Playing the Imitation Game in Digital Market Regulation – A Cautionary Analysis for Brazil

Introduction On 11 October 2022, João Maia (Federal Deputy, Partido Liberal) proposed Bill 2768/22 (“Bill 2768” or “Bill”) on digital market regulation.[1] Bill 2768 is . . .

Introduction

On 11 October 2022, João Maia (Federal Deputy, Partido Liberal) proposed Bill 2768/22 (“Bill 2768” or “Bill”) on digital market regulation.[1] Bill 2768 is Brazil’s response to global trends toward the ex-ante regulation of digital platforms, and was at least partially inspired by the EU’s Digital Markets Act (“DMA”).[2] In our contribution to the public consultation on Bill 2768 (“Consultation”),[3] however, we argue that Brazil should be wary of importing untested regulation into its own, unique context. Rather than impulsively replicating the EU’s latest regulatory whim, Brazil should adopt a more methodical, evidence-based approach. Sound regulation requires that new rules be underpinned by a clear vision of the specific market failures they aim to address, as well as an understanding of the costs and potential unintended consequences. Unfortunately, Bill 2768 fails to meet these prerequisites. As we show in our response to the Consultation, it is far from clear that competition law in Brazil has failed to address issues in digital markets to the extent that would make sui generis digital regulation necessary. Indeed, it is unlikely that there are any truly “essential facilities” in the Brazilian digital market that would make access regulation necessary, or that “data” represents an unsurmountable barrier to entry. Other aspects of the Bill—such as the designation of Anatel as the relevant enforcer, the extremely low turnover thresholds used to ascertain gatekeeper status, and the lack of consideration given to consumer welfare as a relevant parameter in establishing harm or claiming an exemption—are also misguided. As it stands, therefore, Bill 2768 not only risks straining Brazil’s limited public resources, but also harming innovation, consumer prices, and the country’s thriving startup ecosystem.

Question 1

Identification of “essential facilities” in the universe of digital markets. Give examples of platform assets in the digital market operating in Brazil where at the same time: a) there are no digital platforms with substitute assets close to these assets b) these assets are difficult to duplicate efficiently at least close to the owning company c) without access to this asset, it would not be possible to operate in one or more markets, as it constitutes a fundamental input. Justify each of the examples given.

For the reasons we discuss below, it is unlikely that there are any examples of true “essential facilities” in digital markets in Brazil.

It important to define the meaning of “essential facility” precisely. The concept of essential facility is a state-of-the-art term used in competition law, which has been defined differently across jurisdictions. Still, the overarching idea of the essential facilities doctrines is that there are instances in which denial of access to a facility by an incumbent can distort competition. To demarcate between cases where denial of access constitutes a legitimate expression of competition on the merits from instances in which it indicates anticompetitive conduct, however, courts and competition authorities have devised a series of tests.

Thus, in the EU, the seminal Bronner case established that the essential facilities doctrine applies in Art. 102 TFEU cases when:

- The refusal is likely to eliminate all competition in the market on the part of the person requesting the service;

- The refusal is incapable of being objectively justified; and

- The service in itself is indispensable to carrying out that person’s business, i.e., there is no actual or potential substitute for the requested input.[4]

In addition, the facility must be genuinely “essential” to compete, not merely convenient.

Similarly, CADE has incorporated the essential facilities doctrine into Brazilian competition policy by imposing a duty to deal with competitors.[5]

The definition of “essential facilities” and, consequently, the breadth and limits of the essential facilities doctrine under Bill 2768/2022 (“Bill 2768”) should reflect tried and tested principles from competition law. There is no reason why essential facilities should be treated differently in “digital” markets, i.e., markets involving digital platforms, than in other markets. In this sense, we are concerned that the framing of Question 1 reveals an inconsistency that should be addressed before moving forward; namely, when a company’s assets are “difficult” to replicate efficiently, it is justified to force a competitor to grant access to those assets. This is misguided and could even produce the opposite of what Bill 2768 presumably aims to achieve.

As indicated above, the fundamental concept underpinning the essential facilities doctrine is that it applies to a product or service that is uneconomic or impossible to duplicate. Typically, this has applied to infrastructure, such as telecommunications or railways. For instance, expecting competitors to duplicate transport routes, such as railways, would be unrealistic — and economically wasteful. Instead, governments have often chosen to regulate these sectors as natural monopoly public utilities. Predominantly, this includes mandating access to all comers to such essential facilities under regulated prices and non-discriminatory conditions that make the activity of other companies viable and competitive—thus facilitating competition on a secondary market in situations in which competition might otherwise be impossible.

The government should ask itself to what extent this logic applies to so-called digital platforms, however.

Online search engines, for example, are not impossible or excessively difficult to replicate—nor is access to any one of them indispensable. Today, many search engines are on the market: Bing, Yandex, Ecosia, DuckDuckGo, Yahoo!, Google, Baidu, Ask.com, and Swisscows, among others.

More to the point, mere access to search engines isn’t really a problem. Rather, in most cases, those complaining about a search engine’s activity typically complain about access to the very first results, or they complain about the search engine prioritizing its own secondary-market services over those of the competitor. But this space is vanishingly scarce; there is no way for it to be allocated to all comers. Nor can it be allocated on neutral terms; by definition, a search engine must prioritize results.

Treating a search engine as an essential facility would generate problematic outcomes. For example, mandating non-discriminatory access to a search engine’s top results would be like requiring that a railroad offer service to all shippers at whatever time the shipper liked, regardless of railroad congestion, other shippers’ timetables, and the railroad’s optimization of its schedule. Not only would this be impossible, but it isn’t even required of traditional essential facilities.

Notably, while ranking high on a search engine results page is undoubtedly a boon for business, there are other ways of reaching customers. Indeed, as CADE ruled in a case concerning Google Shopping, even if the first page of Google’s result is relevant and important to ranked websites, it is not irreplaceable to the extent that there are other ways for consumers to find websites online. Google is not a mandatory intermediary for website access.[6] Moreover, as noted, search results pages must, by definition, discriminate in order to function correctly. Deeming them essential facilities would entail endless wrangling (and technically complicated determinations) to decide if the search engine’s prioritization decisions were “proper” or not.

Similarly, online retail platforms like Amazon and Mercado Livre are very successful and convenient, but sellers can use other methods to reach customers. For example, they can sell from brick-and-mortar stores or easily set up their own retail websites using myriad software-as-a-service (“SaaS”) providers to facilitate processing and fulfilling orders. Furthermore, the concurrent presence and success of Mercado Livre, B2W (Submarino.com, Americanas.com, Shoptime, Soubarato), Cnova (Extra.com.br, Casasbahia.com.br, Pontofrio.com), Magazine Louiza, and Amazon on the Brazilian market belies the claim that any one of these platforms is indispensable or irreplicable.[7]

Similar arguments can be made about the other digital platforms covered by Art. 6, paragraph II of Bill 2768. For example, WhatsApp may be by far the most popular interpersonal communication service in the country. Still, there are plenty of alternatives within easy (and mostly free) reach for Brazilian consumers, such as Messenger (62 million users), Telegram (30 million), Instagram (64 million), Viber (3 million), Hangouts (2 million), WeChat (1 million), Kik (500,000 users), and Line (1 million users). The sheer number of users of every app suggests that multi-homing is widespread.

In sum, while access to a particular digital platform may be convenient, especially if it is currently the most popular among users, it is highly questionable whether such access is essential. And, as Advocate General Jacobs noted in his opinion in Bronner, mere convenience does not create a right of access under the essential facilities doctrine.[8]

Recommendation: Bill 2768 should make it clear that the principles and requirements of “essential facilities” within the meaning of competition law apply in full to the duties and obligations contemplated in Art. 10 — and that the finding of an “essential facility” is a prerequisite to the imposition of any such duties or obligations.

Question 2

Is regulation necessary to guarantee access to the asset(s) of the example(s) from Question 1? What should such regulation guarantee so that access to the asset enables third parties to enter those digital markets?

Before considering whether regulation is necessary to guarantee access to assets of certain companies, the government should first consider whether guaranteeing any such access is necessary and legitimate. In our response to Question 1, we have argued that it is unlikely to be. If the government nevertheless decides to the contrary, the next logical question should be whether competition law, including the essential facilities doctrine itself, are sufficient to address any such alleged problems as are identified in Question 2.

Arguably, the best way to answer this question would be through the natural experiment of letting CADE bring cases against digital platforms — assuming it can construct a prima facie case in each instance — and seeing whether or not traditional competition law tools provide a viable solution and, if not, whether these tools can be sharpened by reforming Brazil’s competition law or whether new, comprehensive ex-ante regulation is needed.

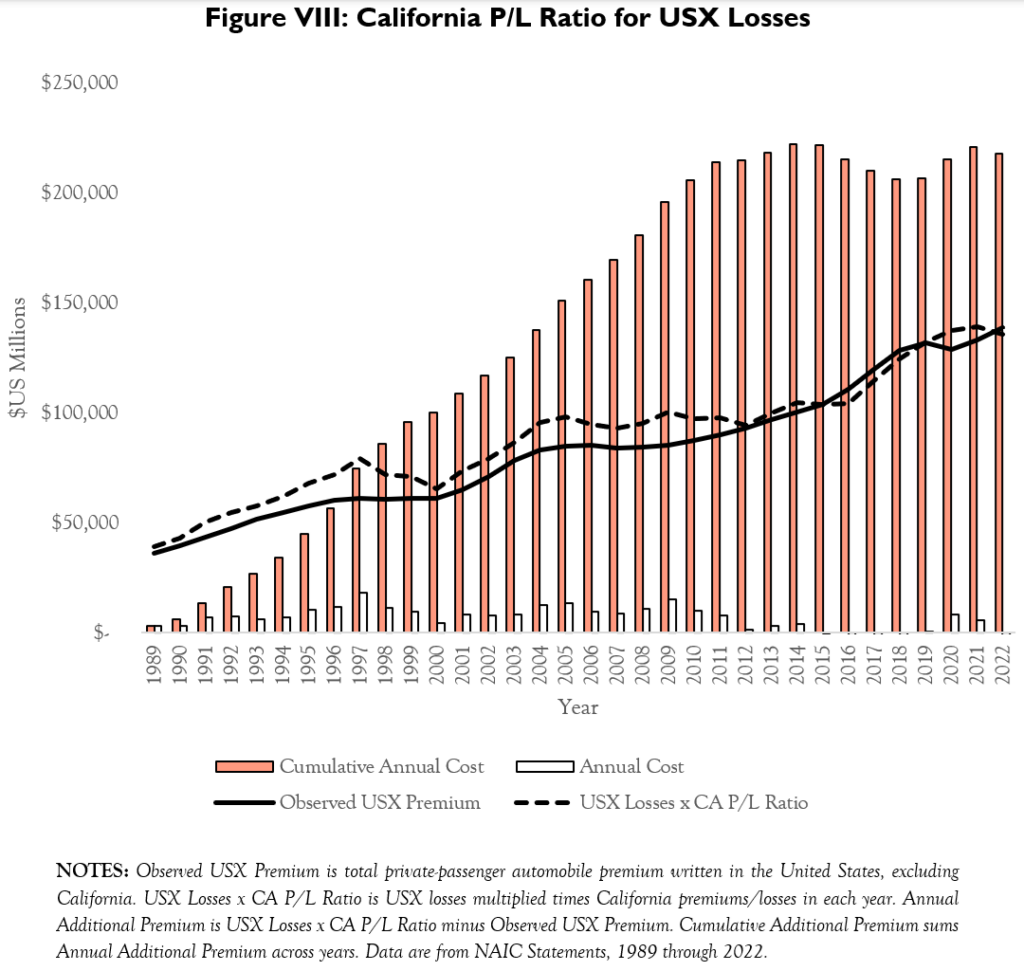

By comparison, the EU experimented with EU competition law before passing the DMA. In fact, most if not all the prohibitions and obligations of the DMA stem from competition law cases.[9] The EU eventually decided that it preferred to pass blanket ex-ante rules against certain practices rather than having to litigate through competition law. Whether or not this was the right decision is up for debate, but one thing is certain: The EU tried its competition toolkit extensively against digital platforms before learning from the outcomes and deciding it needed to be complemented with a new set of broader, enforcer-friendly, bright-line rules.

By contrast, Brazil has initiated only a handful of antitrust cases against digital platforms. According to numbers published by CADE,[10] CADE has reviewed 233 merger cases related to digital platform markets between 1995 and 2023 and, regarding unilateral conduct (monopolization cases)—those most relevant for the discussion on Bill 2768—opened 23 conduct cases. Regarding those 23 cases, 9 are still being investigated, 11 were dismissed, and only 3 were settled by the signature of a Cease-and-Desist Agreement (TCC). In this sense, only 3 cases (TCCs) out of 23 could be said to have been, to some extent, “condemned”. It is questionable whether these cases provide the sort of evidence of the existence of intrinsic competition problems in the eight service markets identified in Art. 6, paragraph II of Bill 2768 that would justify new, “sector-specific” access rules.[11]

In fact, the recent entry of companies into many of those markets suggests that the opposite is closer to the truth. There are numerous examples of entry in a variety of digital services, including the likes of TikTok, Shein, Shopee, and Daki, to name just a few.

Serious problems can arise when products that are not essential facilities are treated as such, of which we name two.

First, over-extending the essential facilities doctrine can encourage free riding.[12] This is not what the essential facilities doctrine, properly understood, aims to achieve, nor what it should be used for:

Consequently, the [European Court of Justice] implies that the [essential facilities doctrine] is not designed for the convenience of undertakings to free ride dominant undertakings, but only for the necessity of survival on the secondary market in situations where there are no effective substitutes.[13]

Why develop a competing online retail platform when access to Mercado Livre or Amazon is guaranteed by law? Free riding can discourage investments from third companies and targeted “gatekeepers,” especially in the development and improvement of competing business platforms (or alternative business models that are not exact replicas of existing platforms). Contrary to the stated goals of Bill 2768, this could further entrench incumbents, as the ability to free ride on others’ investments incentivizes companies to pivot away from contesting incumbents’ core markets to acting as complementors in those markets.

Indeed, a serious—and underappreciated—concern is the cost of excessive risk-taking by companies that can rely on regulatory protections to ensure continued viability even when it is not warranted.

Businesses must develop their business models and operate their businesses in recognition of the risk involved. A complementor that makes itself dependent upon a platform for distribution of its content does take a risk. Although it may benefit from greater access to users, it places itself at the mercy of the other — or at least faces great difficulty (and great cost) adapting to unanticipated platform changes over which it has no control. This is a species of the “asset specificity” problem that animates much of the Transaction Cost Economics literature.[14]

But the risk may be a calculated one. Firms occupy specialized positions in supply chains throughout the economy, and they make risky, asset-specific investments all the time. In most circumstances, firms use contracts to allocate both risk and responsibility in a way that makes the relationship viable. When it is too difficult to manage risk by contract, firms may vertically integrate (thus aligning their incentives) or simply go their separate ways.

The fact that a platform creates an opportunity for complementors to rely upon it does not mean that a firm’s decision to do so — and to do so without a viable contingency plan — makes good business sense. In the case of the comparison-shopping sites at issue in the EU’s Google Shopping decision,[15] for example, it was entirely predictable that Google’s algorithm would evolve. It was also entirely predictable that it would evolve in ways that could diminish or even eviscerate their traffic. As one online marketing expert put it, “counting on search engine traffic as your primary traffic source is a bit foolish, to say the least.”[16]

Providing guarantees (which is what a “gatekeeper” access rule accomplishes) in this situation creates a significant problem: Protecting complementors from the inherent risk in a business model in which they are entirely dependent upon another company with which they have no contractual relationship is at least as likely to encourage excessive risk taking and inefficient over-investment as it is to ensure that investment and innovation are not too low.[17]

Second, granting companies and competitors access to goods or services except in the very few and narrow cases[18] in which access to such goods and services is truly essential to sustain competition on the market sends platforms the wrong message. The message is that, after being encouraged to compete, successful companies will be punished for thriving. This is contrary to the spirit of competition law and the principle of free competition, which Bill 2768 should be careful not to eviscerate. As the great U.S. jurist Learned Hand observed in U.S. v. Aluminum Co. of America: “The successful competitor, having been urged to compete, must not be turned upon when he wins.”[19]

Furthermore, forcing companies to do business with third parties is at odds with the principle that, unless a violation of antitrust law can be ascertained, companies should be free to do business with whomever they choose.[20] Indeed, it is a cornerstone of the free market economy that “the antitrust laws [do] not impose a duty on [firms] . . . to assist [competitors] . . . to ‘survive or expand.’”[21]

Question 3

Describe cases in digital markets where there is at least one other company with substitute assets close to these assets of the main company, but none of the digital platforms that hold the asset provide access to it. In other words, even if there is more than one asset in the market, there is still a problem of accessing the asset. How could Bill 2768/2022, especially its article 10, be improved to improve access to essential supplies?

We are aware of no such cases.

Question 4

Describe cases in which the ownership of data in digital markets creates a barrier to entry that makes it very difficult or even impossible for incumbent digital platforms to enter the market. How could Bill 2768/2022 mitigate this problem, reducing the barrier to entry represented by access to data?

The extent to which data represents a barrier to entry is, in our opinion, vastly overstated. Bill 2768 should not assume that data is a barrier to entry and should assess claims to the contrary critically — especially if it intends to build a new, comprehensive regulatory regime on that assumption.[22]

In a nutshell, theories of “data as a barrier to entry” make the assertion that online data can amount to a barrier to entry, insulating incumbent services from competition and ensuring that only the largest providers thrive. This data barrier to entry, it is alleged, can then allow firms with monopoly power to harm consumers, either directly through “bad acts” like price discrimination, or indirectly by raising the costs of advertising, which then get passed on to consumers.[23]

However, the notion of data as an antitrust-relevant barrier to entry is more supposition than reality.

First, despite the rush to embrace “digital platform exceptionalism,” data is useful to all industries. “Data” is not some new phenomenon particular to online companies. It bears repeating that offline retailers also receive substantial benefit from, and greatly benefit consumers by, knowing more about what consumers want and when they want it. Through devices like coupons, membership discounts and loyalty cards (to say nothing of targeted mailing lists and the age-old practice of data mining check-out receipts), brick-and-mortar retailers can track purchase data and better serve consumers. Not only do consumers receive better deals for using them, but retailers know what products to stock and advertise and when and on what products to run sales.[24]

Of course, there are a host of other uses for data, as well, including security, fraud prevention, product optimization, risk reduction to the insured, knowing what content is most interesting to readers, etc. The importance of data stretches far beyond the online world, and far beyond mere retail uses more generally. To describe any one company as having a monopoly on data is therefore mistaken.

Second, it is not the amount of data that leads to success, but how that data is used to craft attractive products or services for users. In other words: information is important to companies because of the value that can be drawn from it, not for the inherent value of the data itself. Thus, many companies that accumulated vast amounts of data were subsequently unable to turn that data into a competitive advantage to succeed on the market. For instance, Orkut, AOL, Friendster, Myspace, Yahoo! and Flicker — to name a few — all gained immense popularity and access to significant amounts of data, but failed to retain their users because their products were ultimately lackluster.

Data is not only less important than what can be drawn from it, but data is also less important than the underlying product it informs. For instance, Snapchat created a challenger to Facebook so successfully (and in such a short time) that Facebook attempted to buy it for $3 billion (Google offered $4 billion). But Facebook’s interest in Snapchat was not about its data. Instead, Snapchat was valuable — and a competitive challenge to Facebook — because it cleverly incorporated the (apparently novel) insight that many people wanted to share information in a more private way.

Relatedly, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Yelp, TikTok (and Facebook itself) all started with little (or no) data but nevertheless found success. Meanwhile, despite its supposed data advantages, Google’s attempt at social networking, Google+, never caught up to Facebook in terms of popularity to users (and thus not to advertisers either) and shut down in 2019.

At the same, it is not the case that the alleged data giants — the ones supposedly insulating themselves behind data barriers to entry — actually have the type of data most relevant to startups anyway. As Andres Lerner has argued, if you wanted to start a travel business, the data from Kayak or Priceline (or local Decolar.com) would be far more relevant.[25] Or if you wanted to start a ride-sharing business, data from cab companies would be more useful than the broad, market-cross-cutting profiles Google and Facebook have. Consider companies like Uber and 99 that had no customer data when they began to challenge established cab companies that did possess such data. If data were really so significant, they could never have competed successfully. But Uber and 99 have been able to effectively compete because they built products that users wanted to use — they came up with an idea for a better mousetrap. The data they have accrued came after they innovated, entered the market, and mounted their successful challenges — not before.

Complaints about data facilitating unassailable competitive advantages thus have it exactly backwards. Companies need to innovate to attract consumer data, otherwise consumers will switch to competitors (including both new entrants and established incumbents). As a result, the desire to make use of more and better data drives competitive innovation, with manifestly impressive results: The continued explosion of new products, services and other apps is evidence that data is not a bottleneck to competition but a spur to drive it.

Third, competition online is (metaphorically—but not by much) one click or thumb swipe away. That is, barriers to entry and switching costs are low. Indeed, despite the alleged prevalence of data barriers to entry, competition online continues to soar, with newcomers constantly emerging and triumphing. The entry of online retailers and other digital platforms in Brazil is a case in point (See Questions 1 and 2). This suggests that the barriers to entry are not so high as to prevent robust competition.

Again, despite the supposed data-based monopolies of Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple, and others, there exist powerful competitors in the markets they compete in:

- If consumers want to make a purchase, they are more likely to do their research on Mercado Livre or Amazon than Google or Facebook, even with Facebook’s launch of Facebook Marketplace.

- Google flight search has failed to seriously challenge — let alone displace — its competitors, as critics feared. Decolar.com, Kayak, Expedia, and the like remain the most prominent travel search sites — despite Google having literally purchased ITA’s trove of flight data and data-processing acumen.

- ChatGPT, one of the most highly valued startups today, is now a serious challenger to traditional search engines.

- TikTok has rapidly risen to challenge popular social media apps like Instagram and Facebook.

Even assuming for the sake of argument that data creates a barrier to entry, there is little evidence that consumers cannot easily switch to a competitor. While there are sometimes network effects online, like with social networking, history still shows that people will switch. Myspace was considered a dominant network until it made a series of bad business decisions, and users ended up on Facebook instead; Orkut had a similar fate. Similarly, Internet users can and do use Bing, DuckDuckGo, Yahoo!, and a plethora of more specialized search engines on top of and instead of Google, and increasingly also turn to other ways to find information online (such as searching for a brand or restaurant directly on Instagram or TikTok, or asking ChatGPT a question). In fact, Google itself was once an upstart new entrant that replaced once-household names like Yahoo! and AltaVista.

Fourth, access to data is not exclusive. Data is not like oil. If, for example, Petrobras drills and extracts oil from the ground, that oil is no longer available to other companies. Data is not finite in the same way. Google knowing someone’s birthday doesn’t limit the ability of Facebook to know the same person’s birthday, as well. While databases may be proprietary, the underlying data is not. And what matters more than the data itself is how well it is analyzed (see first point). Because data is not exclusive like oil, any attempt to force the sharing of data in an attempt to help competitors creates a free-riding problem. Why go through the work of collecting valuable data on customers to learn what they want so you can better serve them when regulation mandates that Apple effectively give you the data?

In conclusion, the problem with granting competitors access to data is that data is a consequence of competition, not a prerequisite for it. Thus, rather than enhancing their ability to compete, “gifting” competitors the fruits of others’ successful attempts at competition risks destroying both groups’ incentives to design attractive products to accrue such data in the first place. By reversing the competition-data causality, Bill 2768 ultimately risks inadvertently stifling the same competition that it purportedly seeks to bolster.

Question 5

Cite cases in which a company in the digital market in Brazil used third-party data because of its characteristic as an essential input provider, harming the third party competitively?

We are not aware of any such cases.

However, the framing of this question should be clear about what is meant by “harming a third party competitively.” The use of third-party data is a key driver of competition. Even if competitors are “harmed” as a result, they are harmed only insofar as they do not match the price or quality offered by the platform.

Competition is, to a large extent, driven by the use of knowledge of rivals’ products — including their price, quality, quantity, and how they are sold and presented to consumers. In fact, the model of perfect competition largely assumes that all the products on the market are homogeneous (even if this is rarely borne out in practice). The use of third-party data to match and beat competitor’s offerings can be seen as a modern expression of this dynamic. Indeed, as we have written before:

We cannot assume that something is bad for competition just because it is bad for certain competitors. A lot of unambiguously procompetitive behavior, like cutting prices, also tends to make life difficult for competitors. The same is true when a digital platform provides a service that is better than alternatives provided by the site’s third-party sellers. […].

There’s no doubt this is unpleasant for merchants that have to compete with these offerings. But it is also no different from having to compete with more efficient rivals who have lower costs or better insight into consumer demand. Copying products and seeking ways to offer them with better features or at a lower price, which critics of self-preferencing highlight as a particular concern, has always been a fundamental part of market competition—indeed, it is the primary way competition occurs in most markets.[26]

Any per se prohibition of the use of third-party data would preclude digital platforms from using data to improve their product offering in ways that could benefit consumers.

Recommendation: Assuming that competition law and IP law are not up to the task of curbing abuses of third-party data, Bill 2768 should ensure that such prohibitions are tailor-made to cover conduct that has no other rational explanation other than seeking to exclude a competitor. It should not capture uses of third-party data that drives competition and benefit consumers, even if this results in the exit of a competitor from the market.

Question 6

Describe cases in which a difficulty in interoperability with a company’s systems makes it very difficult or impossible to enter one or more digital markets. How could Bill 2768/2022 mitigate this problem, reducing the barrier to entry represented by lack of interoperability?

We are not aware of any such cases.

However, when considering potential interoperability mandates, the government should be aware of the risks and trade-offs that come with such measures, especially in terms of safety, security, and privacy (see Question 8 for a more detailed discussion).

Question 7

The European Digital Market Act (DMA) chose to implement absolute prohibitions (per se) on some conduct in digital markets, such as self-preferencing, among others. Bill 2768/2022, on the other hand, chose not to do any prohibited conduct ex ante. Should there be one or more conducts with absolute prohibitions (per se) in Bill 2768/2022? Why? Please propose wording, explaining where in the bill it would be located?

No, there should not be absolute prohibitions on these sorts of conduct, especially without substantive experience suggesting that such conduct is always or almost always harmful and largely irredeemable (in this item, we answer the question in general terms; please see Question 8 for a discussion of why particular conduct (e.g., self-preferencing) should not be prohibited).

Regardless of the harm to the business of the targeted companies, overly broad prohibitions (or mandates) can harm consumers by chilling procompetitive conduct and discouraging innovation and investment, especially when no showing of harm is required and the law is not amenable to efficiencies arguments (like in the case of the DMA). The fact that such prohibitions apply to vastly different markets (for example, cloud services have little to do with search engines) regardless of context is also a sure sign that they are overly broad and poorly designed.

In fact, there are indications that where the DMA has been introduced, it has delayed the advance of technology. For example, Google’s “Bard” AI was rolled out later in Europe due to the EU’s uncertain and strict AI And privacy regulations.[27] Similarly, Meta’s “Threads” is not available in the EU precisely due to the constraints imposed by the DMA and the EU’s data privacy regulation (GDPR).[28] Elon Musk, X’s (formerly Twitter) CEO, has indicated that the cost of complying with EU digital regulations, such as the DSA, could prompt it to exit the European market.[29] Recently, Microsoft delayed the European rollout of its new AI, “Copilot,” because of the DMA.[30]

Apart from capturing pro-competitive conduct that benefits consumers and freezing technology in time (which would ultimately exacerbate the technological chasm between more and less advanced countries), rigid per se rules could also capture many budding companies that cannot be considered “gatekeepers” by any stretch of the imagination. This risk is especially real in the case of Brazil given the extremely low threshold for what constitutes a “gatekeeper” enshrined in Article 9 (R$70 million, or approximately USD$14 million). Thus, many Brazilian unicorns could, either immediately or in the near future, be captured by the new, restrictive rules, which could stunt their growth and chill innovative products. Ultimately, this could imperil Brazil’s current status as “[Latin America’s] most established startup hub” and cast a shadow on what The Economist has referred to as the bright future of Latin American startups.[31]

The list of harmed companies could include some of Brazil’s most promising unicorns, such as:

- 99 (transport app)

- Neon Bank (digital bank)

- C6 Bank (digital bank)

- CloudWalk (payment method)

- Creditas (lending platform)

- Ebanx (payment solutions)

- Facily (social commerce)

- com (road freight)

- Gympass (gym aggregator and corporate benefits)

- Hotmart (platform for selling digital products)

- iFood (delivery)

- Loft (real estate platform)

- Loggi (logistics)

- Mercado Bitcoin (cryptocurrency broker)

- Merama (e-commerce)

- Madeira Madeira (home and decoration products store)

- Nubank (bank)

- Olist (e-commerce)

- Wildlife Studios (game developer)

- Quinto Andar (rental platform)

- Vtex (technology and digital commerce)

- Unico (biometrics)

- Dock (infrastructure)

- Pismo (technology for payments and banking services)[32]

Question 8

Would there be behaviors in digital markets that would have a high potential to entail competitive problems, but which can be justified as generating greater efficiency for companies, transactions, and markets? Give examples of these behaviors? How should these behaviors be treated in Bill 2768/2022? In particular, a “reversal of the burden of proof” would be appropriate, in which such conduct would presumably be anti-competitive, but would it be appropriate to authorize a defense of digital platforms based on these efficiencies? Should these behaviors be considered not prohibited per se, but as a “reversal of the burden of proof” in Bill 2768/2022?

There are certain types of behavior in digital markets that have been targeted by ex-ante regulations but which are nevertheless capable of, or even central to, delivering significant procompetitive benefits. It would be unjustified and harmful to subject such conduct to per se prohibitions or to reverse the burden of proof. Instead, this type of conduct should be approached neutrally, and examined on a case-by-case basis.[33]

A. Self-Preferencing

Self-preferencing occurs when a company gives preferential treatment to one of its own products (presumably, this type of behavior could be caught by Art. 10, paragraph II of Bill 2768). An example would be Google displaying its shopping service at the top of search results ahead of alternative shopping services. Critics of this practice argue that it puts dominant firms in competition with other firms that depend on their services, and this allows companies to leverage their power in one market to gain a foothold in an adjacent market, thus expanding and consolidating their dominance. However, this behavior can also be procompetitive and beneficial to users.

Over the past several years, a growing number of critics have argued that big tech platforms harm competition by favoring their own content over that of their complementors. Over time, this argument against self-preferencing has become one of the most prominent among those seeking to impose novel regulatory restrictions on these platforms.

According to this line of argument, complementors would be “at the mercy” of tech platforms. By discriminating in favor of their own content and against independent “edge providers,” tech platforms cause “the rewards for edge innovation [to be] dampened by runaway appropriation,” leading to “dismal” prospects “for independents in the internet economy—and edge innovation generally.”[34]

The problem, however, is that the claims of presumptive harm from self-preferencing (also known as “vertical discrimination”) are based neither on sound economics nor evidence.

The notion that platform entry into competition with edge providers is harmful to innovation is entirely speculative. Moreover, it is flatly contrary to a range of studies showing that the opposite is likely true. In reality, platform competition is more complicated than simple theories of vertical discrimination would have it,[35] and the literature establishes that there is certainly no basis for a presumption of harm.[36]

The notion that platforms should be forced to allow complementors to compete on their own terms, free of constraints or competition from platforms is a species of the idea that platforms are most socially valuable when they are most “open.” But mandating openness is not without costs, most importantly in terms of the effective operation of the platform and its own incentives for innovation.

“Open” and “closed” platforms are different ways of supplying similar services, and there is scope for competition between these alternative approaches. By prohibiting self-preferencing, a regulator might therefore close down competition to the detriment of consumers. As we have noted elsewhere:

For Apple (and its users), the touchstone of a good platform is not ‘openness,’ but carefully curated selection and security, understood broadly as encompassing the removal of objectionable content, protection of privacy, and protection from ‘social engineering’ and the like. By contrast, Android’s bet is on the open platform model, which sacrifices some degree of security for the greater variety and customization associated with more open distribution. These are legitimate differences in product design and business philosophy.[37]

Moreover, it is important to note that the appropriation of edge innovation and its incorporation into the platform (a commonly decried form of platform self-preferencing) greatly enhances the innovation’s value by sharing it more broadly, ensuring its coherence with the platform, incentivizing optimal marketing and promotion, and the like. Smartphones are now a collection of many features that used to be offered separately, such as phones, calculators, cameras and gaming consoles, and it is clear that the incorporation of these features in a single device has brought immense benefits to consumers and society as a whole. In other words, even if there is a cost in terms of reduced edge innovation, the immediate consumer welfare gains from platform appropriation may well outweigh those (speculative) losses.

Crucially, platforms have an incentive to optimize openness (and to assure complementors of sufficient returns on their platform-specific investments). This does not mean that maximum openness is optimal, however; in fact, typically a well-managed platform will exert top-down control where doing so is most important, and openness where control is least meaningful.[38]

But this means that it is impossible to know whether any particular platform constraint (including self-prioritization) on edge provider conduct is deleterious, and similarly whether any move from more to less openness (or the reverse) is harmful.

This is the situation that leads to the indeterminate and complex structure of platform enterprises. Consider the big online platforms like Google and Facebook, for example. These entities elicit participation from users and complementors by making access to their platforms freely available for a wide range of uses, exerting control over access only in limited ways to ensure high quality and performance. At the same time, however, these platform operators also offer proprietary services in competition with complementors or offer portions of the platform for sale or use only under more restrictive terms that facilitate a financial return to the platform.

The key is understanding that, while constraints on complementors’ access and use may look restrictive compared to an imaginary world without any restrictions, in such a world the platform would not be built in the first place. Moreover, compared to the other extreme — full appropriation (under which circumstances the platform also would not be built…) — such constraints are relatively minor and represent far less than full appropriation of value or restriction on access. As Jonathan Barnett aptly sums it up:

The [platform] therefore faces a basic trade-off. On the one hand, it must forfeit control over a portion of the platform in order to elicit user adoption. On the other hand, it must exert control over some other portion of the platform, or some set of complementary goods or services, in order to accrue revenues to cover development and maintenance costs (and, in the case of a for-profit entity, in order to capture any remaining profits).[39]

For instance, companies may choose to favor their own products or services because they are better able to guarantee their quality or quick delivery.[40] Mercado Livre, for instance, may be better placed to ensure that products provided by the ‘Mercado Envios logistics service are delivered in a timely manner compared to other services. Consumers may benefit from self-preferencing in other ways, too. If, for instance, Google were prevented from prioritizing Google Maps or YouTube videos in its search queries, it could be harder for users to find optimal and relevant results. If Amazon is prohibited from preferencing its own line of products on the marketplace, it may instead opt not to sell competitors’ products at all.

The power to prohibit the requiring or incentivizing of customers of one product to use another would enable the limiting or prevention of self-preferencing and other similar behavior. Granted, traditional competition law has sought to restrict the ‘bundling’ of products by requiring them to be purchased together, but to prohibit incentivization as well goes much further.

B. Interoperability

Another mot du jour is interoperability, which might fall under Art. 10, paragraph IV of Bill 2768. In the context of digital ex ante regulation, ‘interoperability’ means that covered companies could be forced to ensure that their products integrate with those of other firms. For example, requiring a social network to be open to integration with other services and apps, a mobile operating system to be open to third-party app stores, or a messaging service to be compatible with other messaging services. Without regulation, firms may or may not choose to make their software interoperable. However, Europe’s DMA and the UK’s prospective Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Bill (“DMCC”),[41] will allow authorities to require it. Another example is data ‘portability,’ which allows customers to move their data from one supplier to another, in the same way that a telephone number can be kept when one changes network.

The usual argument is that the power to require interoperability might be necessary to ‘overcome network effects and barriers to entry/expansion.’ However, the Brazilian government should not overlook that this solution comes with costs to consumer choice, in particular by raising difficulties with security and privacy, as well as having questionable benefits for competition. In fact, it is not as though competition disappears when customers cannot switch as easily as they turn on a light. Companies compete upfront to attract such consumers through tactics like penetration pricing, introductory offers, and price wars.[42]

A closed system, that is, one with comparatively limited interoperability, can help limit security and privacy risks. This can encourage use of the platform and enhance the user experience. For example, by remaining relatively closed and curated, Apple’s App Store gives users the assurance that apps will meet a certain standard of security and trustworthiness. Thus, ‘open’ and ‘closed’ ecosystems are not synonymous with ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ and instead represent two different product design philosophies, either of which might be preferred by consumers. By forcing companies to operate ‘open’ platforms, interoperability obligations could thus undermine this kind of inter-brand competition and override consumer choices.

Apart from potentially damaging user experience, it is also doubtful whether some of the interoperability mandates, such as those between social media or messaging services, can achieve their stated objective of lowering barriers to entry and promoting greater competition. Consumers are not necessarily more likely to switch platforms simply because they are interoperable. In fact, there is an argument to be made that making messaging apps interoperable in fact reduces the incentive to download competing apps, as users can already interact with competitors’ apps from the incumbent messaging app.

C. Choice Screens

Some ex-ante rules seek to address firms’ ability to influence user choice of apps through pre-installation, defaults, and the design of app stores (this could fall under Art. 10, paragraph II of Bill 2768). This has sometimes resulted in the imposition of requirements to provide users with ‘choice screens,’ for instance requiring users to choose which search engine or mapping service is installed on their phone. In this sense, it is important to understand the trade-offs at play here: choice screens may facilitate competition, but they may do so at the expense of the user experience, in terms of the time taken to make such choices. There is a risk, without evidence of consumer demand for ‘choice screens,’ that such rules impose the legislator’s preference for greater optionality over what is most convenient for users. Unless there is explicit public demand in Brazil for such measures, it would be ill-advised to implement a choice screen obligation.

D. Size and Market Power

In general, many of the prohibitions and obligations contemplated in ex-ante rules target incumbents’ size, scalability, and “strategic significance.”

It is widely claimed that because of network effects, digital markets are prone to ‘tipping’ whereby when one producer gains a sufficient share of the market, it quickly becomes a complete or near-complete monopolist. Although they may begin as very competitive, these markets therefore exhibit a marked ‘winner takes all’ characteristic. Ex ante rules often try to avert or revert this outcome by targeting a company’s size, or by targeting companies with market power.

However, there are many investments and innovations that will – if permitted – benefit consumers, either immediately or in the longer term, but which may have some effect on enhancing market power, a companies’ size, or its strategic significance. Indeed, improving a firm’s products and thereby increasing its sales will often lead to increased market power.

Accordingly, targeting “size” or conduct which bolsters market power, without any accompanying evidence of harm, creates a serious danger of a very broad inhibition of research, innovation, and investment – all to the detriment of consumers. Insofar as such rules prevent the growth and development of incumbent firms, they may also harm competition, since it may well be these firms that – if permitted – are most likely to challenge the market power of other firms in other, adjacent markets. The cases of Disney, Apple, Amazon and Globo’s launch of video-on-demand services to compete with Netflix, and Meta’s introduction of ‘Threads’ as a challenge to Twitter (or ‘X’), appear to be an example. Here, per se rules that have the aim of prohibiting the bolstering of size or market power in one area may in fact prevent entry by one firm into a market dominated by another. In that case, policymaker action protects monopoly power. Therefore, a much subtler approach to regulation is required.

Bill 2768’s reference to Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness, which notoriously adopts a reductive “big is bad” ethos, suggests that it could be making a similarly flawed assumption.[43]

E. Conclusion

We do not think it is appropriate to reverse the burden of proof in any instances in the context of digital platforms. Without substantive evidence that such conduct causes widespread harm to a well-defined public interest (e.g., similar to cartels in the context of antitrust law), there is no justification for a reversal of the burden of proof, and any such reversal of the burden of proof risks undermining consumer benefits, innovation, and discouraging investment in the Brazilian economy for a justified fear that procompetitive conduct will result in fines and remedies. By the same token, we do think that where the appointed enforcer makes a prima facie case of harm, whether in the context of antitrust law or ex-ante digital regulation, it should also be prepared to address arguments related to efficiencies.

Question 9

Is there a need for a regulator? If so, which regulator would be better able to implement the regulation provided for in Bill 2768/2022? Anatel, CADE, ANPD, another existing or new regulator? Justify.

Despite the lack of clarity concerning the law’s goals and objectives, the rules proposed by Bill 2768 appear to be competition based, at least insofar as they seek to bolster free competition, consumer protection, and tackle “abuse of economic power” (Art. 4). Therefore, the agency best positioned to enforce it would, in principle, be CADE (the goals of Act 12.529/11, the Brazilian Competition Law, overlap significantly with those under Bill 2768). Conversely, there is a palpable risk that, in discharging its duties under Bill 2768, Anatel would transpose the logic and principles of telecommunications regulation to “digital” markets, which is misguided as these are two very different things.

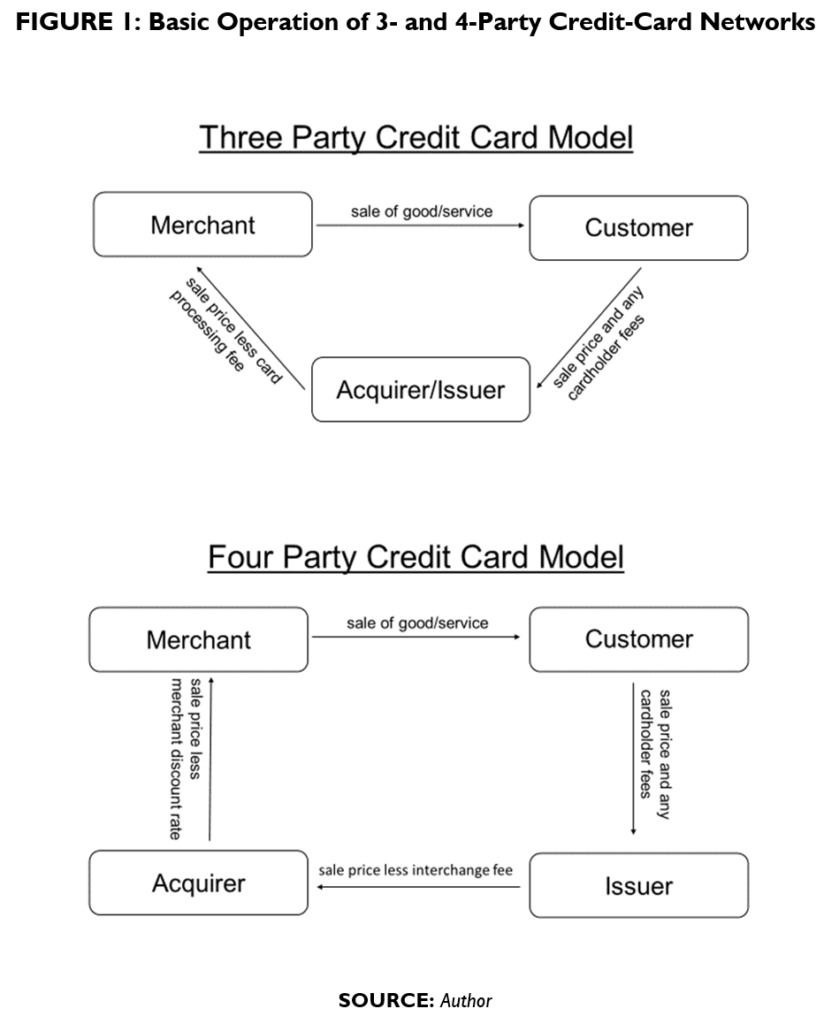

Not only are “digital” markets substantively different from telecommunications markets, but there is really no such thing as a clearly demarcated concept of “digital market.” For example, the digital platforms described in Art. 6, paragraph II of Bill 2768 are not homogenous, and cover a range of different business models. In addition, virtually every market today incorporates “digital” elements, such as data. Indeed, companies operating in sectors as divergent as retail, insurance, healthcare, pharma, production, and distribution have all been “digitalized.” Thus, an enforcer with a nuanced understanding of the dynamics of digitalization and, especially, the idiosyncrasies of digital platforms as two-sided markets, appears necessary. While CADE arguably lacks substantive experience with digital platforms, it is better placed to enforce Bill 2768 than Anatel because of its deep experience with the enforcement of competition policy.

Question 10

Do you think that there could be any risk of bis in idem between the regulator and the competition authority with the same conduct being analyzed by both?

Based on the EU experience, there is a risk of double jeopardy at the intersection of traditional competition law and ex-ante digital regulation.

By way of comparison, and as Giuseppe Colangelo has written, the DMA is grounded explicitly on the notion that competition law alone is insufficient to effectively address the challenges and systemic problems posed by the digital platform economy.[44] Indeed, the scope of antitrust is limited to certain instances of market power (e.g., dominance on specific markets) and of anti-competitive behavior. Further, its enforcement occurs ex post and requires extensive investigation on a case-by-case basis of what are often very complex sets of facts and may not effectively address the challenges to well-functioning markets posed by the conduct of gatekeepers, who are not necessarily dominant in competition-law terms — or so its proponents argue. As a result, regimes like the DMA invoke regulatory intervention to complement traditional antitrust rules by introducing a set of ex ante obligations for online platforms designated as gatekeepers. This also allows enforcers to dispense with the laborious process of defining relevant markets, proving dominance, and measuring market effects.

However, despite claims that the DMA is not an instrument of competition law, and thus would not affect how antitrust rules apply in digital markets, the regime does appear to blur the line between regulation and antitrust by mixing their respective features and goals. Indeed, the DMA shares the same aims and protects the same legal interests as competition law.

Further, its list of prohibitions is effectively a synopsis of past and ongoing antitrust cases, such as Google Shopping (Case T-612/17), Apple (AT.40437) and Amazon (Cases AT.40462 and AT.40703).[45] Acknowledging the continuum between competition law and the DMA, the European Competition Network (ECN) and some EU member states (self-anointed “friends of an effective DMA”) initially proposed empowering national competition authorities (NCAs) to enforce DMA obligations.[46]

Similarly, the prohibitions and obligations contemplated in Art. 10 of Bill 2768 could, in theory, all be imposed by CADE. In fact, CADE has investigated, and is still investigating, several large companies which would (likely) fall within the purview of Bill 2768, such as Google, Apple, Meta, (still under investigation) Booking.com, Decolar.com, Expedia and iFood (settled through case-and-desist agreements), and Uber (all investigations closed without penalties; following an economic study, CADE found that Uber’s entry benefitted consumers[47]). CADE’s past and current investigations against these companies already covered conducts that are targeted by the DMA and Bill 2768, such as refusal to deal, self-preferencing, and discrimination.[48] Existing competition law under Act 12.529/11, the Brazilian Competition Law, thus clearly already captures the sort of conduct which is included under Bill 2768. In addition, the requirement to use data “adequately” is likely covered by data protection regulation in Brazil (Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados, LGPD, Lei Federal Nº 13.709/2018).

The difference between the two regimes is that, while general antitrust law requires a showing of harm (even if potential) and exempts conduct with net benefits to consumers, Bill 2768 in principle does not. The only limiting principle to the prohibitions and obligations contained in Art. 10 Art. 11 (III) is the principle of proportionality — which is a general principle of constitutional law and should, in any case, apply regardless of Bill 2768. Thus, the only limiting principle of Art. 10, framed broadly, is redundant.

There is one additional complication. Bill 2768 pursues many (though not all) of the same objectives as Act 12.529/11. Insofar as these objectives are shared, it could lead to double jeopardy i.e., the same conduct being punished twice under slightly different regimes. But it could also produce contradictory results because, as pointed out above, the objectives pursued by the two bills are not identical. Act 12.529/11 is guided by the goals of “free competition, freedom of initiative, social role of property, consumer protection and prevention of the abuse of economic power” (Art. 1). To these objectives, Bill 2768 adds “reduction of regional and social inequalities,” and “increase of social participation in matters of public interest.” While it is true that these principles derive from Art. 170 of the Brazilian Constitution (“economic order”), the mismatch between the goals of Act 12.529/11 and Bill 2768 and their enforcing authorities is sufficient as to lead to situations in which conduct that is allowed or even encouraged under Act 12.529/11 is prohibited under Bill 2768. For instance, procompetitive conduct by a covered platform could nevertheless exacerbate “regional or social inequalities” because it invests heavily in one region, but not others. In a similar vein, safety, privacy, and security measures implemented by, say, an operator of an App Store, which would typically be considered beneficial for consumers under antitrust law,[49] could feasibly lead to less participation in discussions of public interest (assuming one could easily define the meaning of such a term).

Accordingly, Bill 2768 could fragment Brazil´s legal framework due to overlaps with competition law, stifle procompetitive conduct, and lead to contradictory results. This, in turn, is likely to impact legal certainty and the rule of law in Brazil, which could adversely affect Foreign Direct Investment.[50] Furthermore, coordination between CADE and Anatel is likely to be costly, if the latter ends up being the designated enforcer of Bill 2768. Brazil would essentially have two Acts pursuing the same or similar goals being implemented by two different agencies, with all the extra compliance and coordination costs that come with such duplicity.

Question 11

What is your assessment of the criteria of art. 9 of Bill 2768/2022? Should it be changed? By what criteria? Is it necessary to designate the essential service-to-service access control power holder?

This criterion seems arbitrary and, in any case, extremely low. There is no objective reason that would link “power to control access” with turnover. Furthermore, even if one admits, for the sake of argument, that turnover is a relevant indication of gatekeeper power, a R$70 million threshold would capture dozens, if not hundreds of companies active in a range of industries. This can lead to a situation in which a law that was initially — and purportedly — aimed at very specific “digital” firms, like Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, etc., ends up, by and large, covering a host of other, comparatively small firms, including some of Brazil’s most valuable unicorns (see Question 7). On the other hand, it is also questionable from a rule of law perspective whether a law should seek to identify the specific companies it will apply to in advance.

Lessons can be drawn from the UK’s DMCC, which has made a similar mistake. Pursuant to the current proposal for a DMCC, the UK’s CMA will be able to designate a company as having “significant market status” (“SMS”) where it takes part in a ‘digital activity linked to the United Kingdom’, and, in relation to this digital activity, has ‘substantial and entrenched market power’ and is in ‘a position of strategic significance’ (s. 2), and has a turnover of at least £1 billion in the UK or £25 billion globally (s. 7).[51] The British government has previously stated that the ‘regime will be targeted at a small number of firms’.

However, except for the monetary threshold, the SMS criteria are all broadly defined, and could in theory capture as many as 530 companies (as of March 2022, there were 530 companies with more than £1 billion in revenue in the United Kingdom, according to the Office for National Statistics).[52] Thus, although the government claims that the new regime is aimed at a handful of companies, in practice the CMA will have the power to interfere in a variety of new ways across wide swaths of the economy.

Article 9 of Bill 2768 runs into a similar problem. Granted, it identifies the types of services to which the Bill would apply in a way that the DMCC does not. However, some of the categories envisaged are still very broad: for example, online intermediation services could cover any website that connects buyers and sellers or facilitates transactions between two parties. “Operating systems” are prevalent electronic devices well beyond Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android. Indeed, an operating system is just a program or set of programs of a computer system, which manages the physical resources (hardware), the execution protocols of the rest of the content (software), as well as the user interface. They can be found in many everyday devices, either through graphical user interfaces, desktop environments, window managers or command lines, depending on the nature of the device.

Companies delivering these services, no matter their competitive position, market share, the industry they are a part of, or any other economic or factual considerations, would all be caught by Bill 2768, as long as they fulfilled the (low) R$70 million threshold. The upshot is that the enforcer will be able to apply Bill 2768 against a host of wildly different companies, some of which might not really be in a position to harm competition or misuse their market power. As a consequence, the Bill risks discouraging growth, innovation and, indeed, success, as companies become wary of growing past a certain threshold for fear of being caught in the regulator’s crosshairs. Coupled with a reversal of the burden of proof and the possibility of ignoring efficiencies arguments, the Bill would give the enforcer massive, unchecked powers, which could raise rule of law issues.

This problem can be remedied, at least to some extent, by adding a series of qualitative criteria that may or may not work cumulatively with the quantitative thresholds laid down in the Bill. These criteria should require a showing that the companies in question control access to essential facilities, that such facilities cannot be reasonably replicated, and that access is being denied with the threat that competition on the market may be eliminated (refer to Question 1 for discussion on integrating the essential facilities doctrine into Bill 2768). In addition, Bill 2768 should leverage existing measurements of market power from competition law, such as the ability to control output and increase prices. Quantitative criteria, if used, should be significantly higher and also refer to the number of active users on each platform service covered. “Active user” should in this sense be defined as a user who uses a specific service at least once daily and, at a minimum, once weekly.

Question 12

What did you think of the rules on the Digital Platforms Supervisory Fund in art. 15 of Bill 2768/2022? Is there another way to finance this type of government regulatory activity?

There are many ways of financing governmental regulatory activity that do not require the targeted companies to pay an annual tax. Government agencies are typically financed from the general government budget — and it should be the same for the agency enforcing Bill 2768.

There are at least two issues with the current approach under Art. 15. The first is capture. If an agency’s activity is funded by the regulated companies, this can lead to the capture of the agency by the regulated company and facilitate rent-seeking — i.e., the situation in which a company uses the regulator to gain an unfair advantage over rivals. Second, it also creates an incentive on the part of the agency, and the government, to widen the scope of the targeted companies, as a way to secure more funding and resources. This creates a perverse incentive that does not align with the public interest. It also discourages investment and, in a sense, is tantamount to a racket by the government.

Moreover, to the extent that the Bill operates as a direct and targeted constraint on certain companies’ exercise of their economic liberty and private property rights for the presumed benefit of the public welfare, it seems appropriate that it should be funded by general-revenue funds, apportioned according to current tax policy over the entire tax-paying population.

Question 13

To what extent do you believe that all the problems addressed in Bill 2768/2022 are already adequately addressed by competition law, more specifically by CADE, with the instruments of Law No. 12,529 of 2011?

Please see the response to Question 10.

The fact that the government is asking this question at this stage in the process suggests that perhaps the scope and the particulars of Bill 2768 have not been thoroughly thought out. Bill 2768 should be passed only if it is clear that Brazilian competition law is not up to the task. By comparison, and as indicated in the answer to Question 10 above, virtually all of the conduct in the EU’s DMA has also been addressed through EU competition law — often in the Commission’s favor. However, the EU wanted to codify a set of rules that would ensure that the Commission did not have to litigate cases before the courts and would win every case — or at least the vast majority of cases — against digital platforms. But this decision, which one may or may not agree with, came after at least some experience applying competition law to digital platforms and a determination that the gains of such an approach would outweigh the manifest costs.

Conversely, Brazil’s CADE enjoys much more limited experience in this sense, and Brazil itself presents very different economic realities and consumer interests that may not yield the same cost/benefit analysis. As mentioned above, the only “penalties” CADE has imposed against “digital platforms” resulted from voluntary settlements, meaning there has been limited need to litigate “digital” cases in Brazil. There is a lingering sense that Bill 2768 has been proposed not in response to deficiencies in the existing competition law framework, or in response to identified needs particular to Brazil, but as a response to “global trends” initiated by the EU.

Art. 13 of Bill 2768, for example, provides that mergers by covered companies will be scrutinized pursuant to the general competition law rules applicable to other companies and in other sectors. It is unclear why the same logic could not apply across the board — i.e., to all potentially anticompetitive conduct by targeted companies. Why does some conduct which can be addressed through antitrust law necessitate special regulation, but not others?

Question 14

What problems could be generated for the innovation activity of digital platforms if there is the regulation of digital platforms proposed by Bill 2768/2022? Could this be dealt with in any way within Bill 2768/2022?

Indeed, it is by no means clear that Brazil’s particular circumstances are amenable to an “ex ante” approach similar to that of the EU.

Broad prohibitions and obligations such as the ones imposed by Art. 10 of Bill 2768 risk chilling innovative conduct and freezing technology in place. As the tenth ranked country in the global information technology market and with hundreds of startups in the AI sector, Brazil is a burgeoning market with tremendous potential.[53] Its 214 million population means that growth trends are poised to continue — and, sure enough, the number of app jobs grew by 54% in 2023 compared to 2019.[54]

However, static, strict rules such as those envisioned by Bill 2768 can nip the growth of Brazilian startups in the bud by imposing unsurmountable regulatory costs (which would, in any case, benefit incumbents compared to smaller competitors) and banning conduct capable of fostering growth, benefiting consumers, and igniting competition, such as self-preferencing and refusal to deal.

Indeed, both practices can — and often are — socially beneficial. As discussed in Question 8, despite its recent malignment by some policymakers, “self-preferencing” is normal business conduct and a key reason for efficient vertical integration, which avoids double marginalization and allows companies to better coordinate production, distribution, and sale more efficiently — all to the ultimate benefits of consumers. For example, retail services such as Amazon self-preferencing their own delivery services, as in the case of “Fulfilled by Amazon,” gives consumers something they value tremendously: a guarantee of quick delivery. As we have written elsewhere:

Amazon’s granting marketplace privileges to [Fulfilled by Amazon] products may help users to select the products that Amazon can guarantee will best satisfy their needs. This is perfectly plausible, as customers have repeatedly shown that they often prefer less open, less neutral options.[55]

In a recent report, the Australian Competition Commission recognized as much, stating that self-preferencing is often benign and can lead to procompetitive benefits.[56] Indeed, there are many legitimate reasons why companies may choose to self-preference, including better customer experience, customer service, more relevant choice (curation), and lower prices.[57] Thus, banning self-preferencing, or otherwise significantly discouraging companies from engaging in self-preferencing, could hamstring company growth — including by Brazilian companies that are currently in an early stage of development — and impede market entry by companies who could have been innovators.

Similarly, forcing companies to deal with third parties could stifle innovation by incentivizing free-riding and discouraging companies from making investments. Indeed, why would a company innovate or invest if it knows it will then have to share such investments and innovations with passive rivals who have undertaken none of these risks? The consequence is a stalemate where, rather than fighting to be the first to innovate and enjoy the fruits borne of such innovation, companies are rather encouraged to game the system by waiting for others to make the first step and then free riding on their achievements. This essentially upends the process of dynamic competition by artificially rearranging the incentive to innovate and invest vs. the incentive to free ride, reducing the benefits of the former and increasing the benefits of the latter.

It would be catastrophic to drive a wedge in Brazil’s ability to grow its technology sector and innovate — especially considering the country’s vast potential. Indeed, rather than a triumph of regulation over innovation, Brazil should strive to be precisely the opposite.[58]

Question 15

What would be the practical difficulties of applying this type of legislation contemplated by Bill 2768/2022?

Funds to finance what could be a considerable amount of enforcement are necessary, but not sufficient, to ensure effectiveness. In the EU, the Commission’s DG Competition, one of the world’s foremost and best-endowed competition authorities, has famously struggled to hire the staff necessary to implement the Digital Markets Act. In short, “DMA experts” currently do not exist — and the Commission will either have to train such experts itself or hire them when expertise develops through enforcement. But this creates a chicken-and-egg scenario, where enforcement — or at least good enforcement — cannot happen without good experts, and good experts cannot materialize without enforcement. There is no reason to believe that these considerations do not map onto the Brazilian context.

Brazil faces an additional challenge, however: attracting talent. Unlike in the EU, where posts at the Commission are highly coveted due to the high salaries, perks, and job security they confer, CADE’s resources are more modest and likely cannot compete fully with the private sector. Thus, before passing Bill 2768, the government should be clear on how the law would be enforced, and by whom.

Other issues include the heavy compliance burden of the Bill, which will affect not only the so-called “tech giants” but any company above the modest R$70 million turnover threshold, the difficulties in interpreting the ambiguous prohibitions and obligations contemplated in Art. 10 (and the litigation which may ensue, on which see Question 16), the cost of crafting of adequate remedies within the meaning of Art. 10, and the looming possibility that the Bill will capture procompetitive conduct and stifle innovation. As we have written with respect to ASEAN countries and the possibility of implementing EU-style competition regulation there:

The ASEAN nations exhibit extremely diverse policies regarding the role of government in the economy. Put simply, some of the ASEAN nations seem ill-suited to the far-reaching technocracy that almost inevitably flows from adopting the European model of competition enforcement. Others might simply not have sufficient resources to staff agencies that could, satisfactorily, undertake the type of far-reaching investigations that the European Commission is famous for.[59]

Question 16

Do you see a lot of room for the judicialization of this type of regulation provided for in Bill 2768/2022? On what devices?

The enforcement of Bill 2768 is likely to lead to substantial litigation, not least because many of the core concepts of the Bill are ambiguous and open to interpretation.

For instance, what does “discriminatory” conduct within the meaning of Art. 10, para. II entail? Can a covered platform treat business users differently based on objective criteria, such as quality, history, and trustworthiness, or must all business users be treated equally? In this sense, it is uncertain whether the specific meaning ascribed to “discriminatory conduct” under competition law applies in this context. Similarly, what does “adequate” use of data collected in the exercise of a firm’s activities mean (paragraph III)? Does paragraph IV of Art. 10 imply that a covered platform can never deny access to business users? Presumably, covered platforms will want to know how and why this general obligation deviates from the narrower essential facilities doctrine under Brazilian competition law.

Art. 11 adds certain caveats to this, such as that intervention should be tailored, proportionate and consider the impact, costs, and benefits. Again, what sort of impact, costs and benefits are relevant — on consumers, business users, the covered platform, society as a whole?

If this is anything to go by, Bill 2768 is likely to be a legally contentious one.

Question 17

Are the definitions in article 6 of Bill 2768/2022 adequate for the purpose of this proposal?

Art. 6 and, indeed, the entire impetus behind Bill 2768, rests on two questionable assumptions:

- That covered products and services are different from other products or services; and

- That these products and services are sufficiently similar to be considered (and regulated) as a group.

The former would be more convincing if the remedies contemplated by the Bill, such as non-discrimination, adequate use of data, and access, had not been previously used in other markets and for other products. Granting access on “Fair, Reasonable, and Nondiscriminatory” (“FRAND”) terms is often used in the context of competition law and IP law, both of which apply across industries. The duty to use data “adequately” is generally contemplated by data protection laws, which also apply broadly. The same can be said for access obligations, which are frequent under competition law and in regulated industries (such as telecommunications or railways).

In addition, neither the products and services in Art. 6 of the Bill, the companies that operate them, nor the business models they employ are monolithic. Voice assistants and social media, for instance, are vastly different products. The same can be said about cloud computing, which is not really a “platform” in the sense that, say, online intermediation is. The products and services in Art. 6 themselves are also highly heterogeneous, with a single category encompassing a motley list of products, from e-commerce to online maps and app stores.

The same argument applies to the companies that sell these products and services, which — despite the ubiquitous “Big Tech” moniker — are ultimately very different firms.[60] As Apple CEO Tim Cook has said: “Tech is not monolithic. That would be like saying ‘All restaurants are the same’ or ‘All TV networks are the same.’”[61]

For instance, while Google (Alphabet) and Facebook (Meta) are information-technology firms that specialize in online advertising, Apple remains primarily an electronics company, with around 75% of its revenue coming from the sale of iMacs, iPhones, iPads, and accessories. As Amanda Lotz of the University of Michigan has observed:

The profits on those [hardware] sales let Apple use very different strategies than the non-hardware [“Big Tech”] companies with which it is often compared.[62]

It also means that most of its other businesses — such as iMessage, iTunes, Apple Pay, etc. — are complements that “Apple uses strategically to support its primary focus as a hardware company.” Amazon, on the other hand, is primarily a retailer, with its Amazon Web Services and advertising divisions accounting for just 15% and 7% of the company’s revenue, respectively.[63]

Even when two “gatekeepers” are active in the same products/service market, they often have markedly different business models and practices. Thus, despite both selling mobile-phone operating systems, Android (Google) and Apple employ very different product-design philosophies. As we argued in an amicus curiae brief submitted last month to the U.S. Supreme Court in Apple v. Epic Games:

For Apple and its users, the touchstone of a good platform is not “openness,” but carefully curated selection and security, understood broadly as encompassing the removal of objectionable content, protection of privacy, and protection from “social engineering,” and the like.… By contrast, Android’s bet is on the open platform model, which sacrifices some degree of security for the greater variety and customization associated with more open distribution. These are legitimate differences in product design and business philosophy.[64]

These various companies and markets have diverse incentives, strategies, and product designs, therefore belying the idea that there is any economically and technically coherent notion of what comprises “gatekeeping.” In other words, both the products and services that would be subject to Art. 6 of Bill 2768 and those companies themselves are highly heterogeneous, and it is unclear why they are placed under the same umbrella.

Question 18

Instead of pure ex-ante regulation, would any other type of monitoring and/or regulation of digital markets make sense?