Doomsday Mergers: A Retrospective Study of False Alarms

Executive Summary

A well-placed cadre of progressive scholars and advocates—several of whom have in more recent years come to occupy top positions in America’s antitrust agencies—have long-focused their attention distinctly on high-profile mergers and acquisitions. For more than a decade, hardly a deal could be proposed without these critics claiming that it would create an unassailable monopoly, be the final nail in the coffin of small businesses, and/or cement the political sway of big business. For these so-called “neo-Brandeisian” critics, the repeated pattern has been, first, to entreat authorities to block these deals and then, should they be cleared nonetheless, to cite such approvals as evidence that U.S. antitrust law is in dire need of reform.

The bombastic rhetoric employed by these critics stands in sharp contrast with the technocratic and measured approach to enforcement that has traditionally been the norm for U.S. antitrust agencies and courts. Indeed, for better or worse, antitrust case law in the United States generally focuses on tangible and short-term metrics, rather than hypothetical doomsday scenarios that are notoriously hard to predict. Under this measured approach—rooted in the consumer welfare standard—theories of harm are dismissed if they rely on mere conjecture. Unsurprisingly, the critics have routinely lambasted this status quo.

But the paradigm has been shifting. With the elevation of progressive critics such as Lina Khan to chair the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Jonathan Kanter to head the U.S. Justice Department’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division, and Tim Wu to serve as special assistant to President Joe Biden for technology and competition policy, the tide of U.S. antitrust enforcement may be turning. In recent months, the antitrust agencies have brought several high-profile suits that seek to combat what their new leadership believes to be excessive corporate consolidation. This includes the FTC’s failed challenge of the Meta-Within deal, as well as ongoing cases against the Microsoft-Activision Blizzard and Illumina-Grail mergers.

The rhetoric accompanying these challenges has departed significantly from traditional antitrust discourse and has instead been more closely aligned with the populist style that these agencies’ leaders employed before their nominations. For instance, in its Meta-Within complaint, the FTC argued that clearing the deal would put Meta “one step closer to its ultimate goal of owning the entire ‘Metaverse.’” In the Illumina-Grail suits, the agency claimed that “after the Acquisition, Illumina will control the fate of every potential rival to Grail for the foreseeable future.”

Against this backdrop of increasingly alarmist merger claims, this paper analyzes whether previous doomsday merger scenarios have materialized, or whether the critics’ claims missed the mark. Our retrospective analysis shows that many of the alarmist predictions of the past were completely untethered from prevailing market realities, as well as far removed from the outcomes that emerged after the mergers.

Amazon-Whole Foods

The first merger we look at is Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods. Critics at the time claimed the deal would reinforce Amazon’s dominance of online retail and enable it to crush competitors in physical retail. As now-FTC Chair Lina Khan put it: “Buying Whole Foods will enable Amazon to leverage and amplify the extraordinary power it enjoys in online markets and delivery, making an even greater share of commerce part of its fief.”

These claims turned out to be a bust. As we explain, at the time of writing, several large retailers have grown faster than Amazon; Whole Foods’ market share has barely budged; and several new players have entered the online retail space. Moreover, the Amazon-Whole Foods deal appears to have delivered lower grocery prices and increased convenience to consumers.

Beer-Industry Consolidation

A second notable example comes from the beer industry. In the early 2000s, the industry witnessed a wave of consolidation, culminating with ABI’s acquisition of SABMiller in 2016, which critics claimed would increase the price of beer and decimate the burgeoning craft-beer segment.

Instead, the concentration of the beer industry decreased after the mergers, prices did not increase on average, and the craft-beer segment thrived. This is not to say that all is rosy; the price of some beers did indeed increase after the wave of mergers. Regardless, it is clear the post-merger outcome was a far cry from the doomsday scenario that critics predicted.

Bayer-Monsanto

Along similar lines, Bayer’s acquisition of Monsanto (along with the Dow-Dupont merger) was met with stern rebukes from policymakers and academics. Critics argued that the merger would raise the price of key seeds, such as corn, soy, and cotton. Perhaps more fundamentally, the deal’s opponents argued it would further concentrate the agri-food industry, forcing farmers to deal with only a handful of seed providers. Accordingly, many cited this merger as evidence that antitrust merger enforcement needed reform.

Fast forward to today, and these fears appear overblown. Seed prices have remained roughly constant (though we do not know the counterfactual), and there is little evidence that the life of farmers and rural communities has been significantly affected by the merger. There is thus little reason to believe that the mergers justified the legislative and policy changes that many called for at the time.

Google-Fitbit

Google’s acquisition of Fitbit is another case where progressive scholars’ dire predictions failed to materialize. The deal’s opponents claimed the merger would reinforce Google’s position in the ad industry and prevent new entry; harm user privacy by enabling Google to integrate Fitbit health data into its other ad services (or sell this data to health insurers); and crush burgeoning rivals in the wearable-device industry.

At the time of writing, available evidence suggests the exact opposite has occurred: Google’s share of the online-advertising industry has declined, as has Fitbit’s position in the wearable-devices segment. Likewise, Google does not use data from Fitbit in its advertising platform; not even in the United States, where it remains free to do so. Meanwhile, the merger enabled Google’s entry into the smartwatch market as an upstart competitor against the market leader, Apple. In short, enforcers’ “terrible decision” to clear the merger appears vindicated.

Facebook-Instagram

Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram provides a different perspective. At the time, basically no one worried about it from an antitrust perspective and many pundits lambasted the purchase as a poor business decision. It is only in retrospect that people have started to see it as the merger that got away and evidence of the problems with allegedly weak enforcement. This perspective ignores the fact that enforcement agencies only ever have that data which is available at the time.

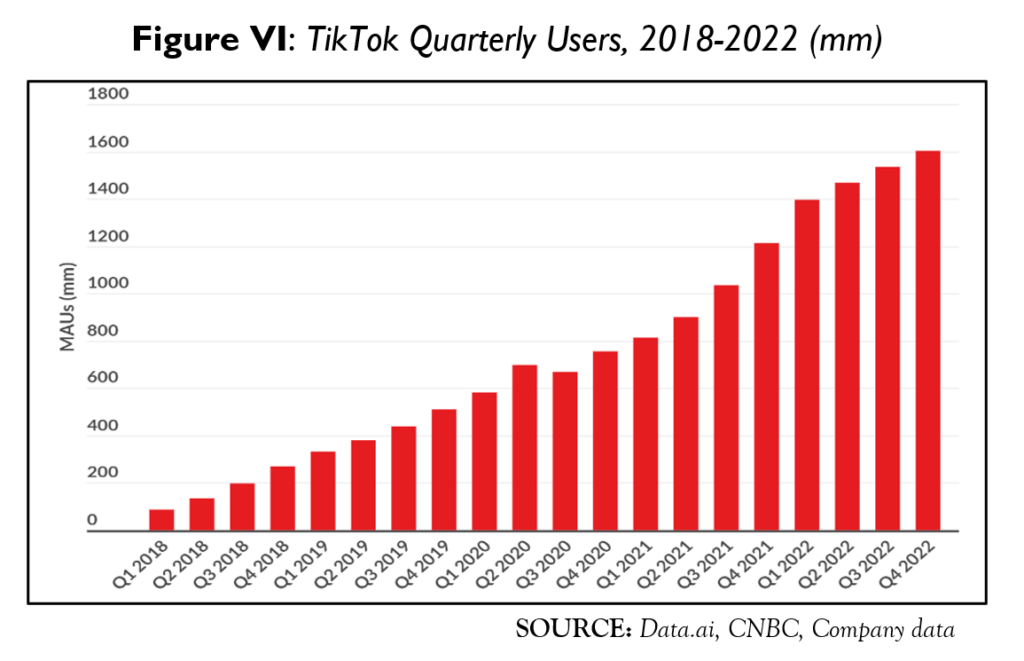

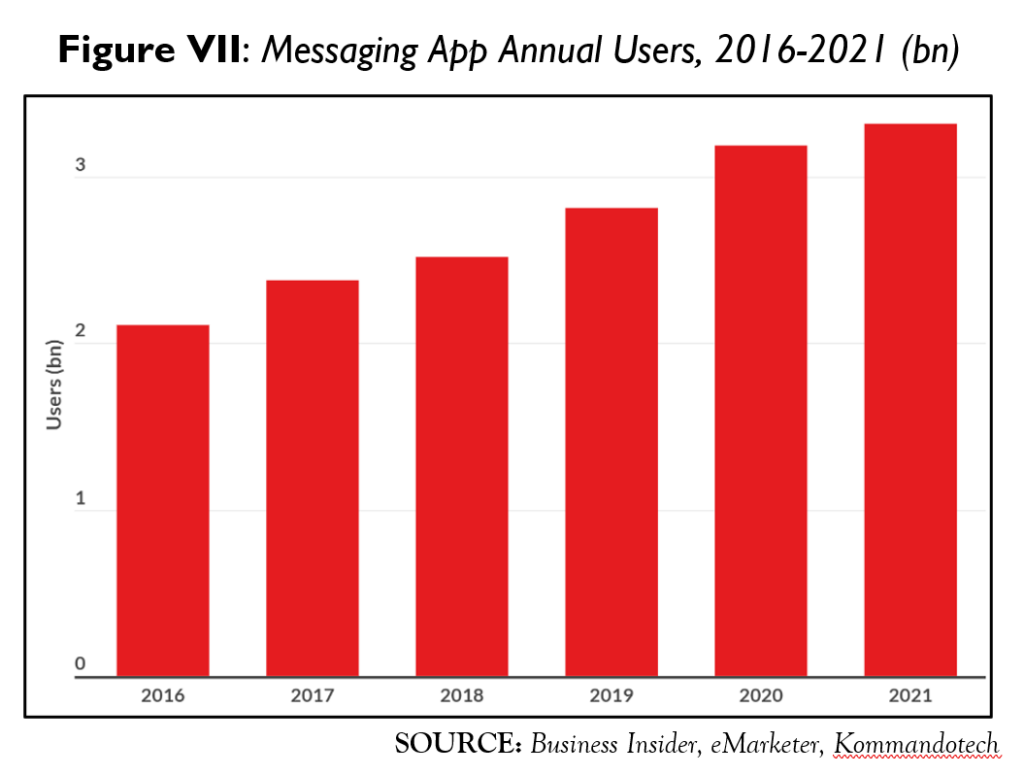

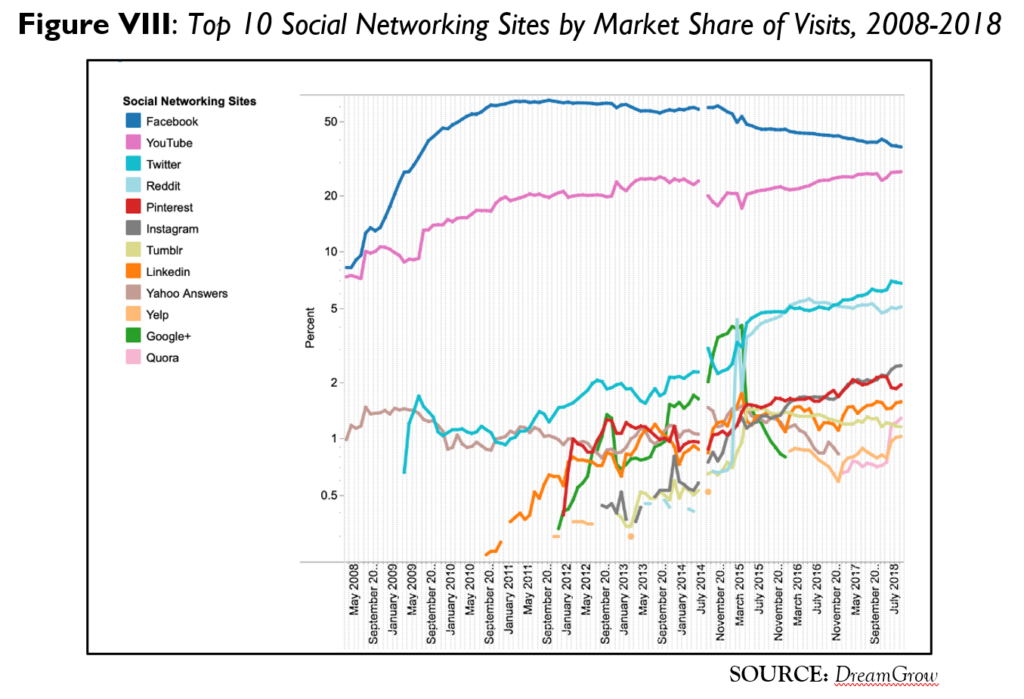

Even in retrospect, however, it is far from obvious that the acquisition was anticompetitive. Immediately upon purchase, Facebook was able to bring Instagram’s photo-editing features to a much larger audience, generating value for users. Only later did Instagram turn into the social-media giant that we know today. The recent rise of TikTok casts further doubt on claims regarding the supposed market dominance of a combined Facebook and Instagram. A merger that benefited consumers without generating impenetrable market dominance hardly seems like overwhelming proof of the failures of enforcement.

Ticketmaster-Live Nation

We close with Ticketmaster for two reasons. First, it has received significant negative attention recently due to technical failures during Taylor Swift’s latest concert sales, which has prompted the DOJ to investigate the company. Second, people have complained about Ticketmaster being a monopolist ever since it came to prominence. Yet, there was little outrage at the merger with Live Nation. While there was a congressional hearing at the time and some concern expressed in The New York Times, the contemporaneous claims were refreshingly mild relative to more recent comments by the neo-Brandeisians.

Despite having antitrust authorities investigate its previous acquisitions, including the merger with Live Nation, Ticketmaster has avoided having any of its mergers blocked outright. Perhaps more importantly, Ticketmaster’s market share appears to have fallen following the merger with Live Nation. There is thus little sense that the deal harmed consumers. So why the disconnect between longstanding frustration and antitrust enforcement? The agencies have seen the beneficial effects of mergers in a difficult multi-sided market between fans, venues, and artists. After investigation, the agencies found that the merger was primarily a vertical one between a ticketing website (Ticketmaster) and a concert promoter (Live Nation), which could be pro-competitive for the overall multi-sided market. The DOJ placed behavioral remedies in place and allowed the merger. We explain how a technical failure more than a decade later can hardly be blamed on the antitrust authorities for letting it slip through.

The Upshot

One potential counterargument to the focus of this paper is that the mergers we discuss may not be representative of broader trends—and, accordingly, that tougher antitrust enforcement may still be warranted. While this is a possibility, it misses our main point. Too often, mergers are met with alarmist fearmongering in policy circles, with many observers arguing a given transaction will irrevocably harm consumers and the economy. These calls for action occur despite the existence of a highly sophisticated merger-control apparatus that is designed precisely to minimize the likelihood of such harms, while enabling consumer-benefitting transactions to pass regulatory muster.

Our call for regulatory prudence may seem modest, but it increasingly faces challenges. The most high-profile challenge is perhaps the FTC and DOJ’s joint repudiation of the most recent (2010) merger guidelines, and their ongoing effort to revise the guidelines, almost certainly in ways to facilitate more aggressive merger enforcement. As FTC Chair Lina Khan remarked upon the initiation of the merger-guidelines-revision effort, in the wake of merger activity allegedly due to lax enforcement, “many Americans historically have lost out, with diminished opportunity, higher prices, lower wages, and lagging innovation…. These facts invite us to assess how our merger policy tools can better equip us to… halt this trend.”

And as Matt Stoller approvingly notes of the revision effort, “mergers are the key fulcrum that has consolidated power in American society. And now, for the first time in our lifetimes, antitrust enforcers are genuinely pushing back, with real merger challenges and now a revamp of this until-now catastrophic set of guidelines.”

Many in the media have similarly pushed for more aggressive merger enforcement, unmoored from its economic rigor. A recent Financial Times piece by Rana Foroohar, for example, encapsulates the prevailing zeitgeist, intimating as it does that authorities should ditch sophisticated and technocratic economics in favor of what she calls “kitchen table economics,” in which “economic policy discussions [should be in] the purview of not just economists, but also lawyers, activists and ordinary people.”

If there is one thing to take away from our paper, it is that basing merger enforcement on kitchen-table economics—the idiosyncratic preferences of “activists and ordinary people”—would be disastrous. Our retrospective study shows that popular and populist fears about corporate consolidation are often completely untethered from economic reality and wildly erroneous. The less these fears influence antitrust policy, the better.

Introduction

Antitrust law and policy may be on the move. The neo-Brandeisian antitrust movement advocates radical reform,[1] and seems not so much ascendent as ascended, finding support in the White House[2] and at the head of the two federal antitrust agencies, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)[3] and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ).[4]

In remarks often quoted or echoed by FTC Chair Lina Khan, President Joe Biden laments that “we’ve lost the fundamental American idea that true capitalism depends on fair and open competition.”[5] He lays that supposed loss at the feet of antitrust: “Forty years ago, we chose the wrong path, in my view, following the misguided philosophy of people like Robert Bork, and pulled back on enforcing laws to promote competition.”[6]

The bombastic rhetoric employed by these critics stands in sharp contrast with the technocratic and measured approach to enforcement that has traditionally been the norm for U.S. antitrust agencies and courts. Indeed, for better or worse, antitrust case law in the United States generally focuses on tangible and short-term metrics, rather than hypothetical doomsday scenarios that are notoriously hard to predict. Under this measured approach—rooted in the consumer welfare standard—theories of harm are dismissed if they rely on mere conjecture.[7] Unsurprisingly, the critics have routinely lambasted this status quo.[8]

These neo-Brandeisian ideas are now starting to filter into mainstream antitrust policy. With the elevation of progressive critics such as Lina Khan to chair the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Jonathan Kanter to head the U.S. Justice Department’s (DOJ) Antitrust Division, and Tim Wu to serve as special assistant to President Joe Biden for technology and competition policy, the tide of U.S. antitrust enforcement may be turning. In recent months, the antitrust agencies have brought several high-profile suits that seek to combat what their new leadership believes to be excessive corporate consolidation. This includes the FTC’s failed challenge of the Meta-Within deal, as well as ongoing cases against the Microsoft-Activision Blizzard and Illumina-Grail mergers.[9]

The rhetoric accompanying these challenges has departed significantly from traditional antitrust discourse and has instead been more closely aligned with the populist style that these agencies’ leaders employed before their nominations. For instance, in its Meta-Within complaint, the FTC argued that clearing the deal would put Meta “one step closer to its ultimate goal of owning the entire ‘Metaverse.’”[10] In the Illumina-Grail suits, the agency claimed that “after the Acquisition, Illumina will control the fate of every potential rival to Grail for the foreseeable future.”[11]

Meanwhile, the FTC recently issued a new Statement of Enforcement Principles Regarding “Unfair Methods of Competition” Under Section 5 of the FTC Act[12] that turns the established methods, measures, and goals of antitrust on their heads.[13] It rejects, among other things, the consumer welfare standard and the rule of reason that are at the heart of contemporary antitrust jurisprudence. And more importantly for this paper, it is anticipated that the FTC and the Antitrust Division will soon release new merger guidelines, covering both horizontal and vertical mergers. The agencies have launched a “Request for Information on Merger Enforcement,”[14] soliciting public input on diverse issues that range from basic concepts, evidence, and analytical methods to the goals of merger enforcement, some 91 questions under 15 topical headings. More recent statements from the agencies suggest that new guidelines are forthcoming.[15]

The agencies’ aim seems clear: strengthening—or at least increasing—antitrust merger enforcement.[16] Khan has quoted from President Biden’s executive order that “industry consolidation and weakened competition have ‘den[ied] Americans the benefits of an open economy,’ with ‘workers, farmers, small businesses, and consumers paying the price.”[17] That same executive order includes a general condemnation of the state of U.S. competition, which it blames on “Federal Government inaction”—that is, on a putative failure of antitrust enforcement. Khan goes on to note that:

[The merger guidelines review] comes against the backdrop of a broader reassessment of the effects of mergers across the U.S. economy. Evidence suggests that decades of mergers have been a key driver of consolidation across industries, with this latest merger wave threatening to concentrate our markets further yet…. While the current merger boom has delivered massive fees for investment banks, evidence suggests that many Americans historically have lost out, with diminished opportunity, higher prices, lower wages, and lagging innovation. A lack of competition also appears to have left segments of our economy more brittle, as consolidated supply and reduced investment in capacity can render us less resilient in the face of shocks.

These facts invite us to assess how our merger policy tools can better equip us to discharge our statutory obligations and halt this trend.[18]

And as Matt Stoller approvingly notes of the revision effort, “mergers are the key fulcrum that has consolidated power in American society. And now, for the first time in our lifetimes, antitrust enforcers are genuinely pushing back, with real merger challenges and now a revamp of this until-now catastrophic set of guidelines.”[19] Whether or to what extent this drive for revision or reform might find support in the federal courts is less clear.[20]

Neo-Brandeisian scholars are not the only ones pushing for substantial reform and, specifically, considerably increased interventions by antitrust enforcers into mergers and other commercial conduct. For example, the American Antitrust Institute (AAI) identifies itself as an original and central player in “the modern ‘progressive antitrust’ movement.”[21] The AAI advocates for “vigorous” public enforcement, characterizing its mission as a reaction against “the conservative law and economics movement,”[22] which, AAI says, “steered antitrust policy in a non-interventionist direction marked by lax merger control and forbearance from policing monopolistic and other anticompetitive practices.”[23] While AAI has a decidedly pro-intervention perspective, it is arguably more moderate and research-based than the neo-Brandeisian movement. Yet, collectively, progressive antitrust advocates and neo-Brandeisians have formed a vocal movement in favor of more invasive antitrust enforcement, based on a shared view that lax enforcement has caused unremedied harm throughout the economy.

And many in the media have similarly pushed for more aggressive merger enforcement, unmoored from its economic rigor. A recent Financial Times piece by Rana Foroohar, for example, intimated that authorities should ditch sophisticated and technocratic economics in favor of what she calls “kitchen table economics.” Her piece encapsulates the prevailing zeitgeist:

The popularisation of antitrust is part of a much larger shift in which economic policy discussions are increasingly the purview of not just economists, but also lawyers, activists and ordinary people. These groups are less interested in technocratic debates about market mechanisms than in a grassroots discussion about how corporate power has distorted the market in ways that they find absurd….

Thus, traditional economic theories about markets are no more, or less, useful than the collection of real world facts that either side can bring to a case.”[24]

The classic problem with most antitrust enforcement—and merger enforcement, in particular—is that it is prospective; it entails making predictions about future effects and determining appropriate enforcement under conditions of uncertainty. Proponents of more vigorous enforcement assert that past failures to enforce have led to great economic harms and, thus, that merger policy should be categorically more stringent to protect against such harms in the future. But it is an open question whether these claims are accurate, and an even harder question to answer whether more stringent enforcement in any particular case would be desirable, even if it were established that an overall increase in enforcement would be. It is almost certain that separating merger enforcement policy from economic rigor would magnify this uncertainty.

This paper seeks to assess predictions from progressive and neo-Brandeisian advocates regarding the immense harm that past mergers would supposedly cause. We examine six selected mergers that were widely condemned, but nevertheless consummated, prior to the current administration’s appointment of its competition-policy team.[25] We assess whether the predictions concerning these mergers’ deleterious effects have ultimately materialized. The goal of this paper is not to provide rigorous, empirical analysis of the effects of these seven mergers, but rather to provide an accurate—but necessarily casual—assessment of the state of the post-merger markets. Using public information and relying on the insights of industry experts, we offer a detailed picture of these markets and an assessment of how they may have changed post-merger.

Our analysis shows that critics of the antitrust status quo routinely make dire predictions concerning the likely future effects of mergers that, as we explain, tend to be wide of the mark. This is not surprising: there is a reason why antitrust merger enforcement is entrusted to technocratic antitrust authorities with, among other assets, huge teams of PhD economists to run merger simulations. At the very least, however, our analysis suggests popular claims that given mergers will be harmful should be taken with a grain of salt; such claims tend to say more about the person making them than they do the likely effects of a merger. Likewise, these same scholars also routinely claim that antitrust merger enforcement is insufficient precisely because it enabled these mergers to go through unchallenged. Again, our analysis suggests that things are (unsurprisingly) more complicated: no single merger provides a silver bullet to sustain claims that antitrust merger enforcement is too lax—something that needs to be shown empirically.

While our selection of mergers is ultimately somewhat arbitrary, the list includes some of the most contentious mergers of the past decade. Our selection has been guided by public statements about these mergers by prominent neo-Brandeisians and others. Unifying themes are, first, the contention that antitrust enforcement had fundamentally dropped the ball and, second, that dire consequences would follow.

Two caveats are in order. First, statements from the neo-Brandeisian movement—sometimes called “populist”[26] or “hipster antitrust”[27]— have not been monolithic: this is an identifiable (and self-identified)[28] movement, but it is united by common concerns and an orientation, not by any official positions or definitive membership.[29] Still, there is an identifiable family of statements that has been directionally consistent, and often dire.[30] Second, although we cite to specific individuals, our focus is not on those individuals or the neo-Brandeisian movement per se. Rather, we examine certain dire predictions about specific mergers, and the reasoning that lay behind those predictions. While these are characteristic of certain staunch advocates of substantially greater intervention into mergers, the predictions were not all made by individuals associated with the neo-Brandeisian movement. Moreover, we do not assume that views or assessments, or methodological or theoretical priors, are uniform across a wider group of progressives. Given the considerable political influence of the neo-Brandeisians, however, it is not impertinent to ask whether they are generally correct in their policy prescriptions.

In brief, we examine a string of what might be called doomsday merger predictions. All of these mergers were supposed to damage competition and raise prices. For example, when Amazon acquired Whole Foods, Barry Lynn of Open Markets—an organization commonly associated with the neo-Brandeisians—provided a dire and sweeping assessment to the New Republic: “This is the crushing of competition. Amazon is monopolizing commerce in the United States.” “Commerce” seems an awfully broad market for antitrust analysis, but Lynn offered no further qualification about, e.g., “premium natural and organic food markets,”[31] online retail commerce, or even retail commerce writ large. Rather, the acquisition—a sizeable acquisition of a mid-sized grocery chain that was not among the 20 largest in the United States—would somehow lead to Amazon’s monopolization of commerce. Lynn would go on to say that only Uncle Sam would be able to save competitors from certain death.[32]

In less hyperbolic terms, in 2014, it was predicted that the merger of ABI and SAB Miller would “impose significant price increases on consumers” and “undermine the continued emergence of craft beer.”[33] While there is evidence of slight price increases associated with certain previous mergers, such as the Miller-Coors merger that we analyze in this paper, the growing craft-beer trend has continued apace. In 2020, six years after dire predictions about ABI/SAB Miller, the staffs of the FTC and the Antitrust Division jointly observed a long-running growth trend in comments on a proposed policy change in California: in California alone, there were 200 craft brewers in 2000 and 1,039 in 2020.[34] There, the staffs’ concerns had to do with regulatory barriers to competition, not manufacturer consolidation.[35]

One final prefatory note about this project and about merger retrospectives generally: Merger retrospectives have played an important role in incremental antitrust reform for several decades. For example, a series of retrospective studies of hospital mergers conducted by the staff of the FTC’s Bureau of Economics—sometimes in collaboration with academic economists—have been identified as key drivers in changing the way the federal courts view hospital mergers, where they seemed central to reversing a trend of agency losses in merger-challenge cases. They have, as well, helped to refine the tools available to enforcers and academic economists. In simplest terms, merger retrospectives examine quantifiable changes in competitively important market outcomes, such as price and output and, where demonstrable, quality or quality-adjusted price.[36] More specifically, retrospective analysis investigates “ex post how, if at all, a particular merger affected equilibrium behavior in one or more markets.”[37]

To be clear, these merger retrospectives are most informative when situated within a larger body of theoretical and empirical research. They do not, in themselves, determine the framework within which, or methods with which, mergers are scrutinized. Moreover, we cannot in this paper hope to rival the deep empirical dives of the FTC’s hospital-merger retrospective series, which ranges over some 20 publications scrutinizing diverse methods and models applied by agency staff in specific investigations and the outcomes of consummated mergers.[38] We can, however, examine competitively relevant indicators such as price and output (and price and output trends), as the merger-retrospective literature has done, as well as such signals as market valuations.

While both we and the reform advocates lack access to much of the granular data and privileged information available to enforcers, that is part of our point: informal or off-the-cuff assessments of the likely competitive effects of any given merger are very likely to be inaccurate, if not plainly wrong, as can be crude indicators of concentration, such as 4-digit NAICS codes, when taken to be indicators of market power. That is part of the insight behind the decades-long shift to fact-intensive, rule-of-reason scrutiny in antitrust, and a conspicuous complication for reformers’ advocacy in favor of a return to per se rules and the development of ex ante antitrust regulations.

I. Amazon-Whole Foods

On June 16, 2017, Amazon revealed its intention to purchase the Whole Foods Market, known commonly as “Whole Foods,” a popular chain of organic and natural grocery stores. Despite Whole Foods’ small 1.2% share of U.S. food and grocery sales,[39] the announcement—along with the FTC’s rapid clearance of the deal—caused an uproar among progressive and interventionist commentators.[40] The merger was completed in August 2017, and Amazon quickly began implementing changes to the Whole Foods business model.

A. The Predictions

Barry Lynn, director of the Open Markets Institute, claimed the deal would crush competition and allow Amazon to monopolize commerce in the United States, adding that only the government could save Amazon’s rivals from certain downfall.[41] Lina Khan—now chair of the FTC—intimated that Amazon would use its data to transfer its dominance from online to physical retail: “Buying Whole Foods will enable Amazon to leverage and amplify the extraordinary power it enjoys in online markets and delivery, making an even greater share of commerce part of its fief.”[42] And, in a now-deleted tweet, Tim Wu called the merger a super-monopoly, referring to the multiple monopolies that Amazon would hold after the merger (presumably adding a grocery monopoly to its dominance of online retail).[43] Writing in The New York Times, Khan further predicted that “this deal would allow Amazon to potentially thwart future innovations.”[44] Other critics, such as Marshall Steinbaum, acknowledged the merger was legal at the time, but that its legality simply showed the flaws in the antitrust doctrine. According to Steinbaum, “this merger is a no-brainer to approve under existing antitrust doctrines, which is exactly why those doctrines are flawed. We, but not the law, know that Amazon is anticompetitive.”[45] The list goes on.

To support their claims, many of these critics pointed to the merger’s short-term effect on the stock market—Amazon’s competitors took a heavy hit when the deal was announced. Because of the share-price losses suffered by the stocks of rival companies, Scott Galloway surmised that markets were failing, and that Amazon should be broken up.[46] Galloway added:

Within twenty-four hours of the Amazon–Whole Foods acquisition announcement, large national grocery stocks fell 5 to 9 percent.

When the subject of monopolistic behavior comes up, Amazon’s public-relations team is quick to cite its favorite number: 4 percent—the share of U. S. retail (online and offline) Amazon controls, only half of Walmart’s market share. It’s a powerful defense against the call to break up the behemoth. But there are other numbers. Numbers you typically won’t see in an Amazon press release: • 34 percent: Amazon’s share of the worldwide cloud business • 44 percent: Amazon’s share of U. S. online commerce.[47]

To summarize, critics claimed that Amazon’s market shares (for both its online-retail platform and physical-retail business) and its stock price would grow faster than rivals’ and lead to increased concentration in these markets and the exit of smaller rivals. This raises a simple question: have these prophecies come to pass?

B. What Happened?

Five years after the merger was consummated, it has become increasingly evident that critics’ claims were wide of the mark. If anything, competition appears to have intensified in both the online and physical spaces, with new firms entering the market and Amazon’s share both markets appearing to decline or at least stagnate.

One important indicator is the stock prices of both Amazon and its rivals. Indeed, if critics were correct and Amazon did indeed grab significant sales from rivals, thus increasing its profits, then its stock price should have outperformed those of rivals. Given the idiosyncratic years we have been through—with the COVID-19 pandemic, a marked increase in inflation, and fears of a widespread recession creating the potential for large outliers—it is worth looking at those share prices both one and five years after the merger.

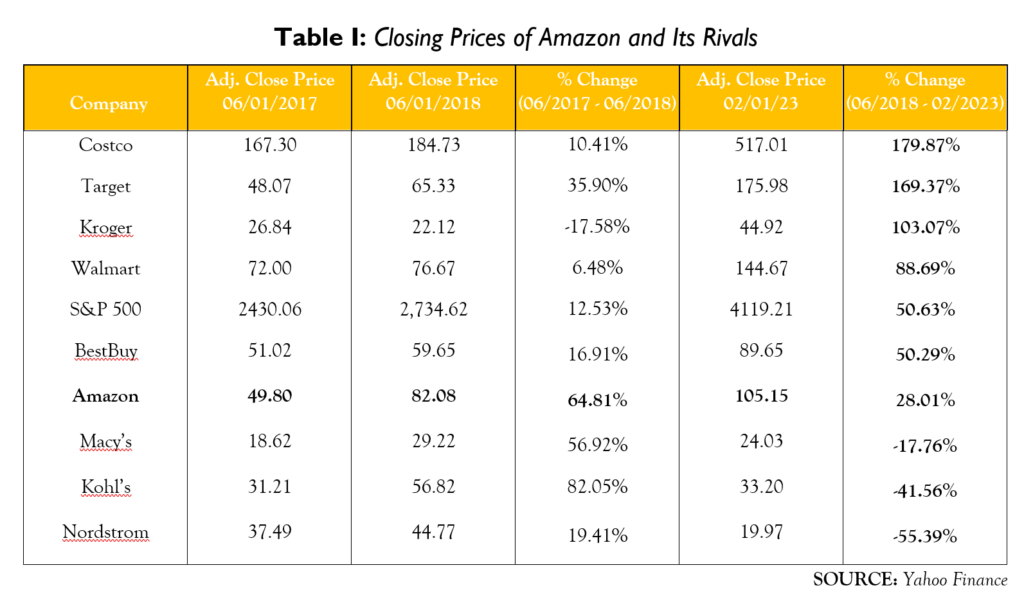

One year after the merger, the picture looked nowhere near as bad as critics’ most dire predictions. The stocks of Amazon’s main rivals registered significant gains in the year following the announcement of the Whole Foods deal. Kohl’s stock actually outperformed Amazon’s (+82.05% versus +64.81%) in the year following the merger. Target, Macy’s, Costco, BestBuy, Kohl’s, and Nordstrom’s also showed healthy gains, rising faster than the S&P 500 index. Of course, firms like J.C. Penney and Sears hit new lows, leading both companies to the edge of bankruptcy (although their decline started well before the Whole Foods merger). In short, the retail industry was still highly competitive, and rivals did not appear to be diminished one year after the merger.

From then on, the market appears to have become even more competitive. Looking at the situation almost five years after the merger, the stocks of many rival companies have significantly outperformed Amazon. These include Costco, Target, Kroger, Walmart, and BestBuy. Granted, this may have something to do with recent decline of tech stocks—a trend that could conceivably be reversed in the future. Whether this recent decline proves permanent or not, the bigger picture is that critics were mistaken when they claimed the merger would cause the food-retail industry to fall under Amazon’s control—notably because of its technological superiority.

Looking at (estimated) market shares tends to paint a similar picture. For a start, available evidence suggests the market share of Whole Foods has not meaningfully increased since its acquisition by Amazon—moving from 1.3% of the U.S. food-retail market to 1.6%.[48] This severely undermines critics’ claims that Amazon would transfer its purported dominance of online retail to physical retail.

The picture is more complicated when looking at Amazon’s online-retail platform. Since the merger, Amazon’s share of online retail has steadily increased from roughly 40% in 2017 to an estimated 56% in 2021 (though this is merely the continuation of a trend that predates the acquisition of Whole Foods).[49] This moderate market-share increase might, at first sight, appear more consistent with critics’ predictions, but a closer look paints a different picture. While Amazon’s share of online retail as a whole has increased relative to many of its rivals, this is not the case for its share of online grocery sales (the part of its online business that should presumably have benefited most from the Whole Foods acquisition). For instance, between 2017 and 2019, Amazon Fresh’s consumer base stagnated, while Walmart’s and Instacart’s grew rapidly.[50] A more recent study explains that, while Amazon’s share of online grocery is hard to estimate, several rivals (Walmart Grocery, Shipt, Peapod, and Instacart) grew significantly between 2018 and 2021,[51] with some data suggesting that their growth outpaced that of online-grocery sales as a whole.[52] While all of this should be taken with a grain of salt, the initial picture we get is certainly not one of Amazon excluding rivals and dominating either the world of physical retail or that of online-grocery sales.

This overall assessment is corroborated by more anecdotal evidence suggesting that the Whole Foods deal has failed to live up to expectations. For a start, Amazon’s executives have often been compelled to defend the deal against suggestions that Amazon overpaid and that the deal had failed.[53] As one piece surmised:

The success of the Whole Foods acquisition is difficult to measure because Amazon rolls its sales into the physical stores category, alongside its 60 Amazon Fresh grocery stores, an Amazon Style clothing store and 25 smaller Amazon Go stores. But Whole Foods is by far the biggest individual contributor in the group.

Earlier this year, things looked a little bleak. Days after Amazon missed estimates for its first-quarter earnings results, the company announced the closure of six Whole Foods stores.

As consumers get back into the habit of shopping in person, Whole Foods is showing signs of recovery. Placer.ai found the number of visits people make to Whole Foods is now hovering at about the same level as July 2017, before Amazon took over.[54]

Of course, some may retort (fairly) that rivals might have performed even better absent the merger, but that is not the harm that critics were predicting when the deal was cleared. Instead, they claimed that many of Whole Foods’ rivals would go out of business, and that Amazon would also dominate online-grocery retail. That simply was not the case.

Looking at the direct effects of the merger on Whole Foods’ business model, we see many innovations. One of the most notable changes was the introduction of lower prices on a selection of Whole Foods products, with Amazon Prime members receiving even deeper discounts.[55] This move aimed to make Whole Foods’ prices more competitive with other grocery stores, and it helped to increase foot traffic in stores.

In addition to lower prices, Amazon also introduced new technologies to Whole Foods stores, such as the use of cashier-less checkout systems[56] and in-store pick-up for online orders.[57] They’ve even introduced entire stores without checkout lines.[58] Whole Foods also began offering a wider selection of products through Amazon’s online marketplace.

The merger also had an impact on the broader grocery industry. Other major retailers, such as Walmart and Kroger, responded by also cutting prices and increasing their online-grocery offerings.[59] Kroger’s partnership with Ocado marks a major shift in the grocery industry. Through this collaboration, Kroger will be able to benefit from Ocado’s robotic technology for packing orders placed online.[60] Similarly, Target has tried to stay up to date with emerging technologies with its $550 million acquisition of Shipt, a startup offering same-day delivery services.[61]

Walmart followed suit by acquiring Parcel, another startup that offers same-day delivery services, and has announced a partnership with Alert Innovation, which employs automated carts to fulfill grocery-pickup orders at stores. Walmart first introduced grocery pickup in 2017 and initiated a harder push starting in 2019.[62] In 2018, the company also introduced same-day grocery delivery.[63] It’s hard to square these developments with Lina Khan’s prediction that the Whole Foods deal “would allow Amazon to potentially thwart future innovations.”[64]

The point is not that the Amazon-Whole Foods merger was the sole cause of these innovations. They required technological innovations that are separate from anything related to groceries. The important takeaway is that the grocery market continues to innovate, particularly in the direction of online orders and rapid delivery. These are exactly the areas in which Amazon specialized and was expected to bring to Whole Foods with the merger. Despite Stacy Mitchell’s claim that “delivery is key to sustaining a monopoly online” or that Amazon can “control rapid-package delivery,” it appears today that delivery is just another part of the competitive process, and all the players realize they need to offer the service. Lina Khan’s prediction that “]b]y bundling services and integrating grocery stores into its logistics network, the company will be able to shut out or disfavor rival grocers and food delivery services” has not panned out.[65]

The reality of the grocery market is that competition has increased, as retailers like Walmart, Kroger, Giant, Harris Teeter, and others have expanded their delivery offerings. Similarly, delivery companies like Instacart, DoorDash, and UberEats have also expanded their offerings to include groceries. This has led to the emergence of successful startups in the grocery-delivery market, such as Thrive Market. As a result, consumers now have more options for convenient and efficient grocery delivery, while retailers and delivery companies are adapting to meet the market’s demands.

All of these efforts demonstrate how traditional grocers are embracing new technologies in order to keep up with the ever-changing digital landscape and remain competitive in the market. These technological improvements allowed grocers to be better positioned for grocery pickup at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, online sales for Walmart grew 74% in the first quarter of 2020.[66]

C. In Retrospect

Although it is still too early to draw any firm conclusions, it seems that the merger’s anticompetitive potential was dramatically overplayed by its opponents. Most of Amazon’s direct rivals are still making healthy profits (as reflected by their stock prices). This is inconsistent with the vertical-foreclosure and predatory-pricing stories put forward by critics. Under vertical foreclosure, rivals are deprived of key inputs (or outputs) that prevent them from competing. Predatory pricing occurs when a dominant firm prices below cost in the hope of recouping its losses once rivals have exited the market. Crucially, both of these scenarios necessarily imply that the bottom lines of rivals will suffer (ultimately falling to zero). At the time of writing, these theories have failed to pan out.

Of course, just because anticompetitive scenarios have not yet transpired does not guarantee that they will not occur in the future. Likewise, rivals’ overall profits may conceal losses in those markets where they actually compete with Amazon. Finally, it is possible that these rivals’ profits would have been higher still had the merger not gone through. Although these potential counterarguments might deserve some attention, they do not detract from the inescapable conclusion that, as of yet, Amazon has not managed to exclude any of its large retail competitors thanks to its acquisition of Whole Foods.

More fundamentally, it is important not to lose sight of the other side of the coin: Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods may have generated important benefits that critics failed to consider. First and foremost, Amazon immediately implemented a number of price reductions following the deal.[67] It also started to harness the various synergies that existed between itself and Whole Foods. It notably made some of Whole Food’s items purchasable on Amazon, and placed Amazon lockers in numerous Whole Foods stores (allowing consumers to pick up packages from these locations).[68] The online retailer also ensured that its Prime members would receive various discounts when they visit Whole Foods stores.[69]

And thanks to the forces of competition, the benefits extend beyond Amazon and Whole Foods stores. Rivals notably reacted to the merger by replicating these cost reductions and innovative services. Walmart concluded a deal with Google to allow users to make purchases using Google’s voice assistant.[70] Kroger decreased its prices and expanded its delivery service.[71] And Target introduced a same-day delivery service.[72] Of course, some of these changes would have happened anyway—grocery delivery was always going to gather momentum thanks to consumers’ ever-improving access to the internet. It is also fair to assume, however, that Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods accelerated this trend by signaling to rivals they needed to up their game rapidly, or Amazon-Whole Foods might ultimately eat their lunch.

Of course, it is hard to tell whether these benefits would have been achieved without the Amazon-Whole Foods merger. Amazon could conceivably have concluded a long-term contract with Whole Foods, leading rivals to introduce their improvements regardless of the merger. But this is far from certain. As Benjamin Klein, Robert Crawford, & Armen Alchian famously pointed out, long=term contractual relationships sometimes entail significant practical obstacles.[73] The upshot is that it is often more cost-effective for firms to opt for an outright merger. And if a merger was indeed necessary to generate synergies between Amazon and Whole Foods, then there is little doubt that it also played some part in the competitive response of rivals. In short, there are strong reasons to believe that Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods may have caused some of the benefits that U.S. retail consumers currently enjoy.

In short, many critics’ response to the Amazon-Whole Foods merger was simply kneejerk antitrust populism. Nothing at the time of the merger—other than a presumption that big is bad and a dystopian fear that big firms inevitably continue to increase their market shares[74]—justified the doomsday scenarios that were bandied about. This, among many other factors, is why the FTC ultimately allowed the merger to proceed without a protracted in-depth investigation.[75] Five years on, this decision appears fully vindicated, and critics’ arguments appear even more unreasonable with hindsight. The doomsday scenario failed to transpire.

II. Consolidation in the Beer Industry

The beer industry has undergone significant changes in the 21st century, with a shift towards craft beers, an increase in the number of microbreweries, and a growing interest in different styles of beer. In the early 2000s, the industry was dominated by a small number of large multinational corporations, but over the past two decades, a wave of small, independent breweries has emerged, challenging the status quo and changing how consumers think about beer.

At the same time, there has been a reshuffling of ownership among the biggest U.S. brands: Anheuser-Busch, Miller, and Coors. In 2002, South African Brewing (SAB) acquired Miller Brewing to become SABMiller. In 2005, the Canadian brewing company Molson merged with Coors to become Molson Coors. In 2007, SABMiller and Molson Coors announced their “joint venture.” In 2008, InBev (itself a merger between the Belgian firm Interbrew and the Brazilian conglomerate AmBev) acquired Anheuser-Busch to become AB InBev or just ABI. In July 2016, ABI acquired SABMiller after approval from antitrust authorities. The deal included commitments from ABI to divest SABMiller’s 59% equity stake in Molson Coors. Given this list of major mergers within the space, it is appropriate to consider both the effects of specific mergers and also the general trends.

A. The Predictions

While the earlier mergers were relatively underdiscussed, the final ABI-SABMiller merger received significant attention from antitrust watchers and commenters in the ABI-SABMiller merger process. The American Antitrust Institute warned that the merger would “eliminate competition,”[76] “impose significant price increases on consumers,” and “undermine the continued emergence of craft beer.”[77] AAI President Diana Moss told the Washington Post that the deal was “a terrible, terrible idea” and that “[t]his should be dead on arrival at the DOJ. There would be grave concerns over their power to control price … and the effects on the craft-brewing industry would be devastating.” President Biden’s 2021 executive order on competition singled out several sectors, including alcoholic-beverage production, as embodying apparently problematic concentration and a weakening of competition.[78] The U.S. Treasury Department report created in response to the executive order claimed that “[s]ome of the increased concentration may have resulted from the absence of consistent merger enforcement.”[79] While these claims are much less extreme than those we find in other contexts, it is still worthwhile to evaluate how reasonable they were and what evidence we have at this point about the effects of consolidation in the beer industry, to the extent that it has happened.

B. What Happened?

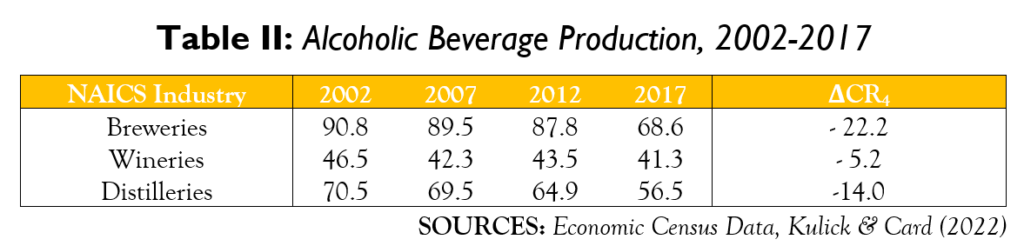

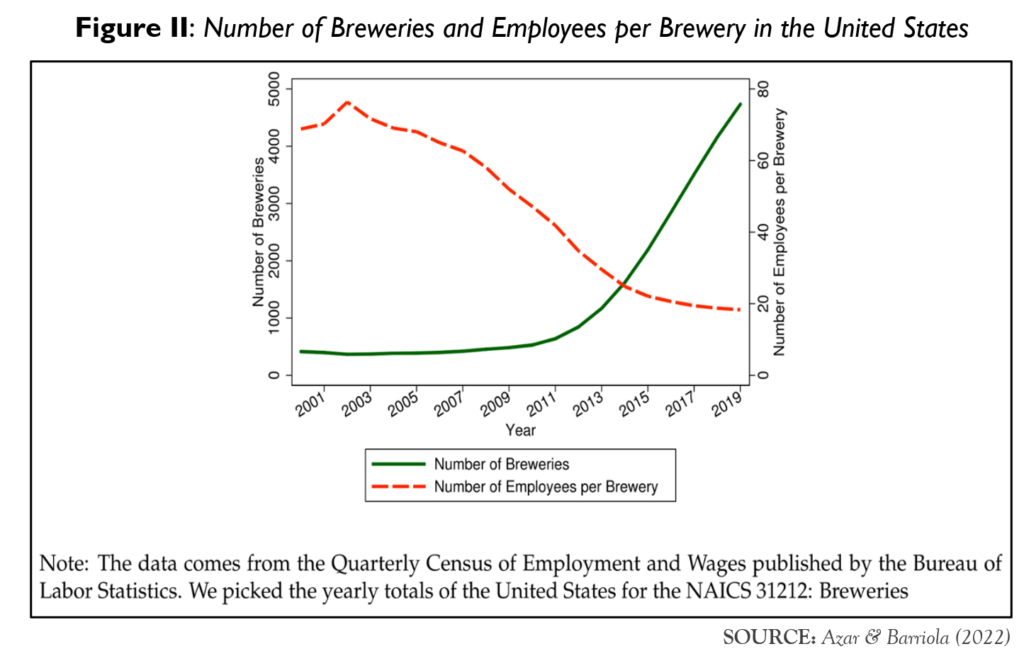

First, has concentration been rising in beer? The Treasury report assessing competition in the beer market asserts that concentration is rising.[80] It is unclear what period was under consideration, although the citations are to older literature from the early 2000s. A recent study by Kulick & Card using U.S. Census data suggests otherwise.[81] They consider the concentration for the four largest firms in the industry. For breweries, that number was 90.8% in 2002, but has fallen to 68.6% in 2017, which is the most recent data. Instead of rising concentration, as commonly asserted, we actually see falling concentration within all alcoholic-beverage sectors, with the largest drop in beer brewing.

It is quite possible that those declines in concentration would have been even greater but for the mergers, but the falling concentration is an important datapoint to understand in this discussion.

If we want better identified estimates, we need to look at specific mergers and events. The ABI-SABMiller merger is too recent for the economics-publishing process, but the merger with the best econometric evidence is SABMiller and Molson Coors. SABMiller and Molson Coors announced their “joint venture” in October 2007 and was approved in June 2008. At the time, Miller had a 17.52% market share and Molson Coors had a 10.43% share.[82] Despite growing craft brewers, even at the time, almost 90% of beer revenue was from lagers.[83] In addition to high concentration, the main products were seen as close substitutes (Miller Lite and Coors Lite, for example).

Despite these possibly worrisome features of the market, the parties claimed large efficiency gains that would offset the market-power increases. The DOJ stated publicly that, in its investigation, “the Division verified that the joint venture is likely to produce substantial and credible savings that will significantly reduce the companies’ costs of producing and distributing beer.”[84] The reason was that “[p]rior to the merger, Coors was brewed in only two locations, whereas Miller was brewed in six geographically dispersed locations. The merger was expected to allow the combined firm to economize on shipping costs primarily by moving the production of Coors beer into Miller.”[85]

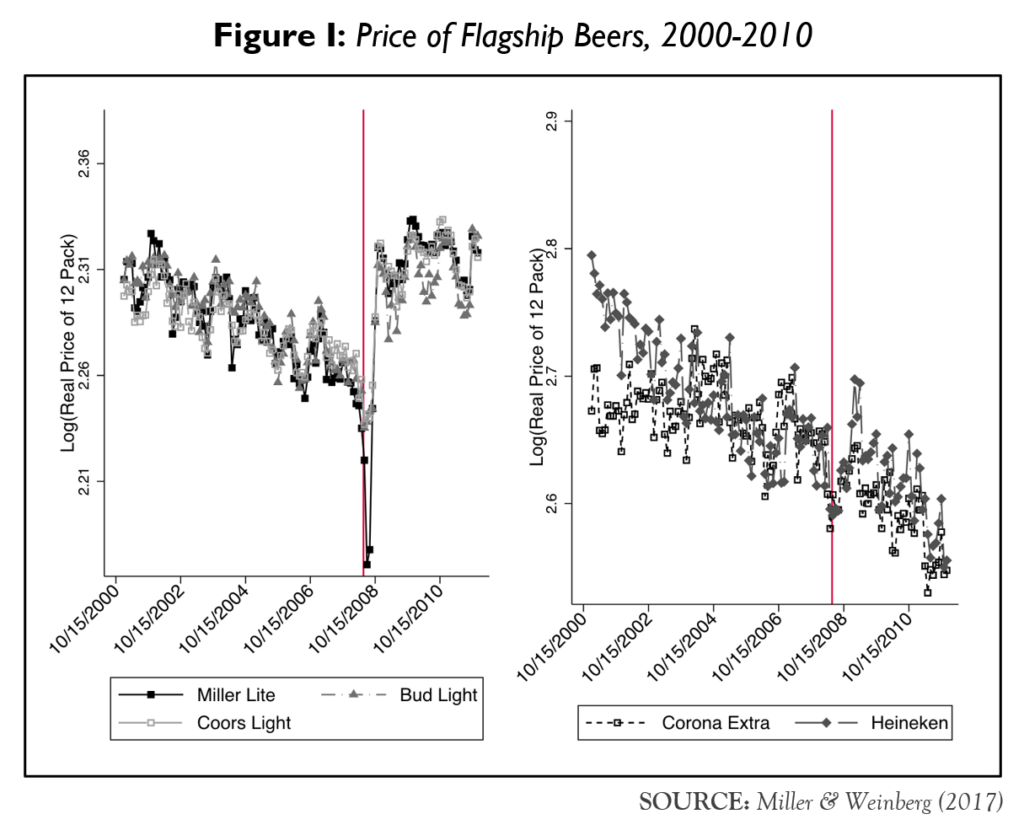

Ashenfelter, Hosken, & Weinberg (2015) use retail-scanner data collected by IRI.[86] The data used was only for supermarkets, which Ashenfelter, Hosken, & Weinberg estimate accounted for 23% of total sales for 2011. They have data on brand, package size, and container type. They find that the concentration effect was roughly (but not completely) offset by the efficiency effect. In their preferred specification, the increase in concentration from the merger was predicted to increase by 2% across all lager-style beers but that was nearly offset by efficiency created by the merger.[87] Overall, prices were unchanged on average.

If we focus on specific beers, Miller & Weinberg (2017) find a significant price increase (6%-8%) after the merger for the most popular beer brands (Coors Lite, Miller Lite, and Bud Lite) but no effect for Corona Extra and Heineken, which are seen as more differentiated.[88] The authors take this as evidence of a coordinated price effect between ABI and Miller-Coors, since the market now had only two major players, compared to three before the merger. Looking at a local level, Ashenfelter, Hosken, & Weinberg (2015); Miller & Weinberg (2017); and Azar & Barriola (2022) all find a positive correlation between increases in HHI and price increases. Overall, there is credible evidence that the merger led to a price increase for the flagship brands.

However, before we conclude that the merger was disastrous for the beer market, remember that concentration has been falling. That is because the big three are not the only players. Azar & Barriola (2022) study the effects of the merger on the craft-beer market.[89] They find that, in the average market over the four years following the merger, the merger led to over an 11% increase in the number of craft brewers, while the number of products per craft brewer remained the same. Since most of these entrants were small, the market shares were largely unaffected by entry. They point to the price increases as the driver of entry into the craft market, as it made entry profitable. This goes against a common theory that larger firms with more power will deter entry.[90] Another possibility, unexplored but consistent with higher entry, is that the merger increased the possibility that craft beers would be acquired by the large brewers.

At the same time, the large breweries are acquiring smaller breweries and changing their production process. For example, according to Elzinga & McGlothlin (2021), when ABI acquired Goose Island, there was a large increase in sales of craft beers, suggesting some sort of spillover from the big names to the craft beers.[91]

C. In Retrospect

Overall, the effects of beer mergers seem to be neutral. While the prices of Coors Lite, Miller Lite, and Bud Lite increased, efficiency gains meant that the average price stayed flat, and we saw new entry from craft brewers. Continued growth in craft brewing suggests that Diana Moss’ concern that “the effects on the craft-brewing industry would be devastating” appear not to have panned out. One thing that makes predictions about the ABI-SABMiller merger hard to assess in retrospect, however, is that many came before the spin-off of Coors was finalized as part of the deal. It is possible that these concerns were conditional predictions that did not ultimately apply, as SABMiller needed to divest from Molson Coors as part of the DOJ agreement.

One aspect that affects the study of mergers in the beer market is that the alcohol market is extremely regulated, and those regulations change over time. Differences in regulatory regimes can serve to distinguish alcohol markets across states and over time, which makes it easier to compare more and less concentrated markets. At the same time, changing regulations also contaminate any causal analysis. The regulations introduce pressures to beer markets that differ from more standard product markets, such as smartwatches. As Barry Lynn of Open Markets described it: “The great effervescence in America’s beer industry is largely the product of a market structure designed to ensure moral balances…” (emphasis added).[92] He added that “consolidation can also threaten the primary outcome of this market — the ability of communities and individuals to manage for themselves this ever so extraordinary commodity.”[93]

Such moral questions, or questions about communities’ ability to manage themselves, are beyond the scope of this merger retrospective, but an unavoidable part of the larger policy debate surrounding beer.

III. Bayer-Monsanto

The Bayer-Monsanto merger, completed in 2018, brought together two of the world’s largest and most innovative agricultural companies, creating a leading player in the industry. The merger, valued at $66 billion, has had a significant impact on the global agriculture industry and brought several benefits to farmers and consumers. After earning approval from the European Union, Russia, and Brazil, approval in the United States (particularly by the DOJ) was the deal’s final hurdle.

In order for the Bayer-Monsanto merger to pass, the DOJ required the companies to make certain divestitures. Divestitures are the process of selling off certain assets or businesses in order to mitigate concerns about the merger reducing competition in the market. The DOJ required Bayer to divest certain seed and herbicide assets in order to address concerns about the merger’s potential impact on competition in the seed and herbicide markets. In total, the two companies spun off $9 billion in assets.[94] Specifically, Bayer was required to divest its cotton, canola, soybean, and vegetable-seed businesses, as well as its Liberty herbicide business, to BASF, a German chemical company. This divestiture helped to ensure that there would continue to be strong competition in the seed and herbicide markets after the merger.

Additionally, Bayer was also required to divest certain assets to ensure that there would continue to be competition in the digital-agriculture market. Specifically, the company was required to divest its “Xarvio” digital-agriculture platform to an independent third party.

The DOJ also imposed restrictions on Bayer’s behavior to ensure that the company would not use its strengthened position in the market to harm competition. For example, Bayer was required to license certain intellectual property to competitors to ensure that they could continue to compete effectively.[95] These required divestitures and restrictions on behavior helped to ensure that there would continue to be strong competition in the market after the merger.

A. The Predictions

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the merger drew stern rebukes from progressive advocates of more aggressive antitrust enforcement. Spencer Waller, a professor at Loyola University Chicago’s School of Law and the director of the Institute for Consumer Antitrust Studies, expressed standard fears about the merger: “The fear is that price is going to go up, quality is going to go down, and whichever company was trying super hard before, well, they got merged in, and they’re going to stop caring.”[96] Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) opined that “[l]arge-scale consolidations in the agricultural inputs sector could also significantly reduce competition, limit seed options for farmers, and raise prices for both farmers and consumers,” adding that the “company created by the Bayer-Monsanto merger would control about 24 percent of the world’s pesticides sales. Together, Bayer-Monsanto and Dow-DuPont would control 76 percent of the market for corn and 66 percent of the market for soybeans.”[97] These fears were echoed by academic work arguing that increased consolidation resulting from the Bayer-Monsanto and Dow-Dupont mergers would lead to significant price increases in the markets for corn, soy, and cotton seeds.[98]

More generally, the merger (as well as others deals in the food sector) was repeatedly cited as an example of the failing state of antitrust enforcement. For instance, the Democratic Party’s “Better Deal” platform, published in July 2017, cited the food sector as one of five key sectors that required more stringent antitrust merger enforcement.[99] It also argued that the Dow-Dupont, Bayer-Monsanto, and Syngenta-ChemChina mergers would harm farmers and rural communities. According to the document, these harms justified a more holistic approach to antitrust policy.[100]

Finally, in addition to standard market-power concerns, some critics raised fears about the use of data to harm farmers. Margrethe Vestager, the European Union’s top antitrust enforcer at the time of the merger, worried about the effects of collected data on farms. “Digitalization is radically changing farming,” Vestager told a German newspaper. “We need to beware that through the merger, competition in the area of digital farming and research is not impaired.”[101] “If they own the data, then they can dictate what they plant, where they plant it, and how they’re harvested,” said Joe Maxwell, executive director of the Organization for Competitive Markets.[102]

B. What Happened?

The merger did increase market concentration within the agriculture industry. Prior to the merger, Bayer and Monsanto were already two of the industry’s largest players and the merger served to further consolidate their position. Increased concentration led to concerns about reduced competition and higher prices for farmers and consumers. But did they play out?

While people will point to rising seed prices as evidence of the merger’s harms, it is important to view the rising prices in context. Several factors, unrelated to any mergers, contribute to the rising cost of seeds over time. One reason is the ongoing development of hybrids that have higher yields, making the seed more valuable. Additionally, the incorporation of biotechnology traits in corn hybrids has provided farmers with management advantages, such as possible reductions in the use of pesticides and tillage, which further increases the value of the seed.[103] Improvements in seed genetics and technology have led to increased costs of seeds, specifically, but may reduce the true costs of corn per-bushel, as yields have increased.[104]

In addition, the merger has led to concerns about the potential for the newly merged company to wield significant influence over the regulatory process. The company will have significant resources at its disposal, which could be used to influence regulators and shape policies in ways that benefit the company, but not necessarily the public.

Regulators argued that, by merging with Monsanto, Bayer would become a major player in the corn-seed market. The newly merged company would have significant market share and an increased ability to influence prices. Additionally, since Bayer also sells a key seed treatment to corn farmers, the company would have an incentive to raise the price of the treatment, knowing that farmers would have fewer choices of seed suppliers, which was one of the concerns that the government raised about the merger. This argument ignores the complementarity between seeds and seed treatment, in that any increase in price for seed treatment lowers the demand for your seeds. The merger actually aligned these incentives.

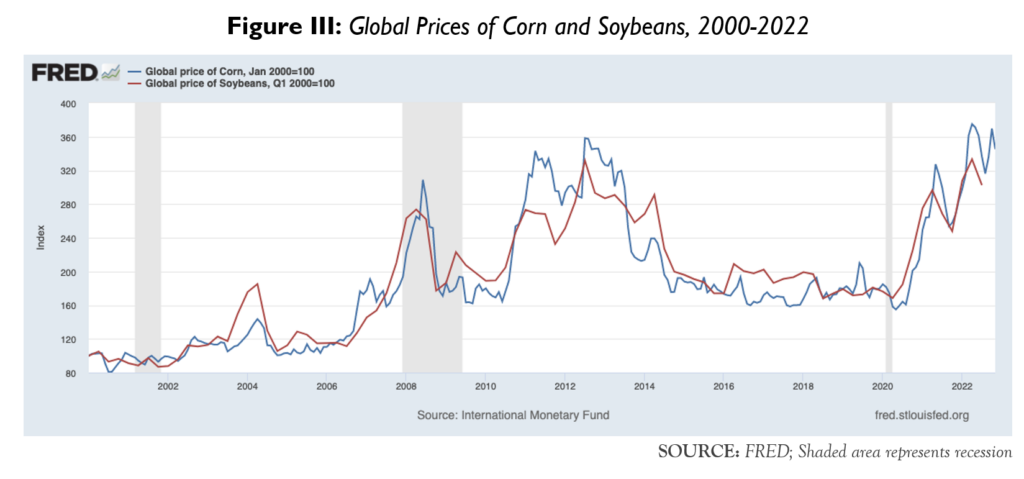

One market where Monsanto had relatively large market share is in corn and soybean seeds. Sen. Klobuchar worried that “Bayer-Monsanto and Dow-DuPont would control 76 percent of the market for corn and 66 percent of the market for soybeans.” While hardly rigorous econometric evidence, we can look at global corn and soybean prices, as shown in Figure III, to assess how the corn and soybean markets are doing. Both prices stayed steady after the merger, but these prices are not adjusted for inflation. Corn and soybean prices actually fell in real inflation-adjusted terms. Only the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the ensuing inflation and supply-chain issues, drove corn prices back on par with previous nominal highs from around 2012-2013.

Among the primary benefits of the merger have been increased efficiency and cost savings. By combining the resources and expertise of both companies, the newly merged company is better positioned to invest in research and development, improve yields, and reduce costs for farmers. In 2018, along with the acquisition of Monsanto, Bayer announced annual cost savings of around $1.5 billion.[105] In 2020, it announced an addition $1.8 billion in annual savings.[106] It is important to note, however, that this latter cost savings was partially in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and should not be directly attributed to the merger.

These sort of cost reductions do, however, tell us something about the relevant markets, as well as the market position in which Bayer now finds itself. The need to cut costs drastically does not comport with a firm soaking in monopoly profits. If the best of all monopoly profit is a quiet life, Bayer does not have that life. Over the past five years, since just before the merger was allowed, Bayer’s stock is down more than 50%.

C. In Retrospect

Five years after the merger, there is no evidence that Bayer can “dictate what they plant, where they plant it, and how they’re harvested.”[107] Again, the direst predictions have not occurred. Farming remains a difficult life. The hours are long, and prices are volatile. But it is hard to find a break in any trends.

One of the challenges of a retrospective on the Bayer-Monsanto deal is the sheer variety of markets in which each company participates. This is a broader issue that applies to any retrospective analysis of mergers. We need to be careful that any perceived market harms are not actually the result of random chance. Even if most mergers are beneficial for competition, some will turn out to have generated a rise in prices. This is not conclusive evidence that allowing the merger was a mistake, even if it may appear so in hindsight. It is quite possible that at least one of the many markets affected by the Bayer-Monsanto merger did see a rise in prices. But looking across those many markets to find the particular one that generated a price rise is equivalent to p-hacking. We have the same problem in looking explicitly for markets where harm did not occur.

Instead, this retrospective focused on Bayer’s overall market position, as reflected in its stock returns and need to cut costs, as well as the market for corn and soybean seeds, because these were markets that were explicitly highlighted as areas of potential concern by progressive critics. Looking at these metrics suggests that, despite an increased level of market power from the merger, Bayer has failed to raise prices or exploit its position in any meaningful way.

IV. Google-Fitbit

Google’s purchase of Fitbit was one of the largest tech acquisitions of 2019. The $2.1 billion deal marked Google’s entry into the wearables market and added Fitbit’s popular fitness-tracking devices to the tech giant’s portfolio.[108] The acquisition also sparked a debate among industry experts, privacy advocates, and consumers regarding the potential consequences of combining the vast data collected by Fitbit with Google’s already extensive data-collection and analysis capabilities.

A. The Predictions

The deal’s announcement was swiftly met with cries of alarm from both privacy advocates, who feared it would enable Google to use consumers’ health information to target ads, and from progressive-minded competition scholars, who believed the deal would cement Google’s market position in online advertising. Lina Khan called allowing the acquisition a “terrible decision.” This was part of her larger complaint that “[e]nforcers spent the last two decades waiving through hundreds of acquisitions by Google, only to watch it illegally renege on commitments, exclude rivals, & monopolize markets.”[109]

The fears surrounding the Fitbit acquisition are perhaps best summarized in a joint statement, signed by several consumer associations and progressive-advocacy groups, including BEUC (Europe’s largest consumer organization), the Open Markets Institute, and the Omidyar Network.[110] Among other things, the organizations claimed the merger would prevent new firms from entering the market and would harm consumer privacy:

Wearable devices could replace smartphones as the main gateway to the internet, just as smartphones replaced personal computers. Google’s expansion into this market, edging out other competitors would thus be significant. Wearables like Fitbit’s could in future give companies details of essentially everything consumers do 24/7 and allow them to feed digital services back to consumers…. The exploitation of such data in a commercial context is an important concern that demands close scrutiny by regulators both for its anticompetitive effects (where huge bundles make it near-impossible for entrants to compete against incumbents) and anti-consumer effects (creating ever bigger bundles that undermine consumer choice).[111]

Along similar lines, Tommaso Valletti & Cristina Caffarra intimated the deal would enable Google to use data from Fitbit devices in order to better target its ads. According to them, this would harm user privacy and suppress competition from other advertisers:

With Google as the acquiror, the concern is that the acquisition is intended to pre-empt the emergence of a potential rival who could otherwise develop by exploiting a key ‘access point’ for the collection of data and for access to our attention, with the ultimate aim to defend and enhance its position in the core advertising business…

[Google] already owns locational data that is hugely important for targeted advertising…. Combining this existing stock with enormously valuable biometric and behavioural data that can inform on other dimensions of the user’s experience, Google will gain further strength in the supply of digital advertising in which it is already super dominant.[112]

In both cases, an important part of the argument was that the merger would harm competition because data from Fitbit devices would reinforce Google’s already strong position in the online-ad industry.[113] The authors supported this assertion by claiming essentially that the incentives to do so were simply too powerful for Google to ignore:

Google/Fitbit involves the acquisition by a giant digital platform—whose business is based on the monetisation of customers’ data through microtargeted ads, and is already sitting on a mountain of personal data and analytics capabilities—of a target with unique data-generating assets in the most sensitive of all areas: capturing biometric data (health, and even emotions) 24 hours a day, every day.[114]

Or, as seven Democratic senators claimed:

Adding Fitbit’s consumer data to Google’s could further diminish the ability of companies to compete with Google in… ad technology markets and could raise barriers for potential competitors to enter these markets,’ the lawmakers wrote.[115]

Others, including Gregory Crawford, speculated that Google would combine health data from Fitbit devices with more general data about those same users, and sell this to insurance providers, enabling them to better price discriminate between consumers:

Combining health and non-health data will allow Google to use non-health data to “customize” insurance offers. Does he gamble? Does she search for symptoms of life-threatening illnesses? It’s easy to see how such info could reduce the quality of insurance offers.[116]

Regulators, however, were largely unconvinced by these claims, with the world’s largest antitrust authorities clearing the merger with only limited remedies. In the United States, the DOJ essentially waved the deal through, while the European Commission required only limited API access and data-use-related remedies.[117]

In short, vocal critics made three key claims about the merger, all of which have since turned out to be false: (i) that Google would use data from Fitbit devices to better target its ads, (ii) that Google would obtain a dominant position in wearable devices and prevent the entry of rivals in this segment, and (iii) that Google would reinforce its already strong position in the online-advertising market. As explained below, not one of these claims has turned out to be even remotely accurate.

B. What Happened?

Critics’ claims appear most mistaken in the advertising industry. Indeed, the fear was that, by purchasing Fitbit, Google would be in a position to better target ads throughout its entire platform, thereby increasing its hold on the broader advertising industry. Four years on, however, the opposite appears to have happened. From 2017 to 2022, Google’s share of online advertising spend has steadily declined, falling from 34.7% to 28.8%.[118] And it is not just in relative terms; the company’s quarterly earnings reports show a clear decline in ad revenue, including year-over-year drops in the fourth quarter of 2022 of 8.6% for the Google network and 7.0% for YouTube.[119] As usual, critics may retort that Google’s revenues and market shares would have declined even more absent the merger but, once again, that was not the initial claim. Instead, they wrote that the merger would give Google an unbreakable grip on the online-advertising industry—the “horse has bolted” as Gregory Crawford put it[120]—and that has not been the case.

A second major piece of the doomsday claims concerns the combination of health-related data from Fitbit with Google’s other data concerning its users, either with the purpose of using it for Google ads or in order to sell it to insurers. While the remedy imposed by the European Commission precluded Google from combining data across platforms with the purpose of selling Google ads, it said nothing about the use of Fitbit and Google data for insurance purposes.[121] Meanwhile, nothing prevented Google from doing any of this in the United States, where the DOJ chose not to challenge the acquisition.[122] And yet, at the time of writing, even in the United States, Google does not use Fitbit data to target Google Ads. Fitbit’s privacy policy is unambiguous in this respect. The “how we use information” section of the policy lists only four uses:

PROVIDE AND MAINTAIN THE SERVICES…

IMPROVE, PERSONALIZE, AND DEVELOP THE SERVICES…

COMMUNICATE WITH YOU…

PROMOTE SAFETY AND SECURITY…[123]

None of these categories (which the privacy policy delves into in great detail) could reasonably be construed as entailing the use of Fitbit data in order to better target Google ads. The same applies to the “how information is shared” section of the same privacy policy.[124] In short, Google does not use Fitbit data to target Google ads. As the company summarized in an explainer regarding the merger:

Currently, all customers log in to Fitbit with a Fitbit account, and so your Fitbit data syncs to your Fitbit account, not to a Google account. However, you may still choose to transfer some Fitbit data to Google in limited cases, like if you use Fitbit with a Google service. For example, you may authorize Google Assistant to provide your Fitbit activity, like your step count and calories burned. For more information on connecting Fitbit and Google Assistant, please see How do I use a voice assistant on my Fitbit smartwatch? and the related Google help article. For more information on how Fitbit shares data with others, including Google, please see the Fitbit Privacy Policy section titled “How Information Is Shared.”[125]

Thus, contrary to critics’ claims, Google does not integrate users’ Fitbit data into its broader advertising platform, nor does it share (or sell) that information with (to) insurers.[126] And nothing suggests it plans to do so in the future.

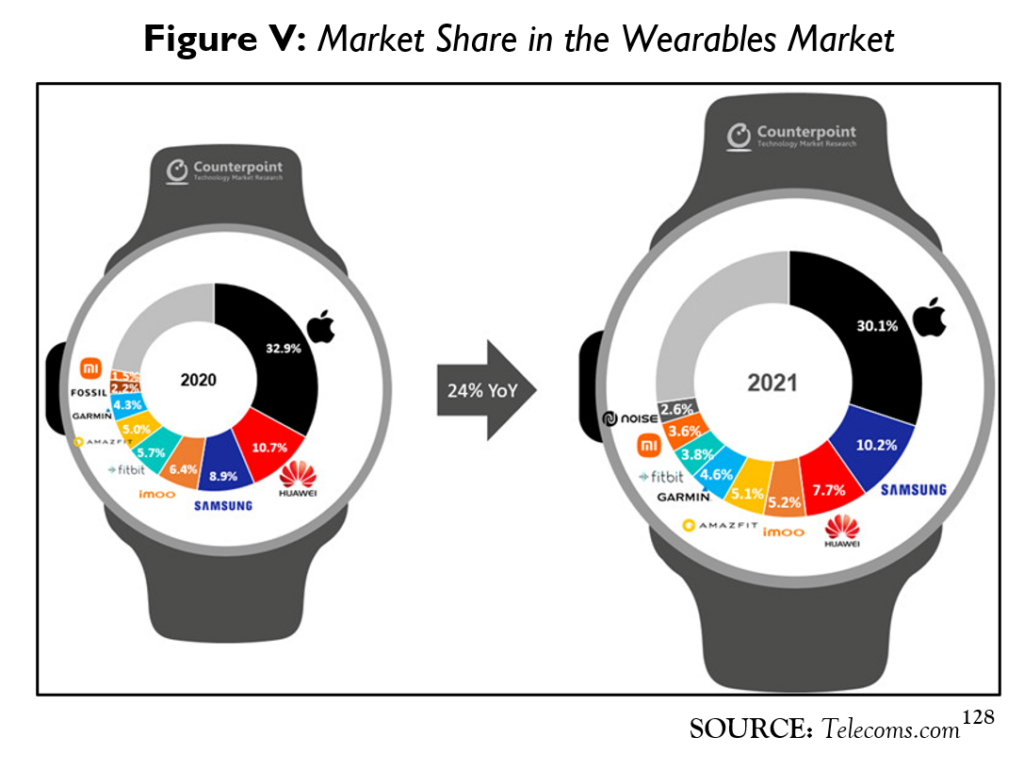

This leaves one final question: did the acquisition of Fitbit enable Google (and Fitbit) to significantly increase either of the firms’ market position in the burgeoning wearable-device industry? Once again, critics’ claims appear to fall short. Fitbit has been slowly losing market share. According to Counterpoint Technology Market Research, the overall smartwatch market grew by 22% from 2020 to 2021, but Fitbit’s share fell from 5.7% to 3.8%, as shown in Figure v. Counterpoint found similar declines in market share from 2021 to 2022.[127] Other competitors, such as Samsung and Garmin, saw an increase in their market shares, but Apple (rather than Google-Fitbit) remains the major player in the market by a substantial margin.

C. In Retrospect

It is important to situate the Fitbit acquisition in a broader tech-hardware market that all of the major players are trying to enter. One year after the relevant merger took place, Amazon introduced its Amazon Halo, which it describes as “a new service dedicated to helping customers improve their individual health and wellness. Amazon Halo combines a suite of AI-powered health features that provide actionable insights into overall wellness via the new Amazon Halo app with the Amazon Halo Band, which uses multiple advanced sensors to provide the highly accurate information necessary to power Halo insights.”[129]

Many argued at the time that Amazon’s invention would become one of the biggest game-changers in the market for smartwatches. Nevertheless, two years after its launch, the Halo had not set the sales charts on fire and, in July 2022, the company cut its price steeply to $45. It continues to stand as a cheaper alternative to more entrenched producers. Market watchers saw Amazon’s struggles as similar to Fitbit’s, with one tech-news site noting: “The Fitbit comparisons are immediately obvious, given the similar design and form factor.”[130] Yet, neither cheaper option has been able to supplant the Apple Watch.

It is also important to note that the Google-Fitbit merger helped enable Google to enter the smartwatch market to compete with the market leader, Apple. And the Fitbit acquisition was not the only move Google made aimed at competing with its biggest smartwatch rival: In 2019 Google also acquired Fossil Group’s smartwatch-related IP and a portion of its R&D personnel.[131] Google introduced the Pixel Watch in late 2022, following two failed previous attempts (both cancelled ahead of their release) to introduce a Pixel-branded smartwatch to compete with the Apple Watch.[132]

Why did Google take so long to build a smartwatch? When I asked that question to Rick Osterloh, Google’s SVP of hardware…, his answer was one word: Fitbit. Google couldn’t make the smartwatch it wanted without a killer health and fitness platform, and until very recently, it simply didn’t have one.[133]

There have also been policy changes that have affected the market and particularly the data concerns that some observers raised. Among the significant legislative changes were the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), both of which took effect in in 2018. In 2019, Sens. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) and Jacky Rosen (D-Nev.) first introduced the Stop Marketing And Revealing The Wearables And Trackers Consumer Health (SMARTWATCH) Data Act, which proposes “prohibitions on the use, sharing, or selling of health data collected, stored, and transmitted by wearable devices, including smartwatches.”[134]

Those developments notwithstanding, it appears clear that critics’ fears concerning the Fitbit acquisition were dramatically overblown and failed to reflect the competitive reality that Google faced. With intense competition for wearable devices, integrating Fitbit data into the broader Google Ads ecosystem was always going to be an unpopular move that Google could ill afford. Meanwhile, integrating the Fitbit platform into Google’s smartwatch ecosystem was exactly the needed boost to finally enable it to compete with Apple in the smartwatch space.

V. Facebook-Instagram (and WhatsApp)

Public reaction to the Facebook-Instagram merger (and, to a lesser extent, Facebook’s purchase of WhatsApp) could be seen as the inverse of what happened with the mergers discussed in the previous sections. While many progressives today see this merger as “the one that got away” from authorities, at the time, it was mostly seen as benign and was even derided as a poor business decision on Facebook’s part. Very few competition scholars or advocates of aggressive antitrust stepped forward to assert that it would harm competition. In other words, a deal that is now seen by many as the quintessential “killer acquisition”[135] struck most as harmless when it was announced. As in the previous case studies, this suggests that media coverage and the commentary surrounding a merger is often a poor predictor of its likely future effects on competition—or, at least, a poor predictor of which mergers critics will come to see as harmful in the future.