Gerrymandered Market Definitions in FTC v Amazon

Introduction Market definition is a critical component of any antitrust case. Not only does it narrow consideration to a limited range of relevant products or . . .

Introduction

Market definition is a critical component of any antitrust case. Not only does it narrow consideration to a limited range of relevant products or services but, perhaps more importantly, it specifies a domain of competition at issue in an antitrust case—that is, the nature of the competition between certain firms that might (or might not) be harmed by the conduct of the defendant. As Greg Werden has characterized it:

Alleging the relevant market in an antitrust case does not merely identify the portion of the economy most directly affected by the challenged conduct; it identifies the competitive process alleged to be harmed.[1]

Unsurprisingly, plaintiffs—not least, antitrust agencies—are often tempted to define artificially narrow markets in order to reinforce their cases (sometimes, downright ridiculously so[2]). The consequence is not merely to artificially inflate the market significance of the firm under scrutiny, although it does do that; it is also to misapprehend and misdescribe the true nature of competition relevant to the challenged conduct.

This unfortunate trend—allegations of harm to artificially constrained and gerrymandered markets—is exemplified in the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) recent proceedings against Amazon.

The FTC’s complaint against Amazon describes two relevant markets in which anticompetitive harm has allegedly occurred: (1) the “online superstore market” and (2) the “online marketplace services market.”[3]

Unfortunately, both markets are excessively narrow, thereby grossly inflating Amazon’s apparent market share and minimizing the true extent of competition. Moreover, the FTC’s approach to market definition here—lumping together wildly different products and wildly different sellers into single “cluster markets”—grossly misapprehends the nature of competition relating to the challenged conduct.

First, the FTC’s complaint limits the online-superstore market to online stores only, and further limits it to stores that have an “extensive breadth and depth”[4] of products. The latter means online stores that carry virtually all categories of products (“such as sporting goods, kitchen goods, apparel, and consumer electronics”[5]) and that also have an extensive variety of brands within each category (such as Nike, Under Armor, Adidas, etc.).[6] In practice, this definition excludes leading brands’ private channels (such as Nike’s online store),[7] as well as online stores that focus on a particular category of goods (such as Wayfair’s focus on furniture).[8] It also excludes the brick-and-mortar stores that still account for the vast majority of retail transactions.[9] Firms with significant online and brick-and-mortar sales might count, but only their online sales would be considered part of the market.

Second, the online-marketplace-services market is limited to online platforms that provide access to a “significant base of shoppers”;[10] a search function to identify products; a means for the seller to set prices and present product information; and a method to display customer reviews. This implies that current Amazon sellers can’t reach consumers through mechanisms that don’t incorporate all these specific functions, even though consumers regularly use multiple services and third-party sites that accomplish the same thing (e.g., Google Shopping, Shopify, Instagram, etc.)[11] Moreover, it implies that these myriad alternative channels do not constrain Amazon’s pricing of its services.

Documents identified in the complaint do appear to demonstrate that Amazon pays substantial attention to competition from online superstores and online marketplaces. But cherry-picked business documents do not define economically relevant markets.[12] At trial, Amazon will doubtless produce a host of ordinary-course documents that show significant competition from a wide array of competitors on both sides of its retail platform. The scope of competition that the FTC sketches—based on a few documents from among tens of thousands—is a public-relations and litigation tactic, but not remotely the full story.

Third, the FTC’s casual use of “cluster markets,” which lump together distinct types of products and different types of sellers into single markets, may severely undermine the commission’s case. It’s one thing to group, say, all recorded music into a single market (despite the lack of substitutability between, say, death metal and choral Christmas music), but it’s another thing entirely to group batteries and bedroom furniture into a single “market,” just because Amazon happens to facilitate sales of both.

Fourth and finally, it is notable that the relevant markets alleged in the FTC’s complaint draw a distinct line between the seller and buyer sides of Amazon’s platform. Implicit in this characterization is the rejection of cross-market effects as a justification for Amazon’s business conduct. Some of the FTC’s specific concerns—e.g., the alleged obligation imposed on sellers to use Amazon’s fulfillment services to market their products under Amazon’s Prime label—have virtually opposite implications for the seller and buyer sides of the market. Arbitrarily cordoning off such conduct to one market or the other based on where it purportedly causes harm (and thus ignoring where it creates benefit) mangles the two-sided, platform nature of Amazon’s business and would almost certainly lead to its erroneous over-condemnation.[13]

Ultimately, what will determine the scope of the relevant markets will be economic analysis based on empirical data. But based on the FTC’s complaint, public data, and common sense (the best we have to go on, for now), it seems implausible that the FTC’s conception of distinct, and distinctly narrow, relevant markets will comport with reality.

An artificially narrow and gerrymandered market definition is a double-edged sword. If the court accepts it, it’s much easier to show market power. But the odder the construction, the more likely it is to strain the court’s credulity. The FTC has the burden of proving its market definition, as well as competitive harm. By defining these markets so narrowly, the FTC has ensured it will face an uphill battle before the courts.

I. The Alleged ‘Online Superstore’ Market

A first weakness of the FTC’s suit pertains to the alleged “online superstore market.” This market definition excludes the following: (1) brick-and-mortar retailers, (2) brick-and-mortar sales by firms that do considerable business online and in-person, and (3) online retailers that don’t meet the definition of a “superstore.”[14] The FTC’s market definition also excludes sales of perishable grocery items.[15] The agency argues that consumers don’t consider these other types of retailers to be substitutes for online superstores.[16] This seems dubious, and the FTC’s complaint does little to dispel the doubt.

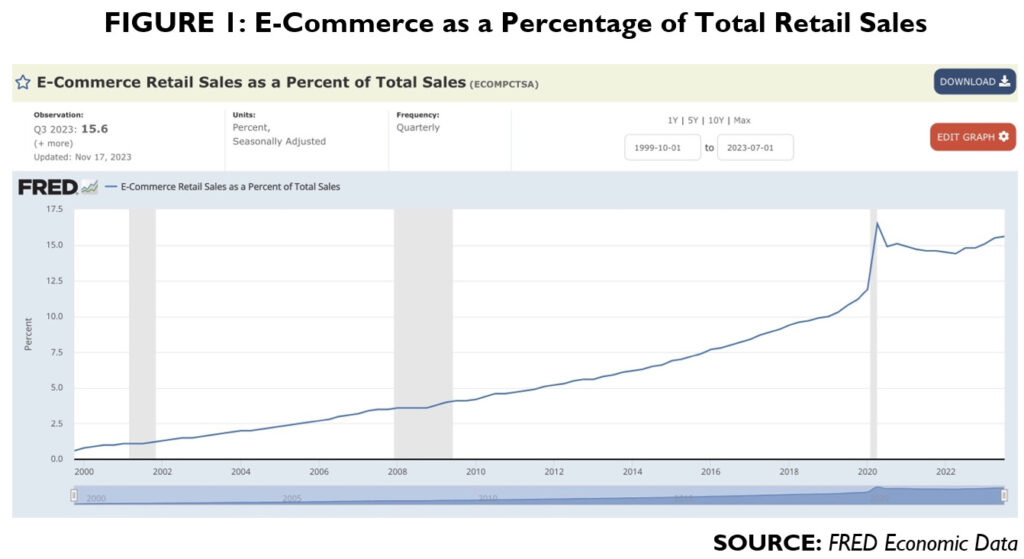

To see how the market definition tilts the balance, consider the FTC’s allegation that Amazon dominates the online-superstore market with approximately 82% market share.[17] That is, Amazon is reported to have approximately 82% market share (in gross merchandise value, or “GMV”), provided we exclude perishables, and consider the market to comprise solely U.S. online sales by Amazon, Walmart, Target, and eBay, but no other vendors. Note, for example, that Walmart, Target, and Costco all have both online and in-person sales at brick-and-mortar stores, but Costco’s online sales are excluded from the online-superstore category, presumably due to their relatively limited scale and scope. But counting both online and in-person sales, it turns out that twelve-month trailing revenue at Costco is reported to be more than double that of Target, which is included in the FTC’s online-superstore category.[18] Amazon’s share of overall online retail is substantial, but it’s much smaller (37.6%) than its share of a purported market that comprises Amazon, Walmart online, Target online, eBay, and nobody else.[19] Indeed, if one includes total retail sales, then Walmart leads Amazon, not vice versa.[20] And while e-commerce may be substantial and growing, it still represents only about 15% of U.S. retail.[21]

There are countless examples where consumers cross-shop online and offline—televisions and other electronics, clothing, and sporting goods (among many others) spring to mind. Indeed, most consumers would surely be hard-pressed to identify any product they’ve purchased from Amazon that they have not, at some point, also purchased from an offline or non-superstore retailer.

Defining a market with reference to a single retailer’s particular product offering—that is, by a single channel of distribution—is unlikely to “identif[y] the competitive process alleged to be harmed.”[22] In fact, for consumers, it doesn’t identify a product at all, and ends up excluding a host of competing sellers that offer economic substitutes for the products consumers actually buy.[23] By failing to do so, the FTC’s purported market definition is woefully deficient in describing the scope of competition: “Including economic substitutes ensures that the relevant product market encompasses ‘the group or groups of sellers or producers who have actual or potential ability to deprive each other of significant levels of business.’”[24]

A. Brick-and-Mortar Competes with Amazon Because Shopping Is Not the Same Thing as Consuming

While it may be that some consumers do not consider offline vendors or non-superstores to be substitutes, it does not follow that such rivals don’t impose competitive constraints on online superstores.

If a hypothetical monopolist raises prices, some consumers—perhaps many, perhaps even most—may switch to a brick-and-mortar retailer. That may be enough to constrain the monopolist’s pricing. How many might switch, and the extent to which that constrains pricing, are empirical questions, but there is no question that some consumers might switch: retail multi-homing is common.

And the constraints on switching are far weaker than the FTC claims. The complaint observes that 1) brick-and-mortar retailers are less convenient because it takes time to go to a physical store, 2) stores are not open for shopping at all hours, and 3) consumers may have to visit multiple stores to buy the necessary items.[25]

Online shopping is almost certainly quicker than offline—at least, once one is sitting in front of a computer with Internet access. But the complaint seems to conflate shopping with consuming.

Even with Amazon’s impressive fulfillment and delivery network, if a consumer needs a product that very moment or even that day, a brick-and-mortar retailer may be preferable. The same may be true in circumstances in which a consumer wants to see a product in person, try on clothing, consult an experienced salesperson, etc. And while some consumers may enjoy shopping, they may or may not prefer the experience of online shopping.

More generally and more to the point, consumers purchase goods to use and consume them. Online stores may be “always open,” but shipping and delivery are not instantaneous. That one can shop online at all hours may be convenient, but it may do nothing to hasten the ability to consume the items purchased.

Meanwhile, brick-and-mortar retailers typically have websites that show their inventory and pricing online. Consumers can, accordingly, comparison shop across e-commerce and brick-and-mortar vendors, even when the brick-and-mortar retailers have closed for the evening.

B. ‘Depth and Breadth’ Isn’t Solely Available from Superstores, and Consumers Buy Products, Not Store Types

Consumers within the “online superstore market” may be able to prevent a hypothetical monopolist from raising prices by switching to other online channels that don’t qualify as a “superstore,” as defined by the FTC.

For example, if a consumer is looking for sporting goods, she can shop at an online superstore, or she can shop at Dick’s online, REI online, or Bass Pro online, all of which have an exceptional “depth and breadth” of items.[26] Alternatively, if the consumer is shopping for a Columbia Sportswear jacket, in addition to the sporting-goods retailers listed, she can also shop on Columbia’s website[27] or at any other online-clothing retailer that carries Columbia jackets (e.g., Macy’s or Nordstrom[28]).

The complaint anticipates and responds to this concern by saying that non-superstore online retailers (as well as brick-and-mortar retailers) lack the depth and breadth of products sold by superstores.[29] But so what? For many consumers, Amazon purchases are made one (or a few) item(s) at a time. When consumers need a bolt cutter, they log in and order it, and when they need a pair of sneakers the next day, they log in and order that. They don’t wait to buy the bolt cutter until they are ready to buy sneakers (i.e., people don’t typically log in to Amazon with a shopping list and purchase multiple items at the same time, except perhaps for perishable groceries, which are excluded from the proposed market). Whether the consumer is buying one item or three or five, a purchase that bundles products across the broad scope of the online-superstore market is not at all the norm.

Indeed, part of the purported advantage of online shopping—when it’s an advantage—is that consumers don’t have to bundle purchases together to minimize the transaction costs of physically visiting a brick-and-mortar retailer. Meanwhile, another part of the advantage of online shopping is the ease of comparison shopping: consumers don’t even have to close an Amazon window on their computers to check alternatives, prices, and availability elsewhere. All of this undermines the claim that one-stop shopping is a defining characteristic of the alleged market.

Data are hard to come by (and the data will ultimately demonstrate whether and to what extent the complaint portrays reality), but public sources indicate that the average number of units per transaction is less than three (admittedly, this is worldwide, and for all online e-commerce, not just Amazon).[30] This does not suggest that shoppers demand extensive “depth and breadth” each time they shop online.

Meanwhile, important lacunae in Amazon’s offerings belie the notion that it offers a true “depth and breadth” that transcends competitive constraints from other retailers. The fact that Nike, on the seller side, doesn’t view Amazon as an essential marketplace[31]—in other words, it believes it has plenty of alternative, competing channels of distribution—has important consequences for the FTC’s market definition on the consumer side. It’s difficult to conceive of a retailer offering anything approaching a comprehensive “depth and breadth” of footwear without offering any Nike shoes. For consumers who buy shoes, Amazon is hardly a unique outlet, and finding even a minimally suitable range of options requires shopping elsewhere, either in combination with Amazon or in its stead.

But the implications are even greater. Because the FTC has grouped sales of all products together—not just footwear or even apparel—and defined the relevant market around that broad clustering of disparate products, can it really be said that Amazon is a “one-stop-shop” at all if it doesn’t offer Nike shoes?

The example may seem trivial, but it aptly illustrates the inherent error in defining the product market essentially by the offerings of a single entity. Necessarily, those offerings will be unique and affected by a host of seller/buyer interactions specific to that company. And in many cases, those specific inclusions and exclusions may be significantly more important than the simple number of SKUs on offer (which is essentially the basis for including Walmart and Target online, but excluding, say, Costco online from the FTC’s “superstores” market).

Further, despite its repeated reliance on “depth and breadth,” the complaint ignores e-commerce aggregators, which allow consumers to search products and pricing across an incredible variety of retailers. Google Shopping is, of course, the most notable example—and, for such a prominent example, curiously absent from the complaint. Through Google Shopping—among other sites—consumers can see extensive results in one place for almost any product, including across all categories and across many brands (the breadth-and-depth factors relied upon by the complaint). Indeed, while many product searches today begin at Amazon, a huge amount of online shopping takes place via Google.[32]

Moreover, online shoppers regularly use third-party sites to research (shop) for products, and these, too, aggregate information from across a huge range of sources. As Search Engine Land reports:

Reviews and ratings can make or break a sale more than any other factor, including product price, free shipping, free returns and exchanges, and more.

Overall, 77% of respondents said they specifically seek out websites with reviews—and this number was even higher for Gen Z (87%) and millennials (81%).[33]

While Amazon is where consumers most often read reviews (94%), other retail websites (91%), search engines (70%), brand websites (68%), and independent review sites (40%) are all significant.[34] And yet, despite their manifest importance in the competitive process of online retail, the FTC’s complaint entirely dismisses the significance of shopping aggregators and non-Amazon, product-review sources.

II. The Alleged ‘Online Marketplace Services’ Market

The complaint is similarly flawed when it assesses the scope of competition from the point of view of sellers.

The complaint endeavors to distinguish and exclude from the market for online marketplace services all other methods by which a seller can market and sell its products to end consumers. For instance, the complaint distinguishes online marketplaces from online retailers where the seller functions as a vendor (i.e., it transfers title to the retailer) and those where sellers provide their own storefronts or sell directly through social media and other aggregators using “software-as-a-service” (“SaaS”) to market products (e.g., Shopify and BigCommerce).[35]

The complaint alleges that neither operating as a vendor nor utilizing SaaS is “reasonably interchangeable”[36] with online marketplace services—the key language from the Brown Shoe case.[37] But merely saying so does not make it true. Service markets can display differentiated competition, just as product markets do. Superficial—and even significant—differences among services do not, in themselves, establish that they are not competitors.

First, where sellers operate as vendors by transferring title to another party to sell the product (either online or at a brick-and-mortar retailer), they could very well constrain the costs that a hypothetical monopolist imposes on sellers. For example, if a hypothetical monopolist increased prices or decreased quality for selling a product, why would Nike not transfer its products away from the monopolist and toward Foot Locker, Macy’s, or any other number of retailers where Nike operates as a vendor? Or why not rely on Nike’s own website, selling directly to the consumer? In fact, Nike has already done this. In 2019, Nike stopped selling products to Amazon because it was dissatisfied with Amazon’s efforts to limit counterfeit products.[38] Instead, Nike opted to sell directly to its consumers or through its other retailers (both online and offline, of course).

The same can be said for sellers without well-known brands or those who opt to use SaaS to sell their products. Certainly, there are differences between SaaS and online-marketplace services, but that doesn’t mean that a seller can’t or won’t use SaaS in the face of increased prices or decreased quality from an online marketplace. Notably, Shopify claims to be the third-largest online retailer in the United States, with 820,000 merchants selling through the platform.[39] It’s remarkable that it is completely absent from the FTC’s market definition.

Also remarkable is that he FTC’s complaint alleges that SaaS providers are not in the relevant market because:

SaaS providers, unlike online marketplace service providers, do not provide access to an established U.S. customer base. Rather, merchants that use SaaS providers to establish direct-to-consumer online stores must invest in marketing and promotion to attract U.S. shoppers to their online stores.[40]

This is remarkable because a significant claim in the FTC’s complaint is that Amazon has “degraded” its service by introducing sponsored search results, “litter[ing] its storefront with pay-to-play advertisements,” and allegedly requiring (some would say enabling…) sellers to pay for marketing and promotion.[41] It’s unclear why the need to invest in marketing and promotion to attract shoppers to one’s online storefront is qualitatively different than the need to invest in marketing and promotion to attract shoppers to one’s products on Amazon’s platform.

Indeed, the notion that large platforms like Amazon simply “provide access” to consumers glosses over the immense work that such access entails. Amazon and similar platforms (including, of course, SaaS providers) make significant investment in designing and operating user interfaces, matching algorithms, marketing channels, and innumerable other functionalities to convert undifferentiated masses of consumers and sellers into a functional retail experience. Amazon’s value for sellers in providing access to customers must be balanced by the reality that, in doing so, large “superstores” like Amazon also necessarily put a large quantity of disparate sellers in the same unified space.

For obvious reasons, sellers don’t necessarily value selling their products in the same location as other sellers. They do, of course, want access to consumers, but the “marketplace” or “superstore” aspects of Amazon simultaneously impedes that access by congesting it with other sellers and products (and consumers seeking other products). A specialized outlet may, in fact, offer the optimal sales environment: all consumers seeking the seller’s category of goods (but somewhat fewer consumers), and fewer sellers impeding discovery and access (though more selling the same category of goods). A furniture seller may have dozens of online outlets (and, of course, many offline outlets, catalog sales, decorator sales, etc.), and there is little or no reason to think that, by virtue of also offering batteries, clothes, and bolt cutters, Amazon offers anything truly unique to a furniture seller that it can’t get by selling through another distribution channel with a different business model.

The complaint relies heavily on this notion that online-marketplace services deliver a large customer base that cannot be matched by selling as a vendor or using SaaS. (It is entirely unclear if the FTC considers single-category online marketplaces like Wayfair to be in the “online marketplace services” market, a topic to which I return below in the “cluster markets” discussion; it is clear the FTC doesn’t consider Wayfair part of the “online superstores market.”).[42] Again, in this context, the complaint ignores e-commerce aggregators and how they affect sellers’ ability to access customers. Through Google Shopping, consumers can see extensive results for almost any product, including across all categories and across many brands. And Google aggregates product listings without charging the seller.[43] Thus, through Google Shopping, a seller can access a large consumer base that may constrain a hypothetical monopolist in the online-marketplace-services market.

And Google Shopping is not alone. Selling through social media has boomed. According to one source, Instagram is an online-shopping juggernaut.[44] Among other things:

- 130 million people engage with shoppable Instagram posts monthly;

- 72% of users say they made a purchase based on something they saw on Instagram;

- 70% of Instagram users open the app in order to shop; and

- 81% of Instagram users research new products and services on the platform.[45]

Sellers on Instagram can use Meta’s “Checkout on Instagram”[46] service to process orders directly on Instagram, as well as logistics services like Shopify or ShipBob to manage their supply chains and fulfill sales,[47] replicating the core functionality of a vertically integrated storefront like Amazon.

The bottom line is that Amazon is not remotely the only (or, in many cases, even the best) place for sellers to find, market, and sell to consumers. Its superficial differences from other distribution channels are just that: superficial.

III. Cluster Markets

One of the most important problems with the FTC’s alleged relevant markets is that they treat all products and all sellers the same. They effectively assume that consumers shop for bolt cutters the same way they shop for furniture, and that Adidas sells shoes the same way that drop-shippers sell toilet paper.

Courts have recognized that such an approach—using “cluster markets” to assess a group of disparate products or services in a single market—can be appropriate for the sake of “administrative[ ]convenience.” As the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals noted in Promedica Health v. FTC, “[t]his theory holds, in essence, that there is no need to perform separate antitrust analyses for separate product markets when competitive conditions are similar for each.”[48]

A second basis for clustering is the “transactional-complements” theory, relabeled by the 6th Circuit as the “‘package-deal’ theory.”[49] This approach clusters products together for relevant market analysis when “‘most customers would be willing to pay monopoly prices for the convenience’ of receiving certain products as a package.”[50]

For example, it may be appropriate to refer to a “market for recorded music” even though consumers of music by Taylor Swift probably exert little or no competitive pressure on the price or demand for recordings of, say, Cannibal Corpse. Thus, in the EU’s 2012 clearance (with conditions) of the Universal Music Group/EMI Music merger, the Commission determined that, although classical music may present somewhat different competitive dynamics, there was no basis for defining separate markets by artist or even by genre.[51]

Hospital mergers provide another classic example.[52] Labor and delivery services are not a substitute for open-heart surgery, but the FTC nonetheless frequently defines a market as “inpatient general acute care services” or something similar because of the similar relationship of each to a hospital’s organization and administration, as well as the fact that payers typical demand such services (and hospitals typically provide such services) in combination (even though patients, of course, do not consume them together).

The Supreme Court put its imprimatur on the notion of a cluster market in Philadelphia National Bank, accepting the lower court’s determination that “commercial banking” constituted a relevant market because of the distinctiveness, cost advantages, or consumer preferences of the constituent products.[53]

A. Assessing Cluster Markets

Widespread use (and the occasional fairly serious analysis) of cluster markets notwithstanding, it is worth noting that the economic logic of such markets is, at best, poorly established.

In the UMG/EMI case, for example, the Commission rested on the following factors in concluding that markets should not be separated out by genre (let alone by artist):

The market investigation showed that, by and large, a segmentation of the recorded music market based on genre is not appropriate. First, the borders between genres are often blurred and artists and songs can fit within several genres at the same time. Second, several customers also underline that placing of a song or an album into a specific genre is entirely subjective. Third, a vast majority of customers indicated that they purchase and sell all genres of music.[54]

These facts may all be true, but they do little to permit the inference drawn. Indeed, the first two factors arguably refer only to administrability, not economic reality, and the third is woefully incomplete (e.g., it says little about a potential monopolist’s ability to raise prices if price increases can be passed on to end-consumers in some genres but not others). While the frailties of the market determination may not ultimately have mattered in that case (after all, the parties got their merger, and the Commission presumably brought the strongest case it could), such casual conclusions may well prove problematic elsewhere and do little to advance the logic of the cluster-markets concept.

Similar defects plague the Supreme Court’s endorsement of the theory in PNB. The Court suggests some reasons why, even in its own telling, “some commercial banking products or services”[55] may be insulated from competition, but that still leaves open the possibility that others aren’t, and that the relevant insulating characteristics could be eroded by simple product repositioning, different pricing strategies, or changes in reputation and brand allegiance.

In fact, the defendants in PNB argued before the district court that:

commercial banking in its entirety is not a product line. Rather, they submit it is a business which has two major subdivisions—the acceptance of deposits in which the bank is the debtor, and the making of loans in which the bank is the creditor. Both of these major divisions are further divided by distinct types of deposits and loans. As to many of these functions, there are different types of customers, different market areas, and, most importantly, different types of competitors and competition. With the possible exception of demand deposits, there is an identical or effective substitute for each one of the services which a commercial bank offers.[56]

The court, however, rejected these arguments with little more than a wave of the hand (a conclusion that was then simply accepted by the Supreme Court):

It seems quite apparent that both plaintiff’s and defendants’ positions have some merit. However, it is not the intention of this Court to subdivide a commercial bank into certain selected services and functions. An approach such as this, carried to the logical extreme, would result in many additional so-called lines of commerce. It is the conglomeration of all the various services and functions that sets the commercial bank off from other financial institutions. Each item is an integral part of the whole, almost every one of which is dependent upon and would not exist but for the other. The Court can perceive no useful purpose here in going any further than designating commercial banking a separate and distinct line of commerce within the meaning of the statute. It is undoubtedly true that some services of a commercial bank overlap, to some degree, with those of certain other institutions. Nevertheless, the Court feels quite confident in holding that commercial banking, viewed collectively, has sufficient peculiar characteristics which negate reasonable interchangeability.[57]

None of this response goes to the question of how users of commercial-banking services consume them. Instead, it essentially takes the superficial marketing distinction as economically dispositive, despite the acknowledgment that economic substitutes for the constituent products exist. It is, of course, possible that, in PNB, the error was not outcome determinative; perhaps none of the overlap between commercial banks and other providers of commercial lending is significant enough to change the analysis. But this is not a rigorous defense of the notion.

In a few cases, a more rigorous econometric analysis has been used to establish the viability of cluster markets. Consider, for example, the FTC’s successful challenge of the proposed Penn State Hershey Medical Center/Pinnacle Health System merger.[58] At issue there were the likely effects of a merger for certain services provided by general acute care (GAC) hospitals—that is, a range or “cluster” of services sold to commercial health plans in a defined geographic area covering roughly four counties in central Pennsylvania. Two small community hospitals offered some of the same acute care services, and various clinics and group practices provided some of the primary and secondary care services in the cluster.

At the same time, there was evidence that commercial health plans needed to negotiate for coverage over a range of GAC services that other providers could not offer, and that the merging parties competed on price in such negotiations with commercial health plans. Copious econometric evidence—analysis of price data and patient-draw data—substantiated the FTC’s market definition, bolstered by an amicus brief filed by more than three dozen experts in antitrust, competition, and health-care economics.[59]

All of this supported the FTC’s argument that the provision of GAC services constituted a single “cluster market”—and the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, overturning a flawed geographic-market definition initially adopted by the district court.[60] That is, the agency didn’t merely waive its hands at an impression of ways that certain hospital services were similar to each other; rather, it provided detailed economic analysis of the price competition at issue for a specific range of GAC hospital services.

Notably, in that case, there were specific, identifiable consumers—commercial health plans—that were negotiating prices for a diverse “cluster” of GAC services. An individual patient will not, we hope, need to shop for oncology, cardio-thoracic surgery, a hip replacement, and ob-gyn services at the same time. But a health plan typically considers all of those and more. The same dynamic is not, of course, applicable in the Amazon case.

Perhaps the best example of the rigorous defense of cluster markets came in the first Staples/Office Depot merger matter, where ordinary-course documents played a role in the FTC’s review, but were by no means core to the staff’s analysis.[61] The FTC Bureau of Economics applied considerable econometric analysis of price data to establish that office superstore chains constrained each other’s pricing in a way that other vendors of office supplies did not.[62] That analysis of price effects (as evidence of likely merger effects and as evidence on behalf of the FTC’s market definition) is not apparent in the district court’s opinion enjoining the transaction.[63] But it figured heavily in the FTC’s presentation of the case and, presumably, in the commission’s internal decision to bring the case.

Two things are particularly notable about the cluster markets employed in Staples/Office Depot. First is that the exercise was undertaken at all. That is, it was assumed to be a crucial question whether other types of retailers (those with fewer products or catalog-only sales) constrained the pricing power of office-supply “superstores.” Second, the groupings of products analyzed were based on detailed analyses of pricing and price sensitivity over identified products, not superficial, subjective impressions of the market. The same was likewise the case in the Penn State Hershey hospital case mentioned above, and in other hospital-merger cases.

These types of evidence and analyses are simply not in evidence in the FTC’s case against Amazon—certainly not as they’ve presented it thus far.

B. The Problem of Cluster Markets in the FTC’s Amazon Complaint

The FTC’s approach to market definition in Amazon appears in sharp contrast with prior cases involving what were, arguably, valid cluster markets and somewhat narrow market definitions.

Although the Amazon case is only at the complaint stage, of course, no factors or analysis similar to those adduced in the hospital and office-superstore cases discussed above are present in the FTC’s complaint against Amazon. Indeed, the complaint offers no evidence that the FTC considered the possibility that different products and different sellers would need to be considered separately (the FTC certainly saw no need to preemptively defend its clustering in the complaint). Instead—and consistent with the apparent assumption that Amazon and its particular characteristics are virtually unique—the complaint appears to assume that if Amazon offers a grouping of products, or if Amazon offers services to different types of sellers, this constitutes an economically rigorous “relevant market.” (Spoiler alert: It does not.)

Such an assumption would seem to need some defense. Certainly, a customer buying a bolt cutter will not consider buying a sneaker to be a reasonable alternative; it is clearly not on the basis of demand substitution that the FTC lumps these products together.[64] Instead, similar competitive conditions across products are implicit in the FTC’s alleged markets. But are competitive conditions sufficiently similar across products sold on Amazon to justify clustering them?

1. Buyer-side clustering

Conditions vary considerably across the broad swath of products sold on Amazon. For some products sold at online superstores, brick-and-mortar retailers are a much closer substitute. Conceivably, consumers may prefer buying shoes at a brick-and-mortar retailer so that they can try them on, making physical retail a closer substitute for sneakers than for, say, a toilet brush, where very few consumers will demand to try the brush for balance before buying it. And surely consumers may be more willing to buy well-established brands (Nike, Gucci, etc.) directly from the brand’s website than a lesser-known brand sold at an online superstore.

Furniture, for example, is bought and sold in vastly different ways than, say, batteries (by consumers with different preferences for service and timing, by retailers with different relationships with manufacturers, through different channels of distribution, etc.). Whatever the merits to consumers of bundling purchases together from an “online superstore,” it is likely the case that they far less often bundle furniture purchases with other purchases than they do batteries. And surely consumers far more often seek to buy furniture offline or after testing it out in person than they do batteries. Vertically integrated furniture stores like IKEA have certainly done much to “commoditize” the production and sale of furniture in recent decades, but the market remains populated mostly by independent furniture showrooms, traditional manufacturers, and catalog and decorator sales. The same cannot be said for batteries, of course.

It also seems unlikely that consumers purchase Amazon’s proffered products in bundles meaningfully distinct from those they purchase elsewhere. People shopping for kitchen pantry items may well bundle their purchases of these items together. But in the vast majority of cases, they can get that same bundle from a grocery store, even though the grocery store carries many fewer SKUs overall. There is no analog to commercial health plans negotiating prices for a particular “cluster” of hospital services in Amazon’s case—and even if there were, it is certain that any number of other stores can match the actual clusters in which people regularly buy products from Amazon.

2. Seller-side clustering

The problem of false clustering is even more acute on the seller side in the alleged “online marketplace services” market. Sellers on Amazon comprise at least two distinct types. On the one hand are brands and manufacturers that have a limited range of their own products to offer. These sellers are not resellers of others’ goods, but product creators or brands that use Amazon to sell “direct to consumer” the same sort of products they might otherwise have to sell through a retail intermediary. Within this group there is a further distinction between large, known brands and entrepreneurs selling a unique product (or maybe a few unique products) of their own creation out of their proverbial garage.[65]

On the other hand are retailers—resellers—that offer a wide range of products, none of which they manufacture themselves, but which they may purchase in bulk from manufacturers or offer through drop-shipping. The seller is an intermediary between the actual maker or seller of the product and the customer (in this case, marketing and reaching customers through another intermediary: Amazon). Here, again, there is a further distinction between intermediaries that are virtually invisible or interchangeable pass-throughs of others’ goods and those that attempt to add some value by establishing their own private-label brands or by acting as a trusted intermediary that offers a curated set of products.

Each of these types of sellers has a different demand for the various services bundled by Amazon, and a different set of available alternatives to Amazon. They often compete in different markets, have different relationships with manufacturers, and have differing sets of internal capacities necessitating the purchase of different services (or the purchase of different services in different relative quantities), and entailing a different ability to evaluate their need for different services and differing degrees of reliance on Amazon to complement their capacities. Moreover, the competitive ramifications of constraining each’s ability to sell on Amazon (or increasing the price to do so) is considerably different.

This last point is most obvious when considering the effect on drop-shippers of a possible increase in price on Amazon. What would be the competitive effects if a particular drop-shipper of, say, toilet paper were somehow precluded from Amazon, or harmed by using it? In that case, the seller is largely irrelevant (or worse—simply an additional source of markup). The relevant question is not whether a particular seller can profitably sell the product: “The antitrust laws… were enacted for ‘the protection of competition not competitors.’”[66] Rather, the relevant question is whether the manufacturer of the product can access consumers, and whether consumers can access competing sellers. In the case of toilet paper (or virtually anything else drop-shipped), the answer is manifestly yes. Drop shippers of Charmin could probably disappear completely from Amazon, and consumers would still be able to buy it at competitive prices from Amazon, among a host of competing options, and Proctor & Gamble would have no trouble reaching consumers.

3. Implications

The implication of all this is that it seems highly dubious that furniture and batteries (to take just one example) face similar enough competitive conditions across online superstores for them to be grouped together in a single “cluster market.” While there may be superficial similarities in the website or technology connecting buyers and sellers, the underlying economics of production, distribution, and consumption seem to vary enormously.

The complaint offers no evidence to support the assertion of similar competitive conditions; no analysis of cross-elasticities of demand or supply across product categories; and no empirical evidence that a price increase for, say, furniture, could be offset by increased sales of batteries. Nor does the complaint consider more granular markets—like furniture, or sporting goods, or books—that would better capture these critical differences.

Indeed, it’s quite possible that narrower markets would demonstrate that Amazon faces real competition in some areas but not others. Grouping disparate products together risks obscuring situations where market power—and thus potentially anticompetitive effects from Amazon’s conduct—might exist in some product spaces but not others. The failure to properly define the relevant market for antitrust analysis doesn’t inherently imply a particular outcome; it just means no outcome can properly be determined.

The FTC offers no defense for clustering beyond the mere fact that Amazon offers these varied products on its platform. Yet selling through a common intermediary hardly establishes that the underlying competition is sufficiently similar to warrant single-market treatment, let alone that common conduct toward sellers affects all products and sellers equally. If the FTC cannot empirically defend treating distinct products as competitively interchangeable, as transactional complements, or as having the same competitive conditions, its case may collapse under the weight of its own market gerrymandering.

IV. Out-of-Market Effects

This leaves a final question about the two markets defined in the complaint: can and should they really be considered separately, when conduct in each market has significant effects in the other? My colleagues and I intend to address this question more broadly and in more detail in the future (and, indeed, have already begun to do so[67]). For now, I will share a few tantalizing thoughts about this issue.

If Amazon’s practices vis-à-vis sellers cause the sellers to lower their prices, improve the quality of the products available through the marketplace, or otherwise lower costs and whittle down the seller’s profits, then consumers would benefit. Similarly, if Amazon’s practices with sellers improve the quality of consumers’ experience on its marketplace, then consumers would also benefit. The question is whether gain on one side should offset any harms on the other.

The FTC contends that the markets should be considered separately, despite acknowledging (and even trying to bolster its case with) the reality that the two sides of Amazon’s platform have important effects on each other:

Feedback loops between the two relevant markets further demonstrate the critical importance of scale and network effects in these markets. While the markets for online superstores and online marketplace services are distinct, an online superstore may operate an online marketplace and offer associated online marketplace services to sellers. As a result, the relationship and feedback loops between the two relevant markets can create powerful barriers to entry in both markets.[68]

Despite this, the FTC will likely contend that out-of-market efficiencies are not cognizable. That is, benefits to consumers in the online-superstore market that flow from harm in the online-marketplace-services market do not apply (i.e., harm is harm, and it doesn’t matter if it benefits someone else). This approach, however, presents some obvious problems.

If platforms undertake conduct to maximize the overall value of the platform (and not merely the benefits accruing to any one side in particular), it is inevitable that some decisions will impose constraints on some users in order to maximize the value for everyone. Indeed, the FTC attempts to disparage “Amazon’s flywheel” as a mechanism for exploiting its dominance.[69] For Amazon, meanwhile, that “flywheel” encompasses the importance of ensuring value on one side of the platform in order to increase its value to the other side:

A critical mass of customers is key to powering what Amazon calls its “flywheel.” By providing sellers access to significant shopper traffic, Amazon is able to attract more sellers onto its platform. Those sellers’ selection and variety of products, in turn, attract additional shoppers.[70]

But at times, maximizing the value of the platform may entail imposing constraints on sellers or buyers. Unfortunately, some of these practices are the precise ones the FTC complains of here. Limiting access to the “Buy Box” by sellers of products that are available for less elsewhere, for example, ensures that consumers pay less and builds Amazon’s reputation for reliability;[71] bundling Prime services may mean some consumers pay for services they don’t use in order to get fast shipping, but it also attracts more Prime customers, enabling Amazon to raise revenue sufficient to guarantee same-, one-, or two-day shipping and providing a larger customer base for the benefit of its sellers.[72]

The bifurcated market approach also conflicts with the Supreme Court’s holding in Ohio v. American Express.[73] In Amex, the Court held that there must be net harm to both sides of a two-sided market (like Amazon) before a violation of the Sherman Act may be found. And even the decision’s critics recognize the need to look at effects on both sides of the market (whether they are treated as a single market, as in Amex, or not).[74]

The complaint itself seems to provide enough fodder to suggest that Amazon’s marketplace should be treated as a two-sided market, which the Supreme Court defined as a “platform [that] offers different products or services to two different groups who both depend on the platform to intermediate them.”[75] The complaint is replete with allegations of a “feedback loop” between the two markets, and it does appear that the consumers depend on the sellers and vice versa.

The economic literature shows that two-sided markets exhibit interconnectedness between their sides. It would thus be improper to consider effects on only one side in isolation. Yet that is what artificially narrow market definitions facilitate—letting plaintiffs make out a prima facie case of harm in one discrete area. This selective focus then gets upended once defendants demonstrate countervailing efficiencies outside that narrow market.

But why define markets so narrowly if weighing interrelated effects is ultimately essential? Doing so seems certain to heighten false-positive risks. Moreover, cabining market definitions and then trying to “take account” of interdependencies is analytically incoherent. It makes little sense to start with an approach prone to missing the forest for the trees, only to try correcting the distorted lens part way into the analysis. If interconnectedness means single-market treatment is appropriate, the market definition should match from the outset.

But I think the FTC is aiming not for the most accurate approach, but for the one that (it believes) simply permits it to ignore procompetitive effects in other markets, despite its repeated acknowledgment of the “feedback loops” between them.[76] Certainly, FTC Chair Lina Khan is well aware of the possible role that Amex could play, and has even stated previously that she believes Amex does apply to Amazon.[77] Instead, the agency is hoping (incorrectly, I believe) that the Court’s decision in Amex won’t apply, and that its decisions in PNB and Topco will ensure that each market be considered separately and without allowance for “out-of-market” effects occurring between them.[78] Such an approach would make it much easier for the FTC to win its case, but would do nothing to ensure an accurate result.

The district court in Amex, in fact, took a similar approach (finding in favor of the plaintiffs), holding that the case involved “two separate yet complementary product markets.”[79] Citing Topco and PNB, the district court asserted that, “[a]s a general matter . . ., a restraint that causes anticompetitive harm in one market may not be justified by greater competition in a different market.”[80] Similarly, Justice Stephen Breyer, also citing Topco, concluded in his Amex dissent that a burden-shifting analysis wouldn’t incorporate consideration of both sides of the market: “A Sherman Act §1 defendant can rarely, if ever, show that a procompetitive benefit in the market for one product offsets an anticompetitive harm in the market for another.”[81]

Some scholars assert that PNB and Topco apply to preclude offsetting, “out-of-market” efficiencies in monopolization cases, but it is by no means clear that the PNB limitation applies in Sherman Act cases. As a matter of precedent, PNB applies only to mergers evaluated under the Clayton Act. And the claim that the Court in Topco has extended the holding in PNB to the Sherman Act rests (at best) on dicta.[82]

It is true that the Court limited Amex to what it called “transaction” markets.[83] But courts are almost certainly going to have to deal with interrelated effects that occur in less-simultaneous markets, and they will almost certainly have to do so either by extending Amex’s single-market approach, or by accepting out-of-market efficiencies in one market as relevant to the antitrust analysis of an ostensibly distinct market on the other side of the platform. The FTC’s Amazon complaint presents precisely this dynamic.

Legal doctrine aside, ignoring benefits in one interconnected market while focusing on harms in another will lead to costly overdeterrence of procompetitive conduct.

Indeed, the FTC’s complaint identifies not just ambiguous conduct (conduct that may constrain one side but benefit the other side and the platform overall), but it points to the very act of providing benefits to consumers as a means of harming competition.[84]

What if Amazon makes it harder for new entrants on the “marketplace” side to enter profitably, because it offers benefits on the consumer side that most competitors can’t match? The FTC would have you believe that is a harm, full stop, because of the seller-side effect. But that would also effectively mean that simply increasing efficiency and lowering prices would amount to harm, because it would also make it harder for new entrants to match Amazon. How can conduct that provides a clear benefit to consumers constitute an antitrust harm?[85]

In essence, the FTC maintains this illogical position by cordoning off the two sides of Amazon’s platforms into separate markets and then asserting that benefits in one cannot justify “harms” in the other, despite recognizing the close interrelatedness between the two markets:

Sellers who buy marketplace services from Amazon provide much of the product selection that helps Amazon attract and keep its shoppers. As more shoppers turn to Amazon for its product selection, more sellers use its platform to gain access to its ever-expanding consumer base, which attracts more shoppers, and so on. . . . The interplay between Amazon’s shoppers and sellers increases barriers to new entry and expansion in both relevant markets and limits existing rivals’ ability to compete. In this way, scale builds on itself, and is cumulative and self-reinforcing.[86]

This is artificial and nonsensical. What Amazon does is maximize the value of the platform to the benefit of all users, on net. That some of those benefits accrue at certain times to only one set of users cannot be taken to undermine the value of Amazon’s overall, long-term platform-improving conduct.

Finally, it is worth noting that, even where nominal market distinctions across platform users have been argued by plaintiffs and upheld by courts, analysis of anticompetitive effects has generally turned to out-of-market effects.

Consider the famous case of Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp. In that case, analyzing the competitive effect of the defendant’s conduct regarding access by a competitor to an “all Aspen” ski pass required looking at effects in the output market for downhill skiing, as well as the input market for mountain access needed to provide those tickets.[87] Indeed, as the Court noted, “[t]he question whether Ski Co.’s conduct may properly be characterized as exclusionary cannot be answered by simply considering its effect on Highlands. In addition, it is relevant to consider its impact on consumers and whether it has impaired competition in an unnecessarily restrictive way.”[88] If Aspen Skiing were evaluated as the FTC seeks in this case, there would be two distinct markets at issue, and harm could be proven by assessing the effect on the input market alone, regardless of the effect on consumers.

Indeed, especially where vertically related markets are involved (which is, of course, how the two sides of Amazon’s platform are related), courts have recognized that weighing effects on competition requires a cross-market perspective across both upstream and downstream segments.

Conclusion

The FTC’s proposed market definitions in its case against Amazon exhibit several critical flaws that undermine the complaint. The alleged “online superstore” and “online marketplace services” markets are excessively narrow, excluding manifest competitors and alternatives. The FTC improperly groups together distinctly different products and sellers into questionable “cluster markets” without empirical evidence to support treating them as economically integrated. And the complaint arbitrarily cordons the two markets off from each other, despite acknowledging their interconnectedness, likely in a deliberate effort to avoid weighing out-of-market efficiencies and procompetitive effects flowing between them.

Ultimately, the burden lies with the FTC to defend these narrow market definitions as economically sound. But based on the limited information available thus far, the proposed markets appear to be gerrymandered to suit the FTC’s case, rather than reflective of actual competitive realities.

Whether deliberately tactical or not, the problems with the FTC’s market definition invite skepticism regarding the overall merits of the agency’s case. If the relevant markets prove indefensible upon fuller examination of the facts, the theory of harm in the case may well collapse. At a minimum, the FTC faces an uphill battle if its case indeed rests more on artful pleading than rigorous economics.

[1] Gregory J. Werden, Why (Ever) Define Markets? An Answer to Professor Kaplow, 78 Antitrust L.J. 729, 741 (2013) (emphasis added).

[2] See, e.g., Josh Sisco, The FTC Puts Your Lunch on Its Plate, Politico (Nov. 21, 2023), https://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/21/feds-probe-10b-deal-for-subway-sandwich-chain-00128268.

[3] Complaint, F.T.C., et al. v. Amazon.com, Inc., Case No. 2:23-cv-01495-JHC (W.D. Wa., Nov. 2, 2023) at ¶¶ 119-208, available at https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/1910129-1910130-amazoncom-inc-amazon-ecommerce (“Amazon Complaint”).

[4] Id. at ¶ 124.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Nike Store (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.nike.com.

[8] Wayfair (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.wayfair.com.

[9] E-Commerce Retail Sales as a Percent of Total Sales (ECOMPCTSA), FRED Economic Data (last updated Nov. 17, 2023), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ECOMPCTSA.

[10] Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶ 185.

[11] See, e.g., How Google Shopping Works, Google (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://support.google.com/faqs/answer/2987537; Shopify Official Website, Shopify (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.shopify.com/; Instagram Shopping, Instagram (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://business.instagram.com/shopping.

[12] See Geoffrey A. Manne & E. Marcellus Williamson, Hot Docs vs. Cold Economics: The Use and Misuse of Business Documents in Antitrust Enforcement and Adjudication, 47 Ariz. L. Rev. 609 (2005).

[13] For a discussion of this problem in the context of mergers (but with relevance to market definition in Section 2 cases), see Daniel J. Gilman, Brian Albrecht and Geoffrey A. Manne, The Conundrum of Out-of-Market Effects in Merger Enforcement, Truth on the Market (Jan. 16, 2024), https://truthonthemarket.com/2024/01/16/the-conundrum-of-out-of-market-effects-in-merger-enforcement.

[14] See Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶ 117.

[15] See id. at ¶ 163.

[16] See id. at ¶ 123 (“Online superstores offer shoppers a unique set of features”).

[17] See id. at ¶ 171. (“Other commercially available data, including recently reported statistics from eMarketer Insider Intelligence, a widely cited industry market research firm, confirms Amazon’s sustained dominance across this same set of companies, with an estimated market share of more than 82% of GMV in 2022.”).

[18] See Matthew Johnston, 10 Biggest Retail Companies, Investopedia (last updated May 8, 2023), https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/122415/worlds-top-10-retailers-wmt-cost.asp.

[19] Stephanie Chevalier, Market Share of Leading Retail E-Commerce Companies in the United States in 2023, Statista (Nov. 6, 2023), https://www.statista.com/statistics/274255/market-share-of-the-leading-retailers-in-us-e-commerce.

[20] See Matthew Johnston, supra note 18.

[21] See E-Commerce Retail Sales as a Percent of Total Sales, supra note 9.

[22] Werden, supra note 1, at 741.

[23] See Geoffrey A. Manne, Premium Natural and Organic Bulls**t, Truth on the Market (Jun. 6, 2007), https://truthonthemarket.com/2007/06/06/premium-natural-and-organic-bullst (“[E]conomically relevant market definition turns on demand elasticity among consumers who are often free to purchase products from multiple distribution channels, [and] a myopic focus on a single channel of distribution to the exclusion of others is dangerous.”).

[24] Hicks v. PGA Tour, Inc., 897 F.3d 1109, 1120-21 (9th Cir. 2018) (citing Newcal Indus., Inc. v. Ikon Office Sol., 513 F.3d 1038, 1045 (9th Cir. 2008)).

[25] See Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶¶ 128-33.

[26] Dick’s Sporting Goods (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.dickssportinggoods.com; REI Co-op Shop (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.rei.com; Bass Pro Shops (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.basspro.com/shop.

[27] Jackets, Columbia (last visited Dec. 10, 2023), https://www.columbia.com/c/outdoor-jackets-coats.

[28] See Columbia Coats & Jackets, Macy’s (last visited Dec. 10, 2023), https://www.macys.com/shop/womens-clothing/womens-coats/Brand/Columbia?id=269; Women’s Columbia Coats, Nordstrom (last visited Dec. 10, 2023), https://www.nordstrom.com/browse/women/clothing/coats-jackets?filterByBrand=columbia.

[29] See Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶¶ 148-59.

[30] See Daniela Coppola, Average Number of Products Bought Per Order Worldwide from January 2022 to December 2022, Statista (Feb. 1, 2023), https://www.statista.com/statistics/1363180/monthly-average-units-per-e-commerce-transaction.

[31] See Khadeeja Safdar, supra note 38.

[32] Google Product Discovery Statistics, Think with Google (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-strategies/search/google-product-discovery-statistics (“49% of shoppers surveyed say they use Google to discover or find a new item or product”). Also notable, “51% of shoppers surveyed say they use Google to research a purchase they plan to make online.” Product Research Statistics, Think with Google (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-strategies/search/product-research-search-statistics.

[33] See Danny Goodwin, 50% Of Product Searches Start on Amazon, Search Engine Land (May 16, 2023), https://searchengineland.com/50-of-product-searches-start-on-amazon-424451.

[34] Id.

[35] See Shopify (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.shopify.com; BigCommerce (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.bigcommerce.com.

[36] Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶ 198 (“SaaS providers’ services are not reasonably interchangeable with online marketplace services.”).

[37] See Brown Shoe Co., Inc. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 325 (1962) (“The outer boundaries of a product market are determined by the reasonable interchangeability of use or the cross-elasticity of demand between the product itself and substitutes for it.”).

[38] See, e.g., Khadeeja Safdar, Nike to Stop Selling Directly to Amazon, Wall Street J. (Nov. 13, 2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/nike-to-stop-selling-directly-to-amazon-11573615633.

[39] See Tomas Kacevicius (@intred), Twitter (Jun. 19, 2019, 7:05 PM), https://x.com/intred/status/1141527349193842688?s=20 (“[M]ore than 820K merchants are currently using #Shopify, making it the 3rd largest online retailer in the US.”).

[40] Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶ 199 (emphasis added).

[41] Id. at ¶ 5.

[42] See infra Section III.

[43] Juozas Kaziukenas, Google Shopping Is Again an E-Commerce Aggregator, Marketplace Pulse (Apr. 28, 2020), https://www.marketplacepulse.com/articles/google-shopping-is-again-an-e-commerce-aggregator.

[44] See Mohammad. Y, Instagram Commerce Statistics and Shopping Trends in 2023, OnlineDasher (last updated Sep. 19, 2023), https://www.onlinedasher.com/instagram-shopping-statistics.

[45] Id.

[46] Checkout on Instagram, Instagram for Business (last visited Dec. 7, 2023), https://business.instagram.com/shopping/checkout.

[47] See Shopify Fulfillment Network, Shopify (last visited Dec. 6, 2023), https://www.shopify.com/fulfillment; Outsourced Fulfillment, ShipBob (last visited Dec. 7, 2023), https://www.shipbob.com/product/outsourced-fulfillment.

[48] Promedica Health Sys., Inc. v. Fed. Trade Comm’n, 749 F.3d 559, 565 (6th Cir. 2014).

[49] Id. at 567.

[50] Id. (quoting 2B Areeda, Antitrust Law, ¶ 565c at 408).

[51] See EU Commission, Universal Music Group / EMI Music, Case No. COMP/M.6458, Decision, 21 September 2012, ¶¶ 141-58.

[52] See, e.g., In the Matter of HCA Healthcare/Steward Health Care System, FTC Docket No. 9410 (Jun. 2, 2022), available at https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/2210003-hca-healthcaresteward-health-care-system-matter.

[53] U.S. v. Philadelphia Nat. Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 356 (1963) (“PNB”) (“We agree with the District Court that the cluster of products (various kinds of credit) and services (such as checking accounts and trust administration) denoted by the term ‘commercial banking,’ composes a distinct line of commerce.”).

[54] Universal Music Group / EMI Music, supra note 51, at ¶ 141.

[55] PNB, 374 U.S. at 356 (emphasis added).

[56] United States v. Philadelphia National Bank, 201 F. Supp. 348, 361 (E.D. Pa. 1962).

[57] Id. at 363.

[58] In the Matter of Penn State Hershey Medical Center and Pinnacle Health System, FTC Docket No. 9368 (Dec. 7, 2015), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/151214hersheypinnaclecmpt.pdf.

[59] Consent Brief of Amici Curiae Economics Professors in Support of Plaintiffs/Appellants Urging Reversal, FTC v. Penn State Hershey Medical Center, et al., Case No. 16-2365 (3rd Cir., Jun. 8, 2016), available at https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Profile%20Files/Amicus%20Brief%20in%20re%20Hershey-Pinnacle%20Proposed%20Merger%206.2016_e38a4380-c58b-4bb4-aecd-26fc7431ecba.

[60] Fed. Trade Comm’n v. Penn State Hershey Med. Ctr., 838 F.3d 327 (3d Cir. 2016).

[61] Complaint, FTC v. Staples Inc. and Office Depot, Inc., Case No. 1:97CV00701 (D.D.C., Apr. 10, 1997), available at https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/9710008-staples-inc-office-depot-inc.

[62] See Orley Ashenfelter, David Ashmore, Jonathan B. Baker, Suzanne Gleason, & Daniel S. Hosken, Empirical Methods in Merger Analysis: Econometric Analysis of Pricing in FTC v. Staples, 13 Int’l J. Econ. of Bus. 265 (2006).

[63] F.T.C. v. Staples, Inc., 970 F. Supp. 1066 (D.D.C. 1997).

[64] And, for at least one court, this is the only basis on which a cluster market is appropriate. See Green Country Food v. Bottling Group, 371 F.3d 1275, 1284 (10th Cir. 2004) (“A cluster market exists only when the ‘cluster’ is itself an object of consumer demand.”) (citing Westman Comm’n Co. v. Hobart Int’l, Inc., 796 F.2d 1216, 1221 (10th Cir. 1986) (rejecting cluster market approach where cluster was not itself the object of consumer demand)).

[65] For example, successful Chinese food product startup Fly By Jing was started by one woman in 2018. She sells only her own products and does so not only on Amazon, but also on her own website and, among countless other places, Costco. See Fly By Jing Amazon Storefront, Amazon.com (last visited Dec. 8, 2023), https://www.amazon.com/stores/page/F2C02352-02C6-4804-81C4-DEA595C644DE; Fly By Jing (last visited Dec. 8, 2023), https://flybyjing.com/shop; Fly By Jing (@flybyjing), Instagram (Feb. 22, 2022), https://www.instagram.com/reel/CaSnvVzlkUW/ (“Sichuan Chili Crisp Now in Costco”).

[66] Brunswick Corp. v. Pueblo Bowl-O-Mat, Inc., 429 U.S. 477, 488 (1977) (quoting Brown Shoe, 370 U.S. at 320).

[67] See Gilman, Albrecht & Manne, supra note 13.

[68] Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶ 119.

[69] Id. at ¶ 9.

[70] Id. at ¶ 215.

[71] Id. at ¶ 269.

[72] Id. at ¶ 218.

[73] 138 S. Ct. 2274 (2018) (“Amex”).

[74] See, e.g., Michael Katz and Jonathan Sallet, Multisided Platforms and Antitrust Enforcement,127 Yale L.J. 2142 (2018). Katz and Sallet criticize the concept of treating both sides of a two-sided market in one relevant market: “Because users on different sides of a platform have different economic interests, it is inappropriate to view platform competition as being for a single product offered at a single (i.e., net, two-sided) price.” Id. at 2170. But they also contend that effects on both sides must be considered: “[In order] to reach sound conclusions about market power, competition, and consumer welfare, any significant linkages and feedback mechanisms among the different sides must be taken into account.” Id.

[75] Amex, 138 S. Ct. at 2280.

[76] See Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶¶ 119, 176, 179, 209, 215, & 217.

[77] Lina Khan, The Supreme Court Just Quietly Gutted Antitrust Law, Vox (Jul. 3, 2018), https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2018/7/3/17530320/antitrust-american-express-amazon-uber-tech-monopoly-monopsony (“On the surface, the Court’s language [in Amex] suggests that the special rule would apply to Amazon’s marketplace for third-party merchants.”).

[78] PNB, 374 U.S. 321; United States v. Topco Associates, Inc., 405 U.S. 596 (1972) (“Topco”).

[79] United States, et al. v. Am. Express Co., et al., 88 F. Supp. 3d 153, 171 (E.D.N.Y. 2015).

[80] Id., 88 F. Supp. 3d at 247 (citing Topco, 405 U.S. at 610; PNB, 374 U.S. at 370).

[81] Amex, 138 S. Ct. at 2303 (quoting Topco, 405 U.S. at 611).

[82] See Geoffrey A. Manne, In Defence of the Supreme Court’s ‘Single Market’ Definition in Ohio v American Express, 7 J. Antitrust Enf. 104, 115-17 (2019) (“The Court in Topco cited PNB in dictum, not for a doctrinal proposition relating to the operation of the rule of reason, but for a general, conceptual point about the asserted difficulty of courts adjudicating between conflicting economic rights. . . . Nowhere does the Court in Topco suggest that it is inappropriate within a rule-of-reason analysis to weigh out-of-market efficiencies against in-market effects.”).

[83] Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. at 2280 (“Thus, credit-card networks are a special type of two-sided platform known as a ‘transaction’ platform. The key feature of transaction platforms is that they cannot make a sale to one side of the platform without simultaneously making a sale to the other.”) (citations omitted).

[84] See, e.g., Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶ 222 (“Amazon’s restrictive all-or-nothing Prime strategy artificially heightens entry barriers because rivals and potential rivals cannot compete for shoppers . . . solely on the merits of their online superstores or marketplace services. Instead, they must enter multiple unrelated industries to attract Prime subscribers away from Amazon or incur substantially increased costs to convince Prime subscribers to sign up for a second shipping subscription or otherwise pay for shipping a second time. This substantial expense significantly constrains the number of firms who have any meaningful chance to compete against Amazon and raises the costs of any that even try. . . . Amazon’s restrictive strategy artificially heightens barriers to entry, such that an equally or even a more efficient or innovative rival would be unable to fully compete by offering a better online superstore or better online marketplace services.”).

[85] See Brian Albrecht, Is Amazon’s Scale a Harm?, Truth on the Market (Oct. 13, 2023), https://truthonthemarket.com/2023/10/13/is-amazons-scale-a-harm/.

[86] Amazon Complaint, supra note 3, at ¶¶ 214 & 216.

[87] In Aspen Skiing, the “jury found that the relevant product market was ‘[d]ownhill skiing at destination ski resorts,’” Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 472 U.S. 585, 596 n.20 (1985). The conduct at issue, however, occurred on the input side of the market.

[88] Id. at 605 (emphasis added).