Competition in the Market for Groceries

Background: In October 2022, supermarkets Kroger and Albertsons announced their intent to merge in a $24.6 billion deal. The combined company would be the third-largest food and grocery retailer, behind Walmart and Amazon, and would account for roughly 9% of nationwide sales. Based on the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) recently released draft merger guidelines and comments by FTC Chair Lina Khan, it appears likely that the agency will move to block the merger, even if the companies offer to divest stores to competing chains.

But… If the FTC does seek to block the deal, it will face an uphill battle. The retail industry has changed dramatically over the past few decades. Partly due to the tremendous growth of supercenters, club stores, and online retail, U.S. consumers are no longer “one-stop shoppers.” These market changes have placed tremendous competitive pressure on traditional retail.

Some of the deal’s critics have also raised concerns about the prospect of monopsony power in labor markets, but these claims are speculative at best and unlikely to hold up in court.

AMERICANS AREN’T ONE-STOP SHOPPERS

The FTC has for decades clung to a narrow definition of supermarkets that includes only those stores that allow consumers to buy nearly all of their weekly food and grocery needs in a single trip. This definition encompasses traditional food and grocery retailers, such as Kroger and Albertsons, as well as supercenters with grocery sections, such as some Walmart and Target stores. But critically, the FTC’s definition excludes warehouse clubs like Costco and e-commerce services like Amazon.

The FTC’s hypothetical customer is no longer typical. Grocery shopping has shifted toward more frequent shopping trips across various formats, including not only warehouse clubs and e-commerce services, but online-delivery platforms like Instacart; limited-assortment stores like Trader Joe’s and Aldi; natural and organic markets like Whole Foods; and ethnic-specialty stores like H Mart.

Due to these enormous changes, the market definition used in earlier FTC consent orders likely will be, and should be, challenged. This means there are fewer geographic areas where the deal would lead to problematic post-merger market positions.

COMPETITION FROM SUPERCENTERS, CLUB STORES, & ONLINE RETAIL

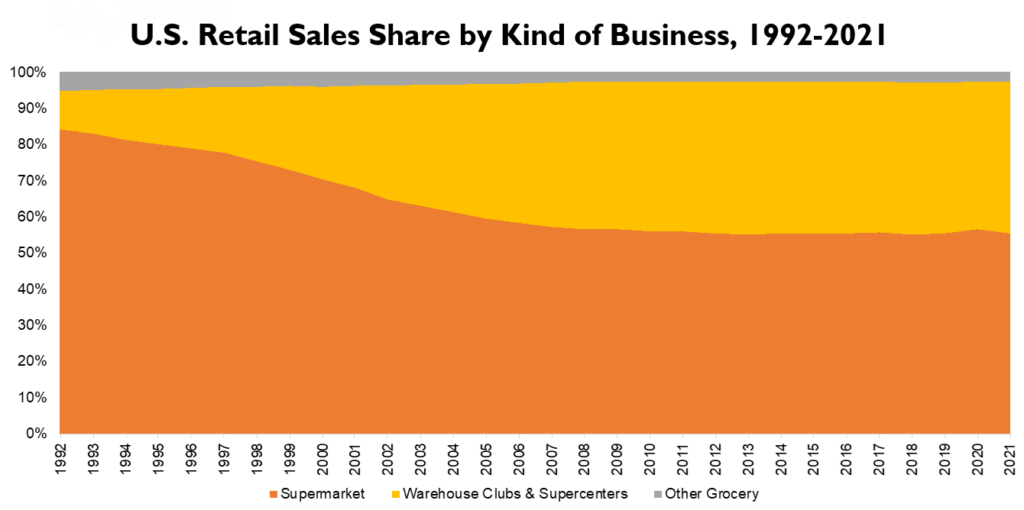

Over the past 25 years or so, warehouse clubs and supercenters like Walmart have doubled their share of retail sales, while supermarkets’ share has dropped by more than 25%. Indeed, according to data from the industry magazine Progressive Grocer, if the merger goes through, Kroger/Albertsons will still be about 50% smaller than Walmart.

Along similar lines, online shopping and home delivery have grown from niche services that served only 10,000 households nationwide a quarter century ago to a scenario in which 12.5% of U.S. consumers now purchase groceries mostly or exclusively online.

Amazon is now the second-largest food and grocery retailer in the United States. Meanwhile, millions of consumers use delivery services like Instacart to purchase food and groceries from supermarkets, supercenters, club stores, wholesalers, and ethnic markets.

These new businesses place significant competitive pressure on traditional retailers, making the prospect of post-merger market power even more unlikely.

MISPLACED LABOR-MARKET CONCERNS

Some opponents of the merger argue that it would lead to monopsony power in labor markets and depress supermarket employee wages. But these concerns are overblown and will be nearly impossible to demonstrate if the merger were to be litigated.

The market for labor in the retail sector is highly competitive, with workers having a wide range of alternative employment options. More importantly, both Kroger and Albertsons are highly unionized firms. Through their collective-bargaining agreements, these unions exert their own market power.

THE HAGGEN FIASCO: LESSONS LEARNED

Finally, some point to Haggen’s disastrous acquisition of stores spun-off from the Albertsons/Safeway merger as evidence that divestitures don’t work. But several factors idiosyncratic to Haggen and its acquisition strategy led to that failure, rather than the divestiture itself.

Before it acquired the stores, Haggen was a small regional chain with only 18 stores, mostly in Washington State. In addition, buying the stores left Haggen’s owners heavily in debt.

These issues could—and should—have been addressed when the FTC and the merging parties were negotiating their consent order. Today’s enforcers should thus learn from the Haggen experience—by devising workable remedies—rather than view it as a justification to reject reasonable divestiture options.

For more on this issue, see the International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE) issue brief “Five Problems with a Potential FTC Challenge to the Kroger/Albertsons Merger.”