Vaccine Hesitancy and the Pandemic: Physician Survey Responses

Executive Summary

Vaccines for the SARS-CoV-2 virus saved countless lives and are a modern science miracle. But they had risks, were not as effective as originally claimed, and were effectively forced onto many people in order for them to work, attend school, or travel. There is early evidence that these and other factors may currently be contributing to heightened vaccine hesitancy, with potentially serious consequences for public health.

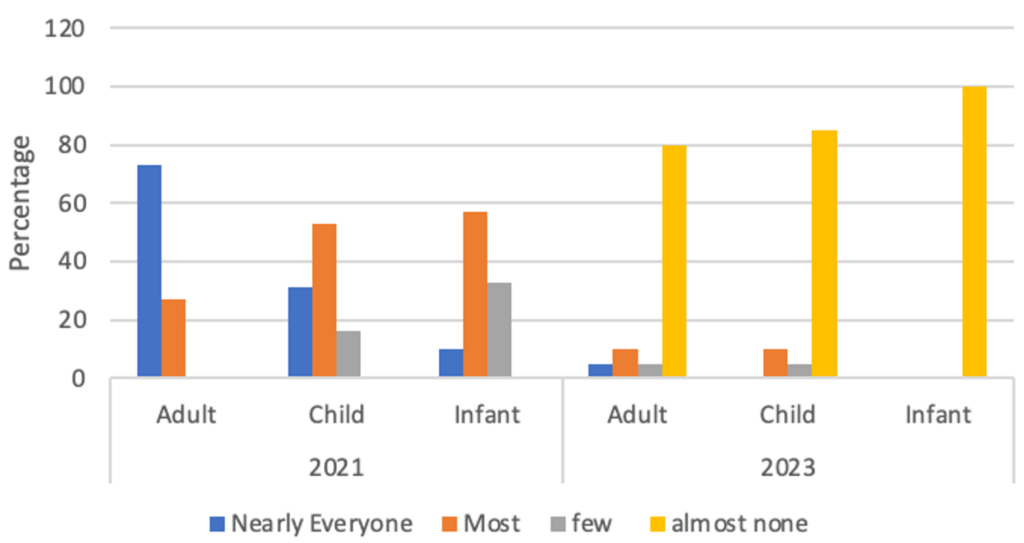

To better understand the extent and causes of vaccine hesitancy, we surveyed 124 physicians in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. They reported that most patients (nearly all adults and most children and infants) took the initial COVID-19 vaccines in the winter of 2021. Take-up among adults declined over the proceeding months and was much lower by the second half of 2023 (and almost non-existent among infants). This shift in vaccine uptake was especially prevalent in the more staunchly Republican-voting areas of Montgomery County. It is noteworthy, however, that at-risk populations continue to receive vaccine boosters.

More worryingly, physicians also report an increase in patient distrust for non-COVID vaccines and a more generalized increase in concern about and distrust of public-health advice among their patients. Even some physicians are concerned about governmental public-health advice.

Future research will need to establish whether vaccine uptake has changed and, if so, how it has changed, and what this may mean for public health. If these data are replicated in larger surveys and a trend becomes identifiable, the implications for public health could be serious, indeed.

I. Background

Vaccines are among the most powerful interventions in the field of public health, plausibly saving and improving more lives than anything other than good sanitation and diet. Historically, however, vaccines have typically taken years to develop. When effective vaccines were developed for COVID within a year of the pandemic’s emergence, many were surprised and awed.[1] Amazingly and, in retrospect, incredibly, the makers of the first mRNA vaccines to be granted emergency use authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) claimed more than 90% efficacy in trials. This is much higher than the efficacy of vaccines for many other diseases,[2] including influenza, although this level of efficacy was expected to wane over time.[3] For all of these reasons, COVID vaccines were greeted as truly remarkable public-health interventions.

Uptake of COVID vaccines was initially very high.[4] This was likely primarily because of the protection they afforded against a potentially deadly disease. But it was also partly because, for many, vaccination became a requirement for work, travel, and most other social interactions.

But concerns about the vaccines soon arose. While many of these purported risks were plainly false,[5] some—most notably, the risk of myocarditis and pericarditis among the young—were supported by data.[6] It also emerged that the vaccines were far less effective and shorter lived than originally touted. Moreover, they do not completely prevent disease transmission, although they probably reduce transmission by reducing viral loads.[7] As the virus has mutated over time, it has generally become more virulent, but less dangerous, which also likely has informed the calculus of those considering whether to take further vaccine boosters.

Despite these concerns, state and federal authorities have recommended and, in many cases, demanded vaccination.[8] These mandates were applied even to those who had just had COVID. This appeared illogical, given that the natural immunity provided by a disease is usually greater than the passive immunity from vaccination. This appears to be true of COVID, as well.[9]

U.S. vaccine policy is comprehensive and promotes vaccinations for all ages.[10] It also continues to promote COVID vaccines for everyone over six months old.[11] But skeptics have claimed all sorts of dangers from the vaccines, and most people report their experiences are that the vaccines really only prevented death for the old, obese, or those with other co-morbidities. This has resulted in reactive vaccine hesitancy, especially in more Republican-leaning areas. We hypothesize that this is partly because many elected Republicans vocally opposed vaccine mandates and some even voted to prohibit private requirements.[12] Such actions likely influenced opinion in these Republican-voting areas.

A. Aims

The aim of this research is to examine vaccine uptake and patient opinions about vaccines in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. If, as expected, COVID-vaccine refusal and more general vaccine hesitancy has increased over the past few years, reasons for this will be discussed.

B. Methods

Primary physicians oversee many vaccinations and also address many questions from patients about vaccines, including about efficacy and safety. We undertook a survey of primary physicians in order to obtain information about changes in vaccine uptake, physicians’ interpretations of patients’ opinions about vaccines, and their own opinions about vaccines.

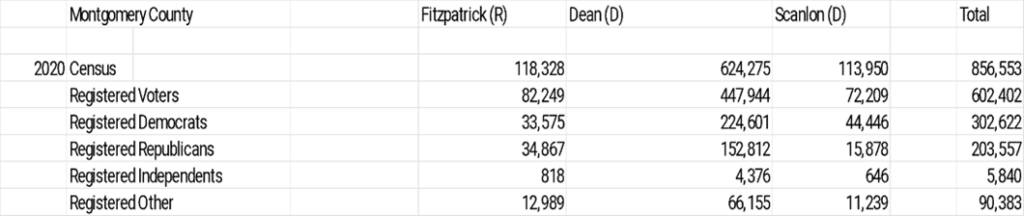

The survey was undertaken in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, which ranges from the Northeast suburbs of Philadelphia into more rural areas. It has three members of the U.S. House of Representatives, including two Democrats (Reps. Madeleine Dean and Mary Scanlon) and one Republican (Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick).

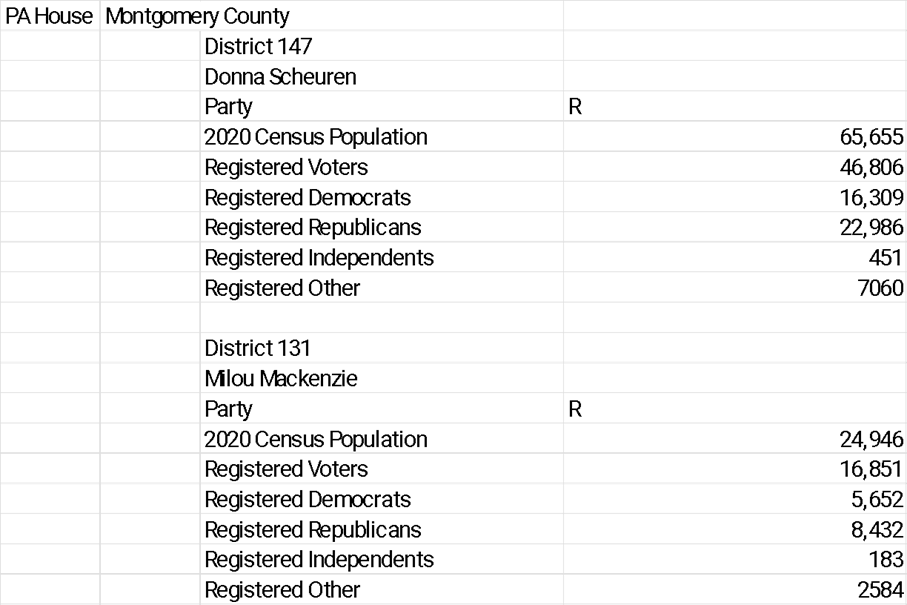

Physicians were surveyed in the three constituencies. To assess uptake of, and opinions about, vaccines across the political divide, it made sense to find the few Republican-voting areas and compare them to the rest. The two most strongly Republican-voting of the county’s14 Pennsylvania House of Representatives districts are District 147 and District 131, both of which have 30% more registered Republican voters than Democrats. In many of the other state House districts, there are more than twice as many Democrats as Republicans registered to vote. From within the overall sample, physicians from these two Republican-leaning districts were compared to the other 12 state House districts. The tables in the appendix show all relevant political data.

C. Survey

The survey, titled “Vaccine Questionnaire” and republished in full below, was kept short to ensure full participation by physicians. It was undertaken for two weeks starting in mid-January 2024, with responses collected online, over the phone, or in-person.

D. Vaccine Questionnaire

The aim of this short survey is to find out about opinions and uptake of key vaccines in your practice. And to note whether there have been changes in either opinions or uptake of vaccines over the past few years.

- How long have you been at this practice (less than four years will not participate in final results)?

- How would you describe the initial uptake (2021) of the COVID vaccine for a) adults b ) children c) infants

Nearly everyone, most, few, almost none

- How would you describe the uptake of the most recent COVID booster for a) adults b ) children c) infants

Nearly everyone, most, few, almost none

- Over the same time period early 2021- late 2023 has uptake of other (non-COVID vaccines) changed in a) adults b ) children c) infants (increased, stayed the same, decreased)

- Have patient opinions changed over this time period?

COVID – positive, the same, negative about the vaccines.

Other vaccines – positive, the same, negative.

- Please provide any specific comments you recall made by patients.

- How have your opinions changed, if at all, about vaccines over the time period?

Thank you for your time.

E. Response Rate

In all, 124 physicians in Montgomery County who had been in their practice for more than four years replied in full to the survey. Rep. Dean’s constituency is the largest, and this was reflected by having the most physicians surveyed (48), compared with Fitzpatrick (37) and Scanlon (39). 19 physicians came from the two most Republican-leaning Pennsylvania House Districts.

F. Interpretation of Data

The data we obtained are imprecise, because they are primarily based on the recall (of up to four years) of busy physicians, each of whom deal with dozens of patients. Small differences over time or between districts may well be the result of poor recall or biases due to survey design. Nevertheless, significant differences are probably reliable and based on identifiable trends.

II. COVID Vaccine Uptake

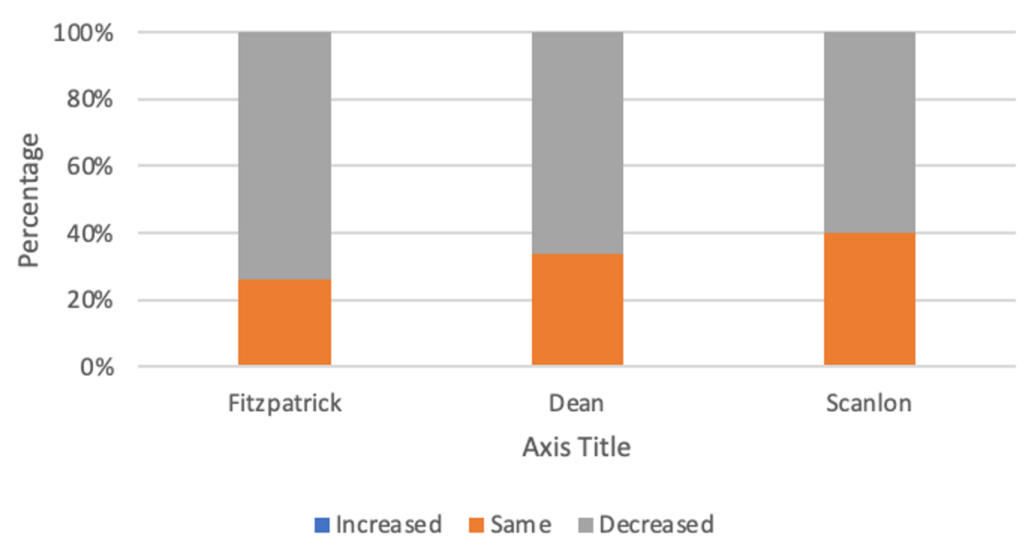

As expected, most physicians reported very high initial uptake of the COVID vaccine among all groups, especially adults. Figure 1 represents the number of responses (Y axis) against time (2021 or 2023) and vaccine-recipient type (adult, child, infant). As the chart demonstrates, most physicians reported nearly every adult receiving a vaccine when first offered (a few may have had medical exemptions to vaccinations).

As noted above, when the mRNA COVID vaccines were first rolled out in late 2020 and early 2021, they were touted as more than 90% effective and that they would (or, at least, might) reduce transmission. Vaccines were also required for many jobs and for travel, etc. By late 2023, when the latest booster was made available, fewer adults were taking it, as well as far fewer children and almost no infants.

Perhaps this can be explained by a greater appreciation that the vaccines were less effective than originally touted, did not appreciably reduce transmission, were no longer required for jobs or travel, and that the side effects more widely explained. Additionally, the disease itself changed, becoming more contagious, but less deadly (though the long-term trajectory remains indeterminant).[13] By lowering viral loads, vaccines probably lowered transmission, but many vaccinated individuals still got the disease.[14] Many patients may also regard the side effects of vaccination—such as a sore arm and the possibility of feeling bad for a day or two—as not worthwhile, given that the disease itself appears little worse than a bad cold. Several physicians mentioned this as among the plausible reasons for declining uptake.

FIGURE 1: Montgomery County – COVID Vaccine Uptake

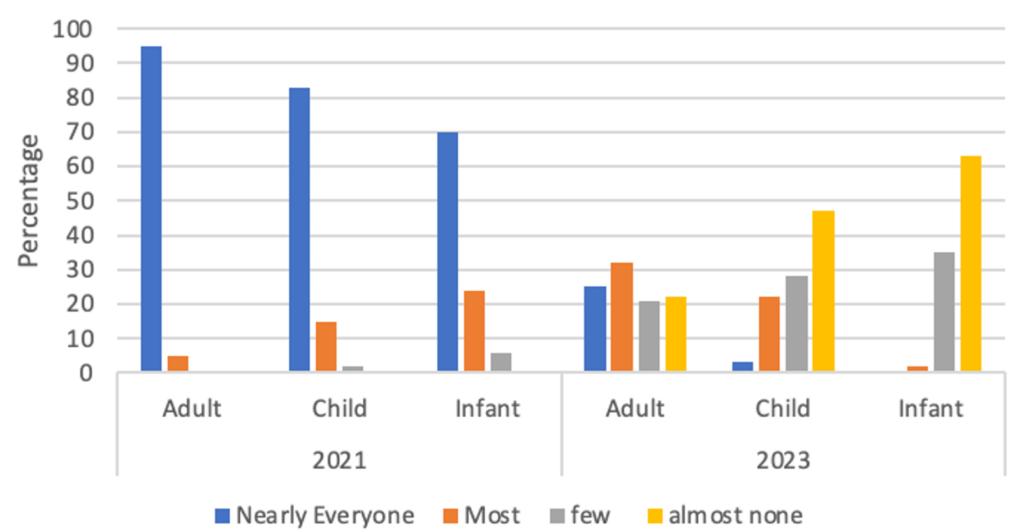

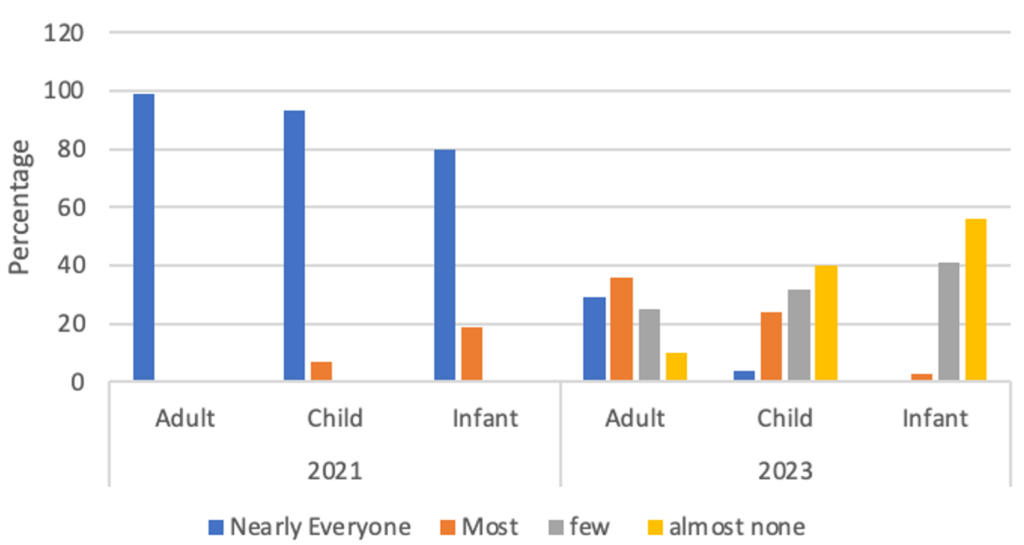

There was very little difference across the three U.S. House districts. While uptake was marginally lower in the Republican Rep. Fitzpatrick’s district, the difference was not statistically significant. In the two most Republican-leaning Pennsylvania House districts, however, there was a notable difference, as can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Initial uptake was not as great in these two districts, and it is almost non-existent for the most recent booster. This is noteworthy, given that Montgomery County follows Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advice that everyone over six months old should receive the latest booster.[15] The vast majority of these districts’ patients are ignoring CDC advice.

FIGURE 2: Montgomery County (12D) Districts – COVID Vaccine Uptake

FIGURE 3: Montgomery County (2R) Districts – COVID Vaccine Uptake

A. Other Vaccines

COVID is one disease among many. Other diseases that require vaccinations obviously have not disappeared. Question 4 sought to gather information about the uptake of these other vaccines over the same period (early 2021 to late 2023). Here, the data are significant, as demonstrated in Figure 4. Not one physician reported an increase in vaccine uptake for these other diseases. While approximately a third reported no change, fully two-thirds (slightly more in the Republican areas) have seen a decrease in vaccination uptake.

This is a very broad measure and far more detailed surveys are required to understand exactly which vaccines are being missed—i.e., whether it is the annual (and not particularly effective) flu vaccines, or the far more important and less-frequent (often a one-off in childhood) vaccines for diseases such as measles, polio, or tuberculosis. The data below also do not show by how much vaccine rates are falling.

FIGURE 4: Non-COVID Vaccine Change in Uptake, 2021-2023

Nevertheless, that rates are falling is potentially worrying and deserving of attention.

III. Vaccine Opinions

The latter questions in the survey refer to opinions about vaccines and, where quantifiable, how they have changed, as well as specific comments made by patients (and the parents of patients) and physicians about vaccines. These responses do not rise much above anecdotes, but they may provide some insight into patient and physician concerns. These comments could also help to design more detailed surveys in the future.

- The vast majority of physicians reported a large decline in support for COVID vaccinations (as reflected in uptake) and a much smaller, but still important, decline in support for all vaccines.

- Most physicians report patient concerns about the safety of COVID (and, increasingly, other) vaccines. Patients are uncertain of, but worried about, social-media reports of vaccine harm. Given that social media was the only place that supported the notion that the SARS-CoV-2 virus originated in a lab—and permitted discussion of other theories and concerns, many of which turned out to be true—it is perhaps not surprising that many patients were inclined to worry about reports of vaccine harm that also appeared on social media. These patients were less likely to take the vaccine themselves, but more likely to take it than to let their children do so. This was especially true among the many patients who referred to the “lies” told by health authorities (Anthony Fauci was named repeatedly). A few patients appeared to be very angry about being mandated to take a potentially unsafe vaccine, even if they had recently had the disease.

- Patients offered more subtle comments—“nuanced” was the word mentioned by more than one physician—about the scientific illiteracy of health authorities who demanded COVID vaccines even for people who had recently had the disease. This led to a “total” distrust of vaccine policy among some patients, which physicians reported has definitely contributed to lowering flu-vaccine uptake, although one physician reported that “it’s too early to tell for other vaccines.” Some physicians agreed with their patients that the advice was unscientific.

- Some physicians also said that their trust in vaccination approval, efficacy, and health authorities’ advice had declined.

A. Discussion

A large NIH survey about vaccination opinions among 737 physicians was undertaken in May 2021, when COVID vaccines were taken in vast numbers.[16] The summary findings were that “10.1% of primary care physicians do not agree that, in general, vaccines are safe, 9.3% do not agree they are effective, and 8.3% do not agree they are important.” Evidently, the vast majority of physicians accepted their safety, efficacy, and importance, but it is both interesting and relevant that a small minority did not. One reason reported was that the pharmaceutical industry is not widely trusted and that some vaccinations, such as for flu, are often not that effective.

To ensure rapid distribution of COVID vaccines, pharmaceutical producers were given (temporary) immunity from liability related to vaccine-induced harm, which probably fueled some additional skepticism (a point physicians said a few patients made when refusing COVID vaccines).[17] This is obviously a tricky area, as the manufacturers might not have agreed to sell the vaccines in the United States without such protections.

By mid-2023, federal vaccine mandates as a requirement for federal jobs and international travel had been removed.[18] It is therefore not that surprising that the uptake of COVID vaccine boosters collapsed among infants and children, and fell markedly amongst adults. One comment made by a few physicians was that uptake was close to zero, as well, for adults under 40, while being nearly universal among adults over 70, or with co-morbidities. This likely demonstrates that those most at-risk were, indeed, reading the scientific situation correctly and taking the vaccine.

It is important not to overinterpret these results. The data could be the result of faulty recollections by busy physicians. Even if entirely accurate, they may reflect a temporary shift, rather than an actual trend in increased vaccine resistance. But these data are worrying if they are sustained and reflective more broadly than in one county in Pennsylvania.

IV. Conclusion

The development of COVID vaccines was a truly remarkable phenomenon. Within one year of the pandemic’s start, pharmaceutical companies had developed multiple vaccines, while the previous record for the fastest vaccine developed (for mumps) took four and half years.[19] These vaccines saved hundreds of thousands of lives, especially among the old and those with comorbidities who were most at risk from severe COVID.

But the vaccines were oversold, were not as effective as first touted, did not fully prevent transmission and, like most vaccines, posed some risks. By making them mandatory for jobs and travel, people who were disinclined to take them appear to have become more hostile to vaccines in general. The exact reasons for the downturn in COVID vaccination are myriad. Some are due to vaccine failings, some to inappropriate political demands, but some are related to the disease changing to a more virulent but less harmful form, making vaccination less attractive.

Further research should establish whether the results in this survey are replicated over time and in larger groups. More importantly, there is a need to establish whether vaccine hesitancy applies across all vaccines or whether it is limited to COVID and seasonal vaccines with weak efficacy (such as influenza).

V. Appendix

Data from most recent U.S. Census and election for Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.[20]

Data for the two Republican-leaning Pennsylvania House districts.[21]

[1] COVID-19 Vaccines, U.S. Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).

[2] Kathy Katella, Comparing the COVID-19 Vaccines: How Are They Different?, Yale Medicine (Oct. 5, 2023), https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-19-vaccine-comparison.

[3] Huong Q. McLean, et al., Interim Estimates of 2022–23 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness — Wisconsin, October 2022–February 2023, Ctr. Disease Control & Prevention (Feb. 24, 2023), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7208a1.htm.

[4] COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States, Ctr. Disease Control & Prevention, https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-people-booster-percent-pop5 (last visited Feb. 16, 2024).

[5] Debunking COVID-19 Myths, Mayo Clinic (Sep. 2, 2021), https://data.cdc.gov/d/rh2h-3yt2/visualization (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).

[6] Colleen Moriarty, The Link Between Myocarditis and COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines, Yale Medicine (Jun. 24, 2021), https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/myocarditis-coronavirus-vaccine.

[7] Anouk Oordt-Speets, et al., Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccination on Transmission: A Systematic Review, MDPI (2023), https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/3/10/103.

[8] Kevin Liptak & Kaitlan Collins, Biden Announces New Vaccine Mandates That Could Cover 100 Million Americans, CNN (Sep. 9, 2021), https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/09/politics/joe-biden-covid-speech/index.html.

[9] Sara Diani, et al., SARS-CoV-2-The Role of Natural Immunity: A Narrative Review, Nat’l Ctr. Biotechnology Info. (Oct. 25, 2022), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36362500/#:~:text=Conclusions%3A%20this%20extensive%20narrative%20review,SARS%2DCoV%2D2%20vaccination.

[10] Vaccines & Immunizations, U.S. Dept. Health & Human Serv., https://www.hhs.gov/vaccines/vaccines-national-strategic-plan/index.html (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).

[11] COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness, Ctr. Disease Control & Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/whats-new/covid-19-vaccine-effectiveness.html (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).

[12] Jonathan Chait, How Vaccine Skeptics Took Over the Republican Party. A Case Study in the Party’s Dysfunction, Intelligencer (Oct. 21, 2022), https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2022/10/how-vaccine-skeptics-took-over-the-republican-party.html; State Government Policies About Vaccine Requirements (Vaccine Passports), 2021-2022, Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/State_government_policies_about_vaccine_requirements_(vaccine_passports),_2021-2022 (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).

[13] Ádám Kun, et al., Do Pathogens Always Evolve to Be Less Virulent? The Virulence–Transmission Trade-Off in Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic, 74 Biol. Futura 69–80 (2023), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42977-023-00159-2.

[14] Anouk Oordt-Speets, et al., Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccination on Transmission: A Systematic Review, 3(10) COVID 1516-1527 (2023), https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/3/10/103.

[15] CDC Recommends Updated COVID-19 Vaccine for Fall/Winter Virus Season, Ctr. Disease Control & Prevention (Sep. 12, 2023), https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/p0912-COVID-19-Vaccine.html.

[16] Timothy Callaghan, et al., Imperfect Messengers? An Analysis of Vaccine Confidence Among Primary Care Physicians, 40(18) Vaccine 2588–2603 (Apr. 20, 2022), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8931689.

[17] Shayna Greene, Fact Check: Are Pharmaceutical Companies Immune From COVID-19 Vaccine Lawsuits?, Newsweek (Jan. 19, 2021), https://www.newsweek.com/fact-check-are-pharmaceutical-companies-immune-covid-19-vaccine-lawsuits-1562793.

[18] The Biden-?Harris Administration Will End COVID-?19 Vaccination Requirements for Federal Employees, Contractors, International Travelers, Head Start Educators, and CMS-Certified Facilities, White House (May 1, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/01/the-biden-administration-will-end-covid-19-vaccination-requirements-for-federal-employees-contractors-international-travelers-head-start-educators-and-cms-certified-facilities.

[19] Dave Roos, How a New Vaccine Was Developed in Record Time in the 1960s, History.com (Oct. 4, 2023), https://www.history.com/news/mumps-vaccine-world-war-ii.

[20] ArcGIS, https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/a560279ebf2844b2ba267d6f50602668/page/US-Congressional/?data_id=dataSource_8-185df68cfdd-layer-4%3A30%2CdataSource_9-185df6f79b7-layer-4%3A62, (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).

[21] ArcGIS, https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/a560279ebf2844b2ba267d6f50602668/page/PA-House/?data_id=dataSource_8-185df68cfdd-layer-4%3A30%2CdataSource_9-185df6f79b7-layer-4%3A62, (last visited Feb. 15, 2024).