and, in some cases, confirming transfer orders prior to settlement, potentially including the netting of orders and the establishment of final positions for settlement.” See, All Glossary Entries, European Central Bank, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/services/glossary/html/glossa.en.html (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[4] History of Bacs, Bacs Payment Schemes Ltd. (Feb. 23, 2015), available at https://www.bacs.co.uk/DocumentLibrary/History_of_Bacs.pdf.

[5] History of Nacha and the ACH Network, Nacha (Apr. 20, 2019), https://www.nacha.org/content/history-nacha-and-ach-network.

[6] Id.

[7] As recently as 2012, standard settlement over BACS was 3 days. See, Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems in the United Kingdom (CPSS Red Book), Bank for International Settlement Committee on Payment and Market Infrastructure (2012), at 455, available at https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d105_uk.pdf.

[8] Press Release, Federal Reserve Announces Posting Rules for New Same-Day Automated Clearing House Service, Federal Reserve (Jun. 21, 2010), https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/other20100621a.htm.

[9] Same Day ACH, NACHA, https://www.nacha.org/content/same-day-ach (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[10] CHIPS, Modern Treasury, https://www.moderntreasury.com/learn/chips (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[11] Fedwire Funds Services, Federal Reserve (May 7, 2021), https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/fedfunds_about.htm.

[12] Gara Alfonso et al., Interbank Payment Timing is Still Closely Coupled, Working Paper (Jun. 2022), available at https://www.dnb.nl/media/raafily1/presentation-session-vii.pdf.

[13] The Bank for International Settlements offers the following definition: “Fast payments can be defined by two key features: speed and continuous service availability. Based on these features, fast payments can be defined as payments in which the transmission of the payment message and the availability of final funds to the payee occur in real time or near-real time and on as near to a 24-hour and 7-day (24/7) basis as possible.” See, Fast Payments – Enhancing the Speed and Availability of Retail Payments, Bank for International Settlements (Nov. 2016), at 1, available at https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d154.pdf; Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve notes that: “To be classified as a faster payment, the payment option must 1) enable both payer and payee to see the transaction reflected in their respective account balances immediately and 2) provide funds that the payee can use right after the payer initiates the payment. And because of this, the payment is, by its nature, also irrevocable, meaning it cannot be reversed by the payer or the payer’s financial institution (FI) after it is sent.” See, Fast, Faster, Instant Payments: What’s in a Name?, Federal Reserve, https://www.frbservices.org/financial-services/fednow/instant-payments-education/whats-in-a-name.html (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[14] Alfonso, supra note 12, at 5.

[15] The Distinctions Between Faster Payments and Real-Time Payments, Payments Journal (Aug. 18, 2020), https://www.paymentsjournal.com/the-distinctions-between-faster-payments-and-real-time-payments.

[16] The name is an abbreviation of “Mobile Pesa”; Pesa means money in Swahili.

[17] Mobile Money: From Transferring Cash by SMS to a Digital Payments Ecosystem (2000–20) in Russell Southwood, Africa 2.0, Manchester University Press (2022).

[18] Nick Hughes & Susie Lonie, M-PESA: Mobile Money for the “Unbanked”, Innovations (Winter and Spring 2007), 63-81, available at https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/innovationsarticleonmpesa_0_d_14.pdf.

[19] What is M-PESA?, Vodaphone, https://www.vodafone.com/about-vodafone/what-we-do/consumer-products-and-services/m-pesa (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[20] M-Pesa for Business, https://m-pesaforbusiness.co.ke (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[21] M-Pesa: Credit and Savings, Safaricom, https://www.safaricom.co.ke/personal/m-pesa/credit-and-savings (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[22] M-Pesa, Safaricom, https://www.safaricom.co.ke/personal/m-pesa (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[23] Unified Payments Interface (UPI) Overview, NPCI, https://www.npci.org.in/what-we-do/upi/product-overview (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[24] Statistics of NPCI, NPCI, https://www.npci.org.in/statistics (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[25] Frequently Asked Questions, The Clearing House, https://www.theclearinghouse.org/payment-systems/rtp/institution (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[26] RTP Quarterly Payment Activity (1Q23), The Clearing House, https://www.theclearinghouse.org/payment-systems/rtp.

[27] Julian Morris, Is Pix Really the End of Credit Cards? Truth on the Market (Sep. 28, 2022), https://truthonthemarket.com/2022/09/28/is-pix-really-the-end-of-credit-cards.

[28] About the FedNow Service, Federal Reserve Board, https://www.frbservices.org/financial-services/fednow/about.html (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[29] The Real-Time Rail: Canada’s Fastest Payment System, Payments Canada, https://payments.ca/systems-services/payment-systems/real-time-rail-payment-system (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[30] Prime Time for Real-Time Global Payments Report, ACI Worldwide (2023), https://www.aciworldwide.com/real-time-payments-report.

[31] RTP Quarterly Payment Activity (1Q23), The Clearing House, https://www.theclearinghouse.org/payment-systems/rtp (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[32] Federal Reserve Payments Study (FRPS), Federal Reserve Board (2023), https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/fr-payments-study.htm.

[33] Tyler DeLarm, Credit Card Authorization Hold- How and When to Use, Chargeback Gurus (Dec. 26, 2021), https://www.chargebackgurus.com/blog/credit-card-authorization-holds.

[34] Stan Sienkiewicz, The Evolution of EFT Networks from ATMs to New On-Line Debit Payment Products, Fed. Rsrv. Bank of Phila (Apr. 2002), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=927473.

[35] Enable Individuals and Businesses to Move Money Globally, Visa, https://usa.visa.com/run-your-business/visa-direct/use-cases.html (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023); Send Money Quickly, Securely and Simply, Mastercard, https://www.mastercard.us/en-us/business/large-enterprise/grow-your-business/mastercard-send/mc-send-domestic-payments.html (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[36] Federal Reserve Board, supra note 32.

[37] It should be noted that on the other side of the equation is “disbursement float,”—i.e., funds that have not yet left the payor’s account and are thus still available to the payor. The float is thus effectively a short-term loan made by the payee to the payor.

[38] For example, these features will be enabled for FedNow payments. See, The Real Value of Real-Time Payments, J.P. Morgan, https://www.jpmorgan.com/solutions/treasury-payments/insights/real-value-real-time-payments (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[39] Skimming Fraud, Corporate Finance Institute (Jun. 8, 2020), https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/esg/skimming-fraud.

[40] Cash Larceny, Corporate Finance Institute (Jun. 7, 2020), https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/risk-management/cash-larceny.

[41] Check Fraud: A Guide to Avoiding Losses, U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (Feb. 1999), available at https://www.occ.gov/publications-and-resources/publications/banker-education/files/pub-check-fraud.pdf.

[42] David L Stearns, “Think of it as Money”: A History of the VISA Payment System, 1970–1984, PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh (Aug. 2007), at 46 and 57-59, available at https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/2672/Stearns%20DL%20thesis%2007.pdf.

[43] Julian Morris & Todd J. Zywicki, Regulating Routing in Payment Networks, International Center for Law & Economics (Aug. 17, 2022), available at https://laweconcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Regulating-Routing-in-Payment-Networks-final.pdf.

[44] Card Fraud Losses Dip to $28.58 Billion, Nilson Report (Dec. 2021), 5-7, available at https://nilsonreport.com/upload/content_promo/NilsonReport_Issue1209.pdf.

[45] Id.; see also, Card-Not-Present (CNP) Fraud Mitigation Techniques, U.S. Payments Forum (2020), available at https://www.uspaymentsforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/CNP-Fraud-Mitigation-Techniques-WP-FINAL-July-2020.pdf.

[46] Over £1.2 Billion Stolen Through Fraud In 2022, With Nearly 80 Per Cent of APP Fraud Cases Starting Online, UK Finance (May 11, 2023), https://www.ukfinance.org.uk/news-and-insight/press-release/over-ps12-billion-stolen-through-fraud-in-2022-nearly-80-cent-app.

[47] Bryan Harris, Brazil’s Criminals Turn to Flash Kidnapping as They Take Advantage of New Tech, Financial Times (Sep. 3, 2021), https://www.ft.com/content/225fd97c-ef82-4dfa-b09b-97b1671e1e00.

[48] Id.

[49] Alana Fernandes, Brasileiros Estão Apostando no Celular do PIX, Edital Concursos Brasil (May 21, 2022), https://editalconcursosbrasil.com.br/noticias/2022/05/brasileiros-estao-apostando-no-celular-do-pix-entenda-o-que-e-e-como-usar.

[50] The first, in late September 2021, resulted in the theft of information from nearly 400,000 Pix users due to a systems failure at state-owned Bank of the State of Sergipe (Banese). See Angelica Mari, Brazilian Data Protection Authority Investigates First PIX Data Leak, ZDNet (Oct. 6, 2021), https://www.zdnet.com/article/brazilian-data-protection-authority-investigates-first-pix-data-leak. See also Larissa Garcia & Alvaro Campos, New Leak Threatens Pix’s Credibility Central Bank Reports a Third Hacker Attack in Six Months, Now With 2,112 Keys Exposed, Valor International (Feb. 3, 2022). The second breach occurred in late January 2022 and involved the theft of data relating to approximately 160,000 Pix users from Acesso Pagamentos. See Gabriel Shinohara, Banco Central Comunica Vazamento de Dados de 160,1 Mil Chaves Pix da Acesso Pagamentos Segundo o BC, Não Houve Vazamento de Dados Sensíveis Como Senhas e Saldos, O Globo (Jan. 21, 2022), https://oglobo.globo.com/economia/banco-central-comunica-vazamento-de-dados-de-1601-mil-chaves-pix-da-acesso-pagamentos-25362574. The third breach, reported in February 2022 but relating to an incident in early December 2021, involved the theft of data from around 2,100 Pix users from LogBank. See Fernanda Capelli, Central Bank Confirms Another Leak of Pix Keys from Logbank, Programadores Brasil (Feb. 4, 2022), https://programadoresbrasil.com.br/en/2022/02/see-central-bank-confirms-yet-another-logbank-pix-key-leak.

[51] New Banking Trojan Targeting 100M Pix Payment Platform Accounts, Dark Reading (Feb 7, 2023), https://www.darkreading.com/risk/new-bank-trojan-targeting-100m-pix-payment-platform-accounts; PixPirate: A New Brazilian Banking Trojan, Cleafy (Feb. 3, 2023), https://www.cleafy.com/cleafy-labs/pixpirate-a-new-brazilian-banking-trojan.

[52] Central Bank Oversight of Payment and Settlement Systems, Bank for International Settlements Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (May 2005), available at https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d68.pdf.

[53] Policies: The Federal Reserve in the Payments System, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Jan. 2001), https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/pfs_frpaysys.htm; Managing Potential Conflicts of Interest Arising from the Bank’s Commercial Activities, Reserve Bank of Australia (Feb. 2022), https://www.rba.gov.au/payments-andinfrastructure/payments-system-regulation/conflict-of-interest.html.

[54] Julian Morris, Central Banks and Real-Time Payments: Lessons from Brazil’s Pix, IInternational Center for Law & Economics (Jun. 1, 2022), at 13, available at https://laweconcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Lessons-from-Brazils-Pix.pdf.

[55] Erin Gregory, How Does Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) Work for Businesses?, Tech Radar (Mar. 4, 2022), https://www.techradar.com/features/how-does-buy-now-pay-later-bnpl-work-for-businesses; Jaros?aw ?ci?lak, Top 10 Buy Now Pay Later Companies to Watch in 2022, Code & Pepper (Aug. 5, 2022), https://codeandpepper.com/buy-now-pay-later-2022.

[56] Id.

[57] Bring in More Business With Buy Now, Pay Later, Square, https://squareup.com/us/en/buy-now-pay-later (last accessed Aug. 19, 2023).

[58] Id.

I. Introduction As part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), signed by President Joe Biden in November 2021, Congress provided $42.5 billion for . . .

As part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), signed by President Joe Biden in November 2021, Congress provided $42.5 billion for broadband deployment, mapping, and adoption projects through the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program, with the stated goal of directing the funds to close the so-called “digital divide.”[1] But actions by pole owners—such as refusing to allow broadband companies to attach their lines on reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms—threaten to slow broadband deployment significantly.

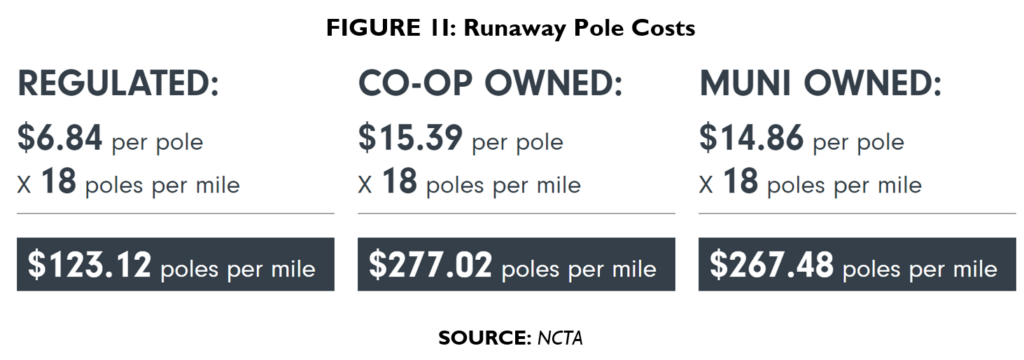

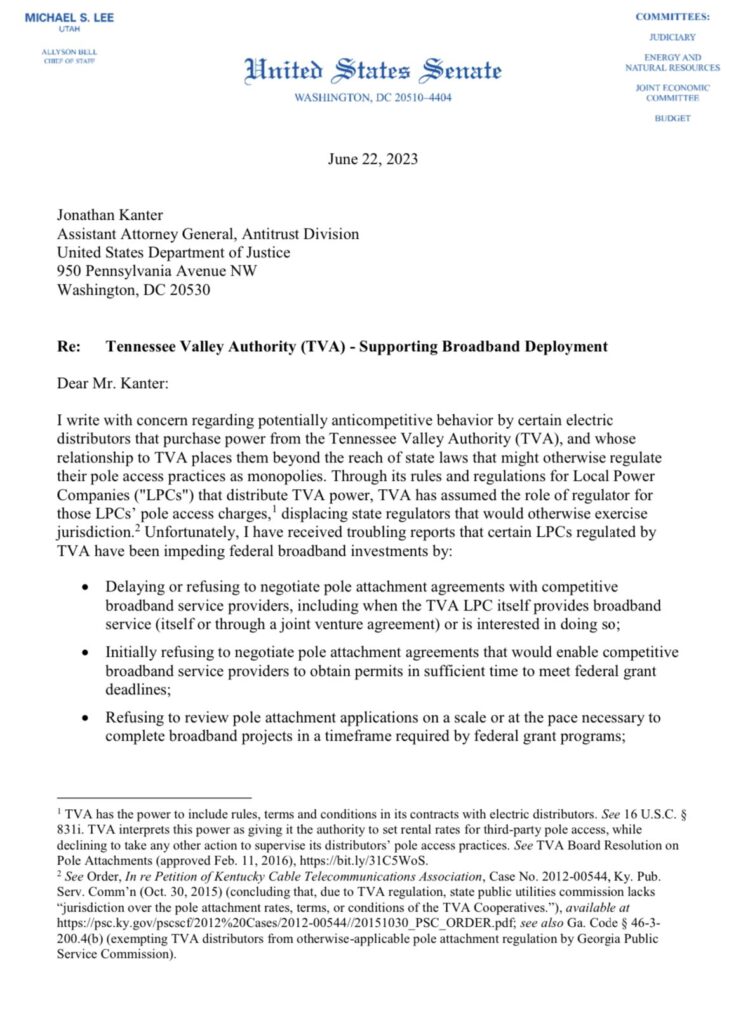

In a recent letter to Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter, Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) put forth the argument that the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) should take action to address abuses of the pole-attachment process by local power companies (LPCs) regulated by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).[2] His concern is that such abuses threaten to slow broadband deployment, especially to rural areas served by the TVA and the LPCs.[3] Among the abuses he details are:

Section 224 of the Communications Act exempts municipal and electric-cooperative (“coop”) pole owners, such as the LPCs, from oversight by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[5] At the same time, the TVA’s authority over pole attachments is not subject to oversight by state governments.[6] This loophole means that it is the TVA, not the FCC, that sets the rates for pole attachments. The TVA’s rates are significantly higher than those of the FCC, [7] and the TVA’s LPCs often are able to avoid the access requirements that states and the FCC typically require.[8]

But avoiding state and FCC regulatory oversight is not the only loophole that the TVA and its LPCs can exploit: the TVA and the government-owned LPCs also may not be subject to antitrust law. These entities hold a resource critical for broadband deployment, while it is essentially impossible for private providers to build competing pole infrastructure. In situations like this, government entities that participate as firms in the marketplace—known in the literature as “state-owned enterprises” (SOEs)—should be subject to antitrust law in order to ensure access by private competitors.

Sen. Lee is correct that the DOJ should examine the practices of the TVA and its LPCs under antitrust law. Antitrust clearly applies to those LPCs that are private coops, which have no immunities. But Congress should clarify that the TVA and government-owned LPCs are likewise subject to antitrust law when they act according to their “commercial functions” or as “market participants.” They should also consider bringing the TVA and all of its LPCs under the purview of the FCC’s Section 224 authority over pole attachments.

SOEs’ incentives differ from those of privately owned businesses. Most notably, while a private business must pass the profit-and-loss test, SOEs often are not subject to the same constraints. This difference may manifest through setting up legal SOE monopolies against which no other firm can compete; exempting SOEs from otherwise generally applicable laws; extending explicit subsidies to SOEs, whether in the form of taxpayer-financed appropriations or government-backed bonds (which the government explicitly or implicitly promises to repay, if necessary); or cross-subsidies from other government-owned monopoly businesses.

As a result, SOEs do not need to maximize profits (with Armen Alchian’s caveat that private market participants may be modeled as profit maximizers even if that isn’t their true motivation[9]) and can pursue other goals. In fact, this is exactly why some supporters of SOEs like them so much: they can pursue the so-called “public interest” by providing ostensibly high-quality products and services at what are often below-market prices.[10]

But this freedom comes at a cost: not only can SOEs inefficiently allocate societal resources away from their highest-valued uses, but they may actually have greater incentive to abuse their positions in the marketplace than private entities. As David E.M. Sappington and J. Gregory Sidak put it:

[W]hen an SOE values an expanded scale of operation in addition to profit, it will be less concerned than its private, profit-maximizing counterpart with the extra costs associated with increased output. Consequently, even though an SOE may value the profit that its anticompetitive activities can generate less highly than does a private profit-maximizing firm, the SOE may still find it optimal to pursue aggressively anticompetitive activities that expand its own output and revenue. To illustrate, the SOE might set the price it charges for a product below its marginal cost of production, particularly if the product is one for which demand increases substantially as price declines. If prohibitions on below-cost pricing are in effect, an SOE may have a strong incentive to understate its marginal cost of production or to over-invest in fixed operating costs so as to reduce variable operating costs. A public enterprise may also often have stronger incentives than a private, profit-maximizing firm to raise its rivals’ cost and to undertake activities designed to exclude competitors from the market because these activities can expand the scale and scope of the SOE’s operations.[11]

Here, entities like the TVA and many of the government-owned LPCs that sell the electricity it produces are simply not subject to the same profit-and-loss test that a private power company would be. But even more importantly for the discussion of broadband buildout, many of these government-owned LPCs also provide broadband services (or intend to), effectively using their position as a monopoly provider of electricity to cross-subsidize their entry into the broadband marketplace. Moreover, LPCs often own the electric poles and control decisions about whether and at what rates to rent them to third parties (subject to TVA rate regulations), including to private broadband providers that may compete with the LPCs’ municipal-broadband offerings.

This raises two significant issues for competition policy:

In Verizon Communication Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko LLP,[13] the U.S. Supreme Court explained the reasoning behind a very limited duty to deal under antitrust law:

Compelling… firms to share the source of their advantage is in some tension with the underlying purpose of antitrust law, since it may lessen the incentive for the monopolist, the rival, or both to invest in those economically beneficial facilities.[14]

In sum, a private market participant is constantly looking to acquire monopoly power by innovating and better serving customers, and temporary monopolies—acquired through a legitimate competitive process—are not unlawful. If successful, this process provides incentive for more innovation and competition, including incentives for competitors to build their own infrastructure.