Title II: The Model T of Broadband Regulation

The Federal Communications Commission’s (“FCC”) recent order to reclassify broadband internet access as a Title II “telecommunications service” under the Communications Act, will subject the industry to extensive public utility style regulation. While “net neutrality” principles drove were the initial justifications for Title II, the FCC’s current rationale has shifted to national security, public safety, and privacy concerns and broader regulatory control. Title II’s comprehensive regulatory framework threatens to commoditize broadband by banning practices like paid prioritization, zero-rating, and usage-based pricing, thereby reducing consumer choice and stifling innovation. Such heavy-handed regulation is unnecessary given the increasing competition in broadband markets from new technologies like 5G and satellite internet. Title II common carrier regulation is an outdated regulatory model ill-suited for modern broadband services and may do more harm than good for consumers.

I. Introduction

Net neutrality is the idea that internet service providers (“ISPs”) should treat all data transmitted over the internet the same, and should not discriminate among consumers, entities that provide content, or applications that use the internet. Whether net neutrality should be mandated by rules and regulations — such as the Federal Communications Commission’s (“FCC”) latest net-neutrality regulations — has been a highly controversial topic since the early 2000s. The FCC has imposed net-neutrality rules twice before, in 2010 and 2015, only to see them struck down by courts or repealed, as the commission’s partisan makeup changed. Last month, in a party line vote, the Commission voted to regulate broadband internet under Title II of the Communications Act and impose net-neutrality rules.[1]

For much of the internet’s history, broadband telecommunications have been regulated as an “information service” under Title I of the Communications Act, which is widely considered to be a relatively light-touch regulatory framework. Since the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order, the agency has attempted to reclassify broadband as a “telecommunications service” under Title II, subject to the more heavy-handed regulation imposed on public utilities and “common carriers.” Under Title II, broadband companies are required to provide service to all customers equally and may be subject to public-utility-style regulation, including price controls, certificates of convenience and necessity, and quality-of-service requirements.

Because regulation under Title II entails much more than just net neutrality, critics complain that reclassifying broadband providers as common carriers amounts essentially to a federal takeover of a large part of the U.S. economy, used by nearly every American every day. On the other hand, proponents claim that precisely because broadband is so important to the economy, and even to the functioning of society, it must be managed by a government agency that will ensure equal access, maintain privacy and free speech, and protect national security and public safety.

While net neutrality is just a small piece of Title II, Title II is just one cog in massive gearwork of new federal regulations affecting nearly every aspect of access and use of the internet. Under rules adopted by the FCC, broadband deployment, upgrades, pricing, promotions, quality of service, and even marketing and advertising are now subject to FCC monitoring, scrutiny, and enforcement.

In this article, we provide a brief historical overview of net neutrality, including the debates over whether internet service is best classified as a Title I information service or at Title II telecommunications service, and how understanding of the underlying concerns has changed over the past 25 years. We then take a deeper look at what Title II regulation involves, to understand whether it is suitable to address contemporary concerns. We conclude by examining Title II within a broad regulatory framework that is — intentionally or unintentionally — banning or hindering many of the dimensions across which broadband providers compete. Some may argue that the commodification of broadband will nudge broadband toward a more competitive market with standardized (or near-standardized) products. In the process, however, consumers will see dwindling options among service offerings much like Henry Ford’s quip that consumers could get a Model T in any color they like, so long as it’s black.

II. Is Net Neutrality Still a Thing?

Columbia Law School Professor Tim Wu is credited with articulating the concept of “net neutrality” as an anti-discrimination framework, “to give users the right to use non-harmful network attachments or applications, and give innovators the corresponding freedom to supply them.”[2] In a letter to the FCC, Wu & Lawrence Lessing drew a comparison to electric utilities which, as common carriers, provide electricity to all paying customers “without preference for certain brands or products.”[3] Indeed, Wu argued that his net neutrality proposal was “similar” to historic common carriage requirements.[4]

In the years since Wu introduced the term, net-neutrality policies have focused on the prohibition of three practices:

- Blocking of legal content, such as when a phone company providing service was accused of blocking Voice over Internet Protocol (“VoIP”) telephone service that competed with the phone company’s landline business.[5]

- Throttling, or the intentional slowing of an internet service, such as when an ISP was alleged to have slowed or interfered with file sharing using BitTorrent protocols;[6] and

- Paid prioritization, in which a content provider pays an ISP a fee for faster service — commonly referred to as “fast lanes.”[7]

In 2004, FCC Chair Michael Powell articulated four “Internet Freedoms,” derived from Wu & Lessig’s work.[8] These were subsequently incorporated into the FCC’s 2005 “Internet Policy Statement.”[9]

By this point, the question of Title I versus Title II classification had become a central fracture point in discussions of net neutrality. On its face, Title I offers the FCC little, if any, substantive regulatory authority — indeed, it was created to differentiate unregulated services ancillary to the core telephone network services that the FCC regulated throughout the 20th century. Conversely, Title II provides the FCC with pervasive regulatory authority over the traditional telephone network, from pricing decisions to decisions over what services to offer and even what furniture to buy for meeting rooms.[10] Starting in the late 1990s, the FCC argued that internet service was best treated under Title I. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals subsequently determined that internet service was better understood as a Title II service. The FCC disagreed and, in Brand X the Supreme Court held that the FCC’s determination takes precedence over that of the federal courts.

Thus, understanding of how internet services would be classified went from Title I, to Title II, and back to Title I over a period of seven years: The battle for classification had begun. That continued in the 2010 and 2015 Orders (in which the FCC relied on Title I and then Title II, respectively).

In 2010, the agency issued its Preserving the Open Internet Order, prohibiting blocking and unreasonable discrimination as well as mandating providers disclose the network management practices, performance characteristics, and terms and conditions of their broadband services.[11] In separate 2010 and 2014 cases, The DC Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the 2010 Order’s net neutrality requirements.[12] The courts noted that, because broadband providers were regulated under Title I as information services, they were not common carriers and could not be subject to net neutrality’s common carriage rules. A little more than a year after the court’s 2014 decision, in 2015, the FCC adopted the Open Internet Order, that reclassified broadband internet as a Title II common carrier telecommunication service and adopted new net neutrality rules prohibiting blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization.[13] The order also imposed a “general conduct” rule that prohibited broadband providers from “unreasonably interfer[ing] or unreasonably disadvantag[ing]” users from accessing the content or services of their choice.

In 2017, the FCC reversed course and repealed the 2015 Order with its Restoring Internet Freedom Order.[14] The order (again) reclassified broadband as a Title I information service, thereby eliminating net neutrality and general conduct rules. The order also preempted any state or local laws “that would effectively impose rules or requirements that [the FCC] repealed or decided to refrain from imposing,” or that would impose “more stringent requirements for any aspect of broadband service” addressed by the 2017 Order. In 2019, an appeals court upheld much of the order, but vacated the order’s preemption of state and local laws.[15]

Until recently, much of the debate was over whether net neutrality was necessary and how it would affect continued investment by ISPs’ in their networks. Advocates for federal intervention claimed it was necessary for the FCC to preserve or foster the “open internet” by mandating net neutrality. Opponents countered that such intervention was (1) unnecessary because providers were not engaging in widespread practices contrary to net neutrality, and (2) harmful because the prohibitions were so tight that they would stifle investment and innovation in new business models.

Something happened along the way from then to now: No one seems to care much about net neutrality anymore.[16] One reason is because most people are happy with their internet service. Since 2021, more households are connected to the internet, broadband speeds have increased while prices have declined, more households are served by more than a single provider, and new technologies — such as satellite and 5G — have expanded internet access and intermodal competition among providers.[17] Another reason is a shift in perception of who is blocking or throttling content. Much of that ire has turned towards websites, apps, and device providers.[18] Much of the public no longer sees broadband providers as the bogeymen.

The FCC itself seems to have downgraded “net neutrality” as a justification for heavy handed Title II regulation in favor of other reasons. For example, “national security” was mentioned only three times in the 2015 Order, but 181 times in the 2024 Order. The 2015 Order makes no mention of China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, or “data security;” in the 2024 Order China is mentioned 140 times and “data security” 15 times. Cybersecurity got a single mention in the 2015 Order, but 73 in the 2024 Order. This is a pretty clear indication that the FCC intends to do much more with its expansive Title II powers than merely prevent blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization.

III. Title II Is Much More than Net Neutrality

Net neutrality is often used as the hook for regulating broadband providers as common carriers. But Title II is an expansive provision in the Communications Act. Among its many provisions, Title II allows federal rate regulation of broadband, as well as Section 214 “certificate of convenience and necessity” regulations requiring providers to obtain the FCC’s approval before constructing new networks, offering new services, discontinuing outdated offerings, or transferring control of licenses. The Commission’s order forbears rate regulation and grants “blanket” Section 214 authority to all current broadband providers, with the exception of five Chinese providers.

The 2024 Order’s “general conduct standard” provides the FCC with unlimited discretion to intervene in innovative business models. The order states the general conduct standard “prohibits unreasonable interference or unreasonable disadvantage to consumers or edge providers” that serves as a “catch-all backstop” to allow the FCC to intervene when it finds that an ISP’s conduct could harm consumers or content providers.

The FCC has a history of invoking the general conduct standard to scrutinize two common practices:

- Zero-rating; and

- So-called “data caps” and usage-based pricing.

Zero-rating is the practice of excluding certain online content or applications from a subscriber’s allowed data usage. For example, when AT&T owned HBO, it exempted HBO Max content from AT&T users’ data allowance.

Zero-rating can make some popular services more accessible and affordable for lower-income users, who may have limited data plans. Zero-rating also allows ISPs to offer value-added services and to differentiate their offerings, spurring competition and innovation in the broadband market.

In December 2016, the FCC sent letters to both AT&T and Verizon Communications, warning their zero-rating programs could harm competition and consumers.[19] In the last days of the Obama administration, the FCC released a staff review of sponsored data and zero-rating practices in the mobile-broadband market concluding such practices “may harm consumers and competition… by unreasonably discriminating in favor of select downstream providers.”[20] Less than a month later, in the early days of the Trump administration, the FCC retracted the report.[21]

We can expect that under the 2024 Order — identical in most ways to the 2015 Order under which these practices were investigated — the Commission will once again use its powers to scrutinize zero-rating practices with an eye toward prohibiting them. Indeed, the 2024 Order characterizes, “sponsored-data programs as the type of practices that may raise concerns under the general conduct standard” that will be subject to a “case-by-case review.”

Usage-based pricing can be thought of as a “pay-as-you-go” plan in which consumers pay in advance for a certain amount of data per month. If they exceed that amount (what some would call a “cap”), then the consumer has the option to purchase more data. Some consumer groups claim that data caps and usage-based pricing are little more than a “money grab” by providers who derive additional revenue from overage charges or by upgrading users to a tier with a larger data allowance.[22] On the other hand, providers say that usage-based pricing is no different from nearly every other consumer product in which consumers pay for what they use. They argue that, without usage-based pricing, modest users of data would subsidize those who use copious amounts of data.[23]

In June 2023, FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel announced that she would ask her fellow commissioners to support a formal notice of inquiry to learn more about how broadband providers use data caps on consumer plans.[24] That same day, the FCC launched a “Data Caps Stories Portal” for “consumers to share how data caps affect them.” The 2024 Order indicates “providers can implement data caps in ways that harm consumers or the open Internet” and the FCC will “evaluate individual data cap practices under the general conduct standard.”

If, however, sponsored-data, zero-rating, data caps, and usage-based pricing practices harm competition or consumers, these concerns can be addressed with a straightforward application of existing antitrust and consumer-protection laws. Antitrust enforcers and courts assess such practices under the rule of reason — an approach that avoids a presumptive condemnation because they only rarely result in actual anticompetitive harm. Under a rule-of-reason approach, the effects of potentially harmful conduct are typically evaluated and weighed against the various aims that competition law seeks to promote. Only following that review is it determined whether particular conduct is harmful and, if so, whether there are procompetitive benefits that outweigh the harm.

Consumer protection is the purview of the Federal Trade Commission. Section 5 of the FTC Act prohibits “unfair methods of competition in or affecting commerce, and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.” The FTC has a long history of using its authority, such as recent actions to protect the privacy of consumers’ health records.[25] But, the FTC has no Section 5 authority over “common carriers subject to the Acts to regulate commerce,” which includes, according to the FTC Act, the “Communications Act of 1934 and all Acts amendatory thereof and supplementary thereto.” Thus, by classifying broadband providers as Title II common carriers, the FCC has stripped the FTC of its authority to protect consumers using Section 5.

IV. Commoditizing Broadband and the Elusive Search for Perfect Competition

In its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, the Commission argued that broadband internet access services are “[n]ot unlike other essential utilities, such as electricity and water” and that high-speed internet “was essential or important to 90 percent of U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.”[26] The Commission argues that broadband internet is therefore an essential public utility and should be regulated as such.

But many essentials to human survival — shelter, food, clothing — are not subject to common-carrier regulations, because they are provided by multiple suppliers in competitive markets. Utilities are considered distinct because they tend to have such significant economies of scale that (1) a single monopoly provider can provide the goods or services at a lower cost than multiple competing firms, and/or (2) market demand is insufficient to support more than a single supplier.[27] Water, sewer, electricity distribution, and natural gas are typically considered “natural” monopolies under this definition.[28] In many cases, not only are these industries treated as monopolies, but their monopoly status is codified by laws forbidding competition. At one time, local and long-distance telephone services were considered — and treated as — natural monopolies, as was cable television.[29]

Over time, innovations have eroded the “natural” monopolies in telephone and cable.[30] In 2000, 94 percent of U.S. households had a landline telephone, and only 42 percent had a mobile phone.[31] By 2018, those numbers flipped.[32] In 2015, 73 percent of households subscribed to cable or satellite-television services.[33] Today, fewer than half of U.S. households subscribe.[34] Much of that transition is due to the enormous improvements in broadband speed, reliability, and affordability. Similarly, entry and intermodal competition from 5G, fixed wireless, and satellite has meant that more than 94 percent of the country can now access highspeed broadband from three or more providers, thereby eroding the already tenuous claims that broadband-internet service is akin to a utility.

Much of the FCC’s motivation in its recent regulatory push — Title II, digital discrimination, and broadband “nutrition labels” — seems to be driven by a misplaced notion of perfect competition, as described in introductory economics textbooks. Under perfect competition, prices paid by consumers equal the marginal cost of production, that cost is the minimum average cost, and firms earn zero economic profits. Perfect competition is too perfect. While perfection can be sought, it can never be achieved in the real world because the real world is a messy place.

Perhaps the messiest assumption of perfect competition is that each firm produces undifferentiated commodity products.[35] Broadband internet service is not a commodity. Providers use different technologies (e.g. fiber, 5G, copper wire) with different performance characteristics (e.g. speed and latency). Providers offer different service agreements. Some have early termination fees, while others don’t; some have “all-you-can-eat” data usage, while other have usage-based billing; some may have zero-rating while other don’t. With so much variation in services both across and within providers, some have argued that most consumers are not well-informed — if not confused — about their broadband options.

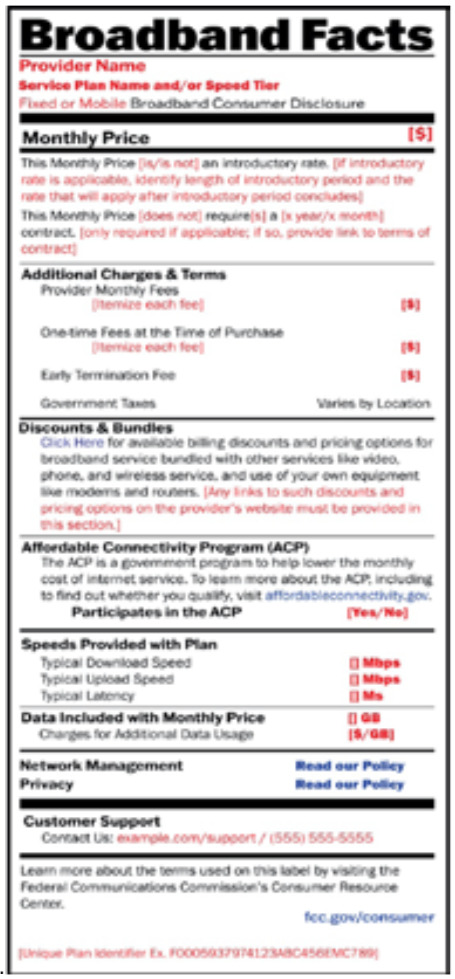

As a first step to commoditizing broadband, at the direction of the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure bill, the FCC adopted its broadband “nutrition label” rules.[36] Providers must display a nutrition label for each plan it offers. Consumers can then use the labels as an “apples to apples” comparison across plans and providers. Despite the cost to produce the labels, the uncertainty whether consumers will find the labels useful, and whether the full force of the federal government is necessary to display the labels, it’s difficult to argue that consumers are worse off by having easy-to-use information readily available.

With the FCC’s recent digital discrimination rules, the agency took another step toward commoditizing broadband. The infrastructure act required the Commission to adopt final rules “preventing digital discrimination of access based on income level, race, ethnicity, color, religion, or national origin.”[37] The FCC could have issued a narrow rule to outlaw intentional discrimination by broadband providers in deployment decisions, in a way that would treat a person or group of persons less favorably than others because of a listed protected trait. This rule would be workable, leaving the FCC to focus its attention on cases where broadband providers fail to invest in deploying networks due to animus against those groups.

Instead, the FCC’s final order creates an expansive regulatory scheme that gives it essentially unlimited discretion over anything that would affect the adoption of broadband. It did this by adopting a differential impact standard that applies not only to broadband providers, but to anyone that could “otherwise affect consumer access to broadband internet access service.”[38] The order spans nearly every aspect of broadband deployment, including, but not limited to network infrastructure deployment, network reliability, network upgrades, and network maintenance. In addition, the order covers a wide range of policies and practices that while not directly related to deployment, affect the profitability of deployment investments, such as pricing, discounts, credit checks, marketing or advertising, service suspension, and account termination. Most troubling, the order considers price among the “comparable terms and conditions” subject to its digital discrimination rules.[39] Taken together, with these rules, the FCC gave itself nearly unlimited authority over broadband providers, and even a great deal of authority over other entities that can affect broadband access, including other federal agencies, state and local governments, nonprofit organizations, and apartment owners.

Because the infrastructure act included income level as a protected trait, the FCC opened a Pandora’s Box in which nearly any organization’s policies and practices can be scrutinized as discriminatory.[40] For example many providers offer plans explicitly targeted at low-income consumers, such as Xfinity’s Internet Essentials program.[41] These programs are at risk of scrutiny under the digital discrimination rules. Moreover, the rules will likely stifle new deployment or upgrades out of fear of alleged disparate effects. If they don’t upgrade everyone, they could be accused of discrimination. At the extreme, providers will be faced with the choice to upgrade everyone or upgrade no one. Because they cannot afford to upgrade everyone, then they will upgrade no one.

While unintentional, the digital discrimination rules are another step toward commoditization. Providers must offer comparable speeds, capacities, latency, and other quality of service metrics in a given area, for comparable terms and conditions, including price, thereby erasing many of the dimensions across which providers compete.

Lastly under Title II and its net neutrality provisions, the FCC is erasing more competitive dimensions. Banning paid prioritization forces all data to be treated equally, even if customers or services would benefit from differentiated offerings. Without flexibility in how services are delivered and priced, companies lose incentives to develop better networks and new innovations for specific use cases like high-bandwidth video streaming or remote medical services. A ban on data throttling removes essential network-management tools that could prevent congestion and improve overall customer experience. If — as expected — the FCC moves to ban zero-rating and usage-based billing, consumers will have even fewer choices among broadband internet services. In the extreme, providers will simply be providing “dumb pipes” with standardized service. While such efforts may mimic perfect competition’s commodity condition, it’s not clear that consumers will benefit from one-size-fits-all broadband.

V. Conclusion

As we have recounted above, discussion about net neutrality concerns grew out of the era in which telecommunications services were provided by regulated, natural, monopoly carriers. In that era, there was legitimate need for pervasive regulation of these carriers. But these discussions also started concurrent with changing competitive dynamics in these markets. This historical context centered net neutrality in debates over the ongoing basis for the FCC’s own authority: Whether the regulatory structure of Title II, long central to the FCC’s mission, is still fit to task in contemporary markets. Looking at the comprehensive regulatory framework contemplated by Title II, the answer is clear: Regulation is driving internet services toward increasingly commodity services, reducing consumer choice in the process. Much like the Model T, Title II may have been necessary in the past, but it is now an artifact of a bygone era and should be allowed to slip into history.

[1] Declaratory Ruling, Order, Report and Order, and Order on Reconsideration, In the Matter of Safeguarding and Securing the Open Internet; Restoring Internet Freedom, WC Docket No. 23-320, WC Docket No. 17-108 (Apr. 25, 2024) [hereinafter “2024 Order”].

[2] Tim Wu, Network Neutrality, Broadband Discrimination, 2 J. Telecomm. & High Tech. L. 141, 142 (2003) [emphasis in original].

[3] Tim Wu & Lawrence Lessig, Ex Parte Submission, Appropriate Regulatory Treatment for Broadband Access to the Internet Over Cable Facilities, CS Docket No. 02-52 (Aug. 22, 2003), available at https://web.archive.org/web/20041204012743/http://faculty.virginia.edu/timwu/wu_lessig_fcc.pdf (“When consumers buy a new toaster made by General Electric they need not worry that it won’t work because the utility company makes a competing product.”).

[4] Wu, supra note 2 at 150.

[5] Lawrence Lessig, Voice-Over-IP’s Unlikely Hero, Wired (May 1, 2005), https://www.wired.com/2005/05/voice-over-ips-unlikely-hero.

[6] Declan McCullagh, FCC Formally Rules Comcast’s Throttling of Bittorrent Was Illegal, CNet (Aug. 20, 2008), https://www.cnet.com/tech/tech-industry/fcc-formally-rules-comcasts-throttling-of-bittorrent-was-illegal.

[7] Chao Liu & Cooper Quintin, Internet Service Providers Plan to Subvert Net Neutrality. Don’t Let Them, Elec. Frontier Found. (Apr. 19, 2024), https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2024/04/internet-service-providers-plan-subvert-net-neutrality-dont-let-them.

[8] Michael Powell, Preserving Internet Freedom: Guiding Principles for the Industry, 3 J. Telecomm. & High Tech. L. 5 (2004).

[9] Appropriate Framework for Broadband Access to the Internet over Wireline Facilities, 20 FCC Rcd. 14,986, 14,987-88 (2005).

[10] 47 CFR § 32.2000.

[11] Report and Order, In the Matter of Preserving the Open Internet; Broadband Industry Practices, GN Docket No. 09-191, WC Docket No. 07-52 (Dec. 21, 2010) [hereinafter “2010 Order”].

[12] For a more thorough summary, see Chris D. Linebaugh, Cong. Research Serv. LSB10693, ACA Connects v. Bonta: Ninth Circuit Upholds California’s Net Neutrality Law in Preemption Challenge (Feb. 2, 2022), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/LSB/LSB10693.

[13] Report and Order on Remand, Declaratory Ruling, and Order, In the Matter of Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet, GN Docket No. 14-28 (Mar. 15, 2015) [hereinafter “2015 Order”].

[14] Declaratory Ruling, Report and Order, and Order, In the Matter of Restoring Internet Freedom, WC Docket No. 17-108 (Dec. 14, 2017) [hereinafter “2017 Order”].

[15] Mozilla Corp. v. FCC, 940 F.3d 1 (D.C. Cir., 2019)

[16] See, e.g. FCC reinstates net neutrality policies after 6 years, NPR Weekend Edition Saturday (May 4, 2024), available at https://www.npr.org/2024/05/04/1249166941/fcc-reinstates-net-neutrality-policies-after-6-years (noting that “Net neutrality was once the biggest controversy about the internet . . . .” and concluding “I think that net neutrality may be one of the most overhyped regulations on both sides.”).

[17] Eric Fruits, Ben Sperry, & Kristian Stout, ICLE Comments to FCC on Title II NPRM, Int’l Ctr. for L & Econ. (Dec. 14, 2023), https://laweconcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ICLE-Comments-on-2023-FCC-Title-II-NPRM.pdf\.

[18] See, for example, Oral Dissent of Brendan Carr, In the Matter of Safeguarding and Securing the Open Internet; Restoring Internet Freedom, WC Docket No. 23-320, WC Docket No. 17-108 (Apr. 25, 2024), https://youtu.be/W0CFV9DNSLU?si=dmS4MAnSvnEu-P-J (“After 2017 it wasn’t the ISPs that abuse their positions in the internet ecosystem. It was not the ISPs that blocked links to the New York Post’s Hunter Biden laptop story. Twitter did that. It wasn’t the ISPs that just one day after lobbying this FCC on this order, blocked all posts from a newspaper and removed the links to the outlet after it published a critical article. Facebook did that. It wasn’t the ISPs that earlier this month blocked links to a California-based news organization from showing up in search results to protest a state law. Google did that. It wasn’t the ISPs that blocked Beeper Mini, an app that allowed interoperability between iOS and messaging. Apple did that. Since 2017, we have learned that the real abusers of gatekeeper power were not ISPs operating at the physical layer, but big tech companies at the applications layer.”).

[19] Thomas Gryta, FCC Raises Fresh Concerns Over “Zero-Rating” by AT&T, Verizon, Wall St. J. (Dec. 2, 2016), https://www.wsj.com/articles/fcc-raises-fresh-concerns-over-zero-rating-by-at-t-verizon-1480695463.

[20] Policy Review of Mobile Broadband Operators’ Sponsored Data Offerings for Zero-Rated Content and Services (Jan. 11, 2017), https://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2017/db0111/DOC-342987A1.pdf.

[21] Order, In the Matter of Wireless Telecommunications Bureau Report: Policy Review of Mobile Broadband Operators’ Sponsored Data Offerings for Zero Rated Content and Services (Feb. 3, 2017), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-17-127A1.pdf.

[22] Jon Brodkin, Comcast Disabled Throttling System, Proving Data Cap Is Just a Money Grab, Ars Technica (Jun. 13, 2018), https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2018/06/comcast-says-it-doesnt-throttle-heaviest-internet-users-anymore.

[23] Brian C. Albrecht & Jonathan W. Williams, Net Neutrality Is an Idea That Should Have Stayed Dead, Boston Globe (May 6, 2024), https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/05/06/opinion/net-neutrality-data-caps. See also, Eric Fruits, The Curious Case of the Missing Data Caps Investigation, Truth on the Market (Feb. 5, 2024), https://truthonthemarket.com/2024/02/05/the-curious-case-of-the-missing-data-caps-investigation.

[24] Chairwoman Rosenworcel Proposes to Investigate How Data Caps Affect Consumers and Competition (Jun. 15, 2023), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-394416A1.pdf.

[25] Elisa Jillson, Protecting the Privacy of Health Information: A Baker’s Dozen Takeaways from FTC Cases (Jul. 25, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/blog/2023/07/protecting-privacy-health-information-bakers-dozen-takeaways-ftc-cases.

[26] Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, In the Matter of Safeguarding and Securing the Open Internet, WC Docket No. 23-320 (Sep. 28, 2023), available at https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-397309A1.pdf.

[27] See Paul Krugman & Robin Wells, Economics 389 (4th ed. 2015) (“So the natural monopolist has increasing returns to scale over the entire range of output for which any firm would want to remain in the industry—the range of output at which the firm would at least break even in the long run. The source of this condition is large fixed costs: when large fixed costs are required to operate, a given quantity of output is produced at lower average total cost by one large firm than by two or more smaller firms.”).

[28] Id. (“The most visible natural monopolies in the modern economy are local utilities—water, gas, and sometimes electricity. As we’ll see, natural monopolies pose a special challenge to public policy.”).

[29] See Richard H. K. Vietor, Contrived Competition 167 (1994) (“[I]n the early part of the twentieth century, American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) set itself the goal of providing universal telephone services through an end-to-end national monopoly. … By [the 1960s], however, the distortions of regulatory cross-subsidy had diverged too far from the economics of technological change.”); see also Thomas W. Hazlett, Cable TV Franchises as Barriers to Video Competition, 2 Va. J.L. & Tech. 1, 1 (2007) (“Traditionally, municipal cable TV franchises were advanced as consumer protection to counter “natural monopoly” video providers. … Now, marketplace changes render even this weak traditional case moot. … [V]ideo rivalry has proven viable, with inter-modal competition from satellite TV and local exchange carriers (LECs) offering “triple play” services.”).

[30] See id. at 59-73.

[31] Share of United States Households Using Specific Technologies, Our World in Data (n.d.), https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/technology-adoption-by-households-in-the-united-states.

[32] Id. (showing household usage of landlines and mobile phones in 2018 at 42.7 and 95 percent, respectively).

[33] Edward Carlson, Cutting the Cord: NTIA Data Show Shift to Streaming Video as Consumers Drop Pay-TV, NTIA (2019), https://www.ntia.gov/blog/2019/cutting-cord-ntia-data-show-shift-streaming-video-consumers-drop-pay-tv.

[34] Karl Bode, A New Low: Just 46% of U.S. Households Subscribe to Traditional Cable TV, TechDirt (Sep. 18, 2023), https://www.techdirt.com/2023/09/18/a-new-low-just-46-of-u-s-households-subscribe-to-traditional-cable-tv. See also, Shira Ovide, Cable TV Is the New Landline, N.Y. Times (Jan. 6, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/06/technology/cable-tv.html.

[35] Krugman & Wells, supra note 28 at 360 (“A perfectly competitive industry must produce a standardized product.”), 359 (“a standardized product, which is a product that consumers regard as the same good even when it comes from different producers, sometimes known as a commodity”) [emphasis in original].

[36] Order, In the Matter of Empowering Broadband Consumers Through Transparency, CG Docket No. 22-2 (Jul. 18, 2023), available at https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-23-617A1.pdf.

[37] Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 60506(b)(1), 135 Stat. 429, 1246.

[38] See 47 CFR §16.2 (definition of “Covered entity” and “Covered elements of service”).

[39] Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, In the Matter of Implementing the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act: Prevention and Elimination of Digital Discrimination, GN Docket No. 22-69 (Oct. 25, 2023), available at https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-397997A1.pdf (“Indeed, pricing is often the most important term that consumers consider when purchasing goods and services… this is no less true with respect to broadband internet access ser-vices.”).

[40] Eric Fruits, Everyone Discriminates Under the FCC’s Proposed New Rules, Truth on the Market (Oct. 30, 2023), https://truthonthemarket.com/2023/10/30/everyone-discriminates-under-the-fccs-proposed-new-rules.

[41] Internet Essentials, (2024), https://www.xfinity.com/learn/internet-service/internet-essentials.