ICLE Comments to the Brazilian Ministry of Finance on Competition in Digital Markets

Executive Summary

We are thankful for the opportunity to submit comments to the secretariat of economic reforms of the Ministry of Finance’s Public Consultation regarding competition in digital markets. The International Center for Law & Economics (“ICLE”) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan global research and policy center founded with the goal of building the intellectual foundations for sensible, economically grounded policy. ICLE promotes the use of law & economics methodologies to inform public-policy debates and has longstanding expertise in the evaluation of competition law and policy. ICLE’s interest is to ensure that competition law remains grounded in clear rules, established precedent, a record of evidence, and sound economic analysis.

Our comments respectfully suggest careful consideration before approving any sectoral regulation of digital markets in Brazil.

Digital markets are generally dynamic, competitive, and beneficial to consumers. Those benefits derive from increased productivity and relatively cheap access to information. Whereas there are always possible competition issues and anticompetitive behavior, these are neither pervasive nor sufficiently unique to justify strict, sui generis preemptive rules. Instead, existing antitrust laws (Act No. 12,529/2011) are sufficient to address potential anticompetitive practices in digital markets. Furthermore, and as demonstrated by recent case law, the Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica (CADE)—the Brazilian competition authority—has the necessary expertise to handle these cases.

There are, of course, challenges in applying antitrust laws to digital markets. For example, defining relevant markets and dominant positions in multisided platform cases, and in the fast-changing digital landscape, can be difficult. The contours of the relevant market are not always clear, and the boundaries between the digital and nondigital world are sometimes overstated. Those challenges can, however, be properly addressed through the existing legal framework and with some institutional measures, such as equipping CADE with more resources to incorporate advanced, state-of-the-art technical expertise.

Finally, ex-ante regulations like the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) can have unintended consequences, such as stifling innovation, reducing consumer welfare, and increasing compliance costs. They can also lead to increased risks of regulatory capture and rent seeking, as the verdict on whether a gatekeeper has complied with the law often comes down to the degree to which rivals are satisfied. Of course, rivals have a clear personal stake in never being satisfied. By tethering intervention to a comparatively clear public-benefit standard—consumer welfare—competition laws minimize the potential for error costs and decrease the chances that the law will be coopted for private gain.

I. Objectives and Regulatory Rationale

1.1 What economic and competitive reasons would justify the regulation of digital platforms in Brazil?

In general terms, we believe Brazil does not need sectoral regulations for digital platforms, given that the markets for such services are reasonably competitive. According to economic theory and long-tested economic principles, ex-ante regulation[1] is justified only in the presence of market failures[2]. Digital markets, however, do not present the kind of market failures that warrant ex-ante regulation. For example, digital markets do not present natural monopolies, significant externalities, public goods, or informational asymmetries.

To be sure, one can find some levels of informational asymmetries or externalities, but not to such a magnitude that they could not be addressed through market competition (actual or potential) or through general rules, such as data-protection or consumer-protection laws. A more plausible argument can be made regarding the presence of “network effects” in online platforms. If a firm moves fast and is the first to attract customers, that customer base will, in turn, attract more customers and sellers. This network growth could, so the story goes, result in a single firm monopolizing the market. However, as Evans and Schmalensee, have pointed out, that result is far from inevitable:

Systematic research on online platforms by several authors, including one of us, shows considerable churn in leadership for online platforms over periods shorter than a decade. Then there is the collection of dead or withered platforms that dot this sector, including Blackberry and Windows in smartphone operating systems, AOL in messaging, Orkut in social networking, and Yahoo in mass online media.[3]

Some regulations and proposals—namely, the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) or the proposed American Innovation and Choice Online Act (AICOA) in the United States—mention the alleged failures of antitrust law (i.e., “too slow” and “too hard for plaintiffs”) as the primary rationale to regulate digital markets. As Giuseppe Colangelo has explained:

Against this background, the regulatory approaches recently advanced do not seem to reflect the distinctive features of digital markets, but rather the need to design enforcement short-cuts to cope with growing concerns that antitrust law is unable to address potential anticompetitive practices by large online platforms. Hence, in most of the mentioned reports, the revival of regulation seems supported more by an alleged antitrust enforcement failure rather than true a market failure. The goal is indeed to fill alleged enforcement gaps in the current antitrust rules by introducing tools aimed at lowering legal standards and evidentiary burdens in order to address anti-competitive practices that standard antitrust analysis would struggle to tackle.[4]

This could be a plausible justification for regulation. Antitrust cases could be more expedited. Competition agencies and courts should generally have more resources and faster procedures to adjudicate cases before market structures or markets in general change, rendering any potential intervention useless.

The fact that cases are “hard to win”, however, is not a valid justification. This might actually be an advantage, not a shortcoming, of antitrust law—especially in the context of “abuse of dominance” or monopolization cases[5]. Regulations like the DMA replace the concepts of “relevant markets” and “market power” or “dominant position” with others like “core platforms services” or “gatekeeper”, with the express intent of providing shortcuts to condemn business models and practices. But these “shortcuts” have a cost: they can easily lead to condemnation of business models and practices that provide benefits for consumers, such as lower prices and a safer user experience, among others.

Even those open to considering digital-markets regulation acknowledge that there are considerable challenges, especially if the intent is to regulate digital platforms like “essential facilities”:

In the tech industry, the first challenge is to identify a stable essential facility. It must be stable because divestitures take a while to perform, and the cost of implementing them would not be worth its while if the location of the essential facility kept migrating. This condition may not be met, though. While the technology and market segments of electricity, railroads and (up to the 1980s) telecoms had not changed much since the early 20th century, digital markets are fast? moving. This makes it difficult for regulators to identify, collect data on, and regulate essential facilities, if the corresponding technologies and demands keep morphing.[6]

Moreover, even if warranted, regulations create barriers to entry and regulatory risks, and they restrict the monetization of business assets. They also tend to make markets less attractive and could deter potential competitors from entering them. It is possible that the DMA is already producing such consequences. As Alba Ribera has explained:

One of the greatest examples of the dichotomy that arises between the different types of consequences that can be generated by the regulatory capture of digital ecosystems can be found in Meta’s recent decision not to launch its new service Threads in the European Economic Space. To the extent that its service could be interpreted as falling within the definition of a “core platform service” belonging to the category of “online social networks” (listed by the DMA), Meta decided to refrain from entering the European market, due to the disproportionate burden that the demanding obligations imposed by the DMA would entail. It should be noted that Threads is still an entrant service in the online social networking market, in contrast to the predominant position occupied by X (previously known as Twitter). In this way, we observe that the categorization as a core platform service unifies and eliminates all the nuances that free competition entails with respect to incoming services in the markets.[7]

In addition, DMA-like regulation could have additional costs for a developing economy like Brazil, where digital markets are not yet as mature as in the EU. As we have explained, while ex-ante regulation of digital markets is not warranted even when a market is mature, bigger and more developed economies may at least be able to afford the costs generated by such regulation.[8]

Some of these unintended consequences were already observable in the EU even before the DMA fully entered into force. From the perspective of users, regulation can serve to make services and products more expensive. Facebook is already trying a new business model in the EU where the consumer would see no ads (thus, there would be no data collection, or less collection of data for marketing purposes, at any rate), but would have to pay for subscriptions. Some American and European privacy-minded users may prefer this model, and would probably be able to afford it. But that is hardly the case for Latin American consumers, who on average have less than a third of the income of their European counterparts. In fact, it is arguably consumers in developing countries who have benefitted the most from digital platforms with zero-price or otherwise affordable products, such as Whatsapp and Facebook.

From the perspective of the companies that own and operate digital platforms and services, if regulations like the DMA make their platforms less profitable, some could choose not to enter or, indeed, to leave such markets. As Geoffrey Manne and Dirk Auer have explained, “to regulate competition, you first need to attract competition”:

Perhaps the biggest factor cautioning emerging markets against adoption of DMA-inspired regulations is that such rules would impose heavy compliance costs to doing business in markets that are often anything but mature. It is probably fair to say that, in many (maybe most) emerging markets, the most pressing challenge is to attract investment from international tech firms in the first place, not how to regulate their conduct.

The most salient example comes from South Africa, which has sketched out plans to regulate digital markets. The Competition Commission has announced that Amazon, which is not yet available in the country, would fall under these new rules should it decide to enter—essentially on the presumption that Amazon would overthrow South Africa’s incumbent firms.

It goes without saying that, at the margin, such plans reduce either the likelihood that Amazon will enter the South African market at all, or the extent of its entry should it choose to do so. South African consumers thus risk losing the vast benefits such entry would bring—benefits that dwarf those from whatever marginal increase in competition might be gained from subjecting Amazon to onerous digital-market regulations.[9]

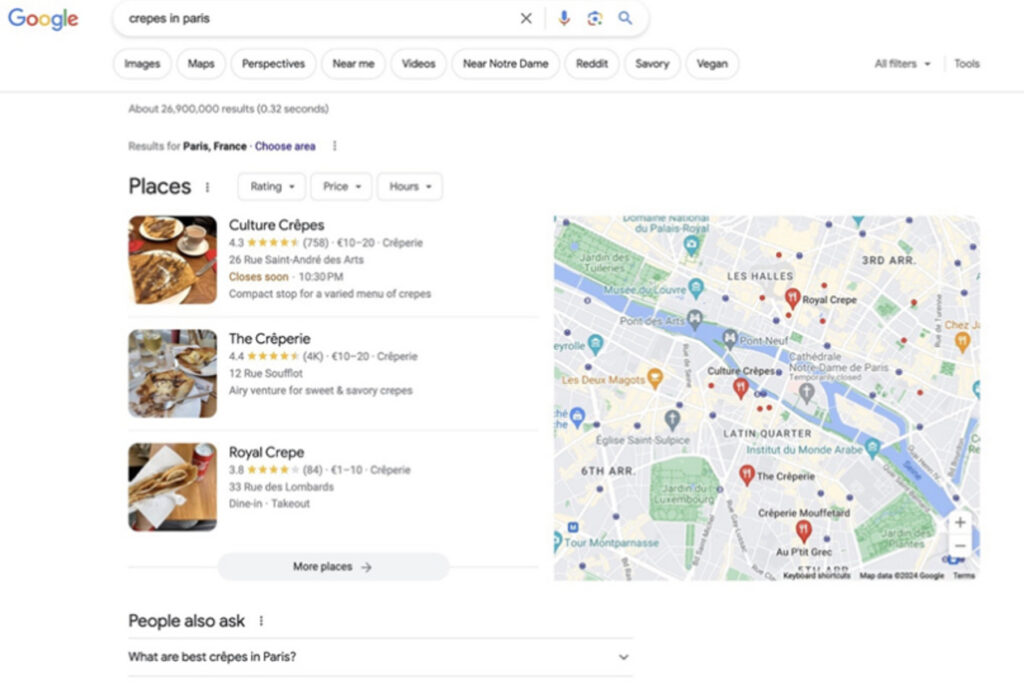

FIGURE 1: US Search Results for ‘Crepes in Paris’

SOURCE: Chamber of Progress[10]

The DMA entered into effect in full force in March 2024, and while it may be too early to reach definitive conclusions about its impact, consumers are already experiencing a degraded user experience. For example, the French newspaper Liberation has detailed how Google Maps’ map results are not showing directly in search-results pages in the same ways they once did (See Figures 1 and 2).

Presumably, this is happening because a direct link to Google Maps would constitute “self-preferencing” (See our answer to question 4, below) wherein Google, the search engine, would be “unfairly” directing traffic to its own digital-navigation service. Such conduct is prohibited by Art.6(5) of the DMA. But this kind of integration is very convenient for consumers, who can search for a restaurant and then quickly find the directions to walk or commute to it (and sometimes even book a table).

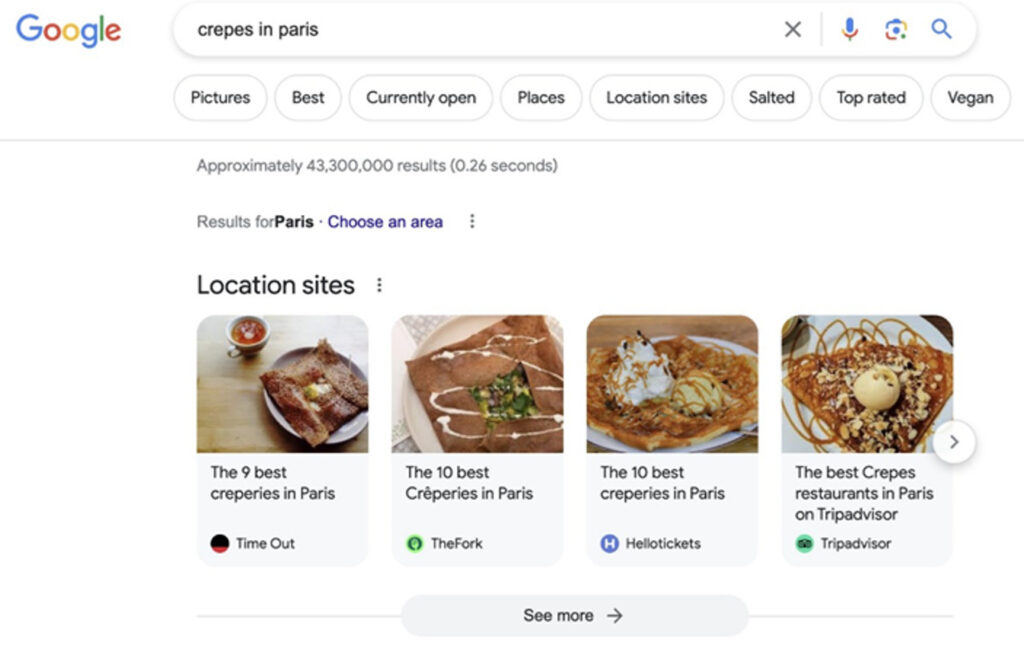

FIGURE II: French VPN Search Results for ‘Crepes in Paris’

SOURCE: Chamber of Progress[11]

While removing some features, Google is also adding more results to its results pages, because it assumes that it is required under the DMA to provide “fair” links to competing sites like Yelp and TripAdvisor.[12] In theory, the consequence of such requirements is “more options” for consumers. In practice, what consumers have is a more cluttered results page.

Apple highlights another quality-degrading consequence of the DMA: the obligation it imposes that platforms like iOS allow competing app stores and to allow apps to be downloaded directly from their websites (“sideloading”).[13] This “openness”, however, would allow that third-party applications to bypass controls and protections implemented to safeguard users’ security and privacy.[14]

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the DMA’s unintended consequences affect not only consumers, but also business users. Since Google began to implement the DMA on 19 January, 2024, early estimates suggest that clicks from Google ads to hotel websites decreased by 17.6%.[15] Presumably, this is a failure even by the DMA’s own (uncertain) standards.

1.2 Are there different reasons for regulating or not regulating different types of platforms?

This is a truly relevant question. As we have explained in our previous answer, we do not believe that digital markets generally need to be regulated. But there is an important preceding question: are these markets sufficiently similar to one another to be covered by a single body of regulation?

The terms “digital platforms” and “digital markets” are extremely broad. As was explained at a recent OECD Competition Committee meeting:

The digital economy spans from online retail to real estate listings to concert tickets to travel booking to social media. Consequently, there is not a universally defined digital market. While digital markets are dynamic and evolving, as many markets are, digital market innovations in some segments are not as groundbreaking as they once were. In a similar manner, prominent digital market characteristics are not unique to digital markets. Print newspapers are multi-sided markets. Broadcast radio is zero-price[16]” (emphasis added).

In that same vein, Herbert Hovenkamp concludes that:

… broad regulation is ill-suited for digital platforms because they are so disparate. By contrast, regulation in industries such as air travel, electric power, and telecommunications targets firms with common technologies and similar market relationships. This is not the case, however, with the four major digital platforms that have drawn so much media and political attention—namely, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. These platforms have different inputs. They sell different products, albeit with some overlap, and only some of these products are digital. They deal with customers and diverse sets of third parties in different ways. What they have in common is that they are very large and that a sizeable portion of their operating technology is digital.[17]

When dealing with platforms so different from one another—such as, e.g., Google and Nubank, or Spotify and Ebanx—it is highly unlikely that a single body of strict ex-ante rules would appropriate for them all. In some of these markets, there are clear market leaders with significant market share and few competitors. Others are more fragmented, with more evenly distributed market shares. Some markets present strong “network effects” (e.g., payment systems); while, in others, any “network effects” are much milder (e.g., streaming audio and video). Some products and platforms rely on extremely specific user data, while others work with more general data, etc.

Thus, some rules will be useless in certain markets. To the extent that they must be enforced across the board, however, they will nevertheless generate compliance costs that could be passed on to consumers, despite generating little or no benefits. For example, a data-sharing mandate like the one contained in Art.6 DMA could force gatekeepers to share data that is of little use to other platforms or “business users”. Even when the rules achieve their intended goal of helping business users, they could still negatively impact consumers. The DMA, however, does not allow for any consumer welfare or efficiency exemptions from the conduct it mandates.

1.3 To what extent does the Brazilian context approach or differ from the context of other jurisdictions that have adopted or are considering new regulations for digital platforms? Which cases, studies, or concrete examples in Brazil would indicate the need to review the Brazilian legal-regulatory framework?

The Brazilian context presents several differences from that of other jurisdictions that have adopted or are considering digital-platform regulations. These differences stem from the overall economic context, digital-market characteristics, institutional context, and previous enforcement of antitrust law in each of these divergent marketplaces.

Brazil is, of course, an important economy with tremendous potential, but it remains a developing one. Its GDP growth is projected to slow in 2024. According to the OECD, “(r)ecent reforms have reduced unnecessary bureaucracy and regulations, but further efforts are needed to reduce administrative burdens on markets for goods and services that hamper competition and productivity growth”[18]. In that vein, Brazil should be wary of rushing to pass new regulations that could discourage both local and foreign investment.

Regarding the Brazilian legal and regulatory framework, we should bear in mind that jurisdictions like the EU experimented with the use of antitrust law in digital markets for years before passing the DMA. In fact, most—if not all—of the DMA’s prohibitions and obligations stem from prior competition-law cases[19]. The EU eventually decided that it preferred to pass blanket ex-ante rules against certain practices, rather than having to litigate each through competition law. Whether or not this was the right decision is up for debate (our position is that it was not), but one thing is certain: The EU deployed its competition toolkit against digital platforms extensively before learning from those outcomes and deciding that it needed to be complemented with a new and broader set of enforcer-friendly bright-line rules.

By contrast, Brazil has initiated only a handful of antitrust cases against digital platforms. According to numbers published by CADE[20], it has reviewed 233 merger cases related to digital-platform markets between 1995 and 2023. Regarding unilateral conduct (monopolization cases)—those most relevant for the discussion of digital-market regulation, like Bill 2768/2020 already being discussed in the Brazilian Congress (hereinafter, Bill 2768)[21]—CADE opened 23 conduct cases. Of those 23 cases, nine are still under investigation, 11 were dismissed, and only three were settled via a cease-and-desist agreement. In this sense, only three cases (CDAs) out of 23 were “condemned”. It is highly questionable whether these cases provide sufficient evidence of intrinsic competition problems in digital markets.

In fact, the recent entry of companies into many of those markets suggests that the opposite is closer to the truth. There are numerous examples of entry in a variety of digital services, including the likes of TikTok, Shein, Shopee, and Daki, to name just a few.

II. Sufficiency and Adequacy of the Current Model of Economic Regulation and Defense of Competition

2.1 Is the existing legal and institutional framework for the defense of competition—notably, Law No. 12,529/2011—sufficient to deal with the dynamics of digital platforms? Are there competition and economic problems that are not satisfactorily addressed by the current legislation? What improvements would be desirable to the Brazilian System for the Defense of Competition (SBDC) to deal more effectively with digital platforms?

Yes. To be sure, as in any market, competition problems can emerge in digital markets (e.g., there may be incentives to behave anticompetitively, and some conduct could have an anticompetitive impact), but any possible anticompetitive conduct can and should be addressed by applying antitrust law (Law No. 12,529/2011).

As Colangelo and Borgogno have argued:

… recent and ongoing antitrust investigations demonstrate that standard competition law still provides a flexible framework to scrutinize several practices sometimes described as new and peculiar to app stores.

This is particularly true in Europe, where the antitrust framework grants significant leeway to antitrust enforcers relative to the U.S. scenario, as illustrated by the recent Google Shopping decision.[22]

Indeed, the European Commission has initiated procedures and even imposed fines against Google,[23] while the UK Competition and Markets Authority has settled cases with negotiated remedies against Amazon.[24] In the United States, both the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Justice Department (and several states) have initiated cases against Google,[25] Facebook,[26] and Amazon.[27]

In the same way, we think that CADE should be able to address any potential competition issues. CADE has already initiated investigations and cases related to alleged refusals to deal, self-preferencing, and discrimination against companies like Google, Apple, Meta, Uber, Booking.com, Decolar.com, and Expedia—i.e., precisely the firms that would presumably be covered by a new digital-markets regulation.

A review conducted by the OECD in 2019 concluded that “(w)hile competition law regimes in many emerging economies may still struggle to achieve enforcement goals, the Brazilian regime has largely been considered a success”[28] and that:

CADE is well-regarded within the competition practitioner community both nationally and internationally, the business community, and within the Government administration due to its technical capabilities. It is considered one of the most efficient public agencies in Brazil and its international standing as a leading competition authority both regionally and globally reinforces this domestic view that it is a model public agency.[29]

There should therefore be no doubt in that regard that CADE has the institutional tools and the technical expertise to properly deal with cases in digital markets.

Moreover, based on the EU experience, there is a risk of double jeopardy at the intersection of traditional competition law and ex-ante digital regulation. As Giuseppe Colangelo has written, the DMA is grounded explicitly on the notion that competition law alone is insufficient to effectively address the challenges and systemic problems posed by the digital-platform economy[30]. Indeed, the scope of antitrust is limited to certain instances of market power (e.g., dominance on specific markets) and of anticompetitive behavior. Further, its enforcement occurs ex post and requires extensive investigation on a case-by-case basis of what are often extraordinarily complex sets of facts. Proponents of ex-ante digital-markets regulation argue that competition law therefore may not effectively address the challenges to well-functioning markets posed by the conduct of gatekeepers, who are not necessarily dominant in competition-law terms. As a result, regimes like the DMA invoke regulatory intervention to complement traditional antitrust rules by introducing a set of ex-ante obligations for online platforms designated as gatekeepers. This also allows enforcers to dispense with the laborious process of defining relevant markets, proving dominance, and measuring market effects.

But despite claims that the DMA is not an instrument of competition law, and thus would not affect how antitrust rules apply in digital markets, the regime does appear to blur the line between regulation and antitrust by mixing their respective features and goals. Indeed, the DMA shares the same aims and protects the same legal interests as competition law.

Further, its list of prohibitions is effectively a synopsis of past and ongoing antitrust cases, such as Google Shopping (Case T-612/17), Apple (AT.40437) and Amazon (Cases AT.40462 and AT.40703). Acknowledging the continuum between competition law and the DMA, the European Competition Network (ECN) and some EU member states (self-anointed “friends of an effective DMA”) initially proposed empowering national competition authorities (NCAs) to enforce DMA obligations[31].

Similarly, the prohibitions and obligations often contemplated in proposed digital-markets regulations could, in theory, all be imposed by CADE. In fact, CADE has investigated, and is still investigating, several large companies that would likely fall within the purview of a digital-markets regulation, including Google, Apple, Meta, (still under investigation) Uber, Booking.com, Decolar.com, Expedia and iFood (settled through case-and-desist agreements). CADE’s past and current investigations against these companies already covered conduct targeted by the DMA—such as, e.g., refusal to deal, self-preferencing, and discrimination[32].[16] Existing competition law under Act 12.529/11, the Brazilian competition law, thus clearly already captures these forms of conduct.

The difference between the two regimes is that, while general antitrust law requires a showing of harm and exempts conduct that benefits consumers, sector-specific regulation would, in principle, not.

There is one additional complication. Specific regulation of digital markets (such as Bill 2768) pursues many (though not all) of the same objectives as Act 12.529/11. Insofar as these objectives are shared, it could lead to double jeopardy—i.e., the same conduct being punished twice under slightly different regimes. It could also produce contradictory results because, as pointed out above, the objectives pursued by the two bills are not identical. Act 12.529/11 is guided by the goals of “free competition, freedom of initiative, social role of property, consumer protection and prevention of the abuse of economic power” (Art. 1). To these objectives, Bill 2768 adds “reduction of regional and social inequalities” and “increase of social participation in matters of public interest”. While it is true that these principles derive from Art. 170 of the Brazilian Constitution (“economic order”), the mismatch between the goals of Act 12.529/11 and Bill 2768 may be sufficient to lead to situations in which conduct that is allowed or even encouraged under Act 12.529/11 is prohibited under Bill 2768.

For instance, procompetitive conduct by a covered platform could nevertheless exacerbate “regional or social inequalities”, because it invests heavily in one region but not others. In a similar vein, safety, privacy, and security measures implemented by, e.g., an app-store operator that typically would be considered beneficial for consumers under antitrust law[33] could feasibly lead to less participation in discussions of public interest (assuming one could easily define the meaning of such a term).

Accordingly, sector-specific regulation for digital markets could fragment Brazil’s legal framework due to overlaps with competition law, stifle procompetitive conduct, and lead to contradictory results. This, in turn, is likely to impact legal certainty and the rule of law in Brazil, which could adversely influence foreign direct investment[34].

III. Sufficiency and Adequacy of the Current Model of Economic Regulation and Defense of Competition

3. Law No. 12,529/2011 establishes, in paragraph 2 of article 36 that: “A dominant position is presumed whenever a company or group of companies is capable of unilaterally or coordinated changes in market conditions or when it controls 20% (twenty percent) or more of the relevant market, and this percentage may be changed by CADE for specific sectors of the economy”. Are the definitions of Law 12,529/2011 related to market power and abuse of dominant position sufficient and adequate, as they are applied, to identify market power of digital platforms? If not, what are the limitations?

The existence of a rule like the one contained in paragraph 2 of article 36 of Law No. 12,259/2011 is yet another reason to question any proposal to enact sector-specific regulation of digital markets. The article’s legal presumption is one of the “shortcuts” that regulations like the DMA equip competition agencies or regulators with, allegedly to avoid the administrative costs involved in defining relevant markets. This is one of the purported “benefits” of ex-ante regulation of digital markets.

But a presumption of dominance where market shares exceed 20% is not sufficient to identify digital platforms’ market power, as it would lead to too many “false positives”. It is important to note that market share alone is a misleading indicator of market power. A firm with a large market share could have little market power if it faces market substitution, potential competition, or competitors with able to increase production capacity[35].

To be sure, some competition laws around the world include dominance presumptions based on market share, but in those cases, the thresholds tend to be higher (40% or more).[36]

4. Some behaviors with potential competitive risks have become relevant in discussions about digital platforms, including: (i) economic discrimination by algorithms; (ii) lack of interoperability between competing platforms in certain circumstances; (iii) the excessive use of personal data collected, associated with possible discriminatory conduct; and (iv) the leverage effect of a platform’s own product to the detriment of other competitors in adjacent markets; among others. To what extent does the antitrust law offer provisions to mitigate competition concerns that arise from vertical or complementarity relationships on digital platforms? Which conducts with anticompetitive potential would not be identified or corrected through the application of traditional antitrust tools?

As we have explained in our answer to Question 2, any possible anticompetitive conduct in digital platforms can and should be addressed with the application of antitrust law.

There are certain types of behavior in digital markets that have been targeted by ex-ante regulations that are nevertheless capable of—or even central to—delivering significant procompetitive benefits. It would be unjustified and harmful to subject such conduct to per se prohibitions, or to reverse the burden of proof. Instead, this type of conduct should be approached neutrally, and examined on a case-by-case basis[37].

1. Self-preferencing

Self-preferencing refers to when a company gives preferential treatment to one of its own products (presumably, this type of behavior could already be caught by Art. 10, paragraph II of Bill 2768). An example would be Google displaying its shopping service at the top of search results, ahead of alternative shopping services. Critics of this practice argue that it puts dominant firms in competition with other firms that depend on their services, and that this allows companies to leverage their power in one market to gain a foothold in an adjacent market, thus expanding and consolidating their dominance. But this behavior can also be procompetitive and beneficial to users.

Over the past several years, a growing number of critics have argued that big-tech platforms harm competition by favoring their own content over that of their complementors. Over time, this argument against self-preferencing has become one of the most prominent among those seeking to impose novel regulatory restrictions on these platforms.

According to this line of argument, complementors are “at the mercy” of tech platforms. By discriminating in favor of their own content and against independent “edge providers,” tech platforms cause “the rewards for edge innovation [to be] dampened by runaway appropriation,” leading to “dismal” prospects “for independents in the internet economy—and edge innovation generally.”[38]

The problem, however, is that the claims of presumptive consumer harm from self-preferencing (also known as “vertical discrimination”) are based neither on sound economics nor evidence.

The notion that a platform’s entry into competition with edge providers is harmful to innovation is entirely speculative. Moreover, it is flatly contradicted by a range of studies that show the opposite is likely to be true. In reality, platform competition is more complicated than simple theories of vertical discrimination would have it,[39] and the literature establishes that there is certainly no basis for a presumption of harm.[40]

The notion that platforms should be forced to allow complementors to compete on their own terms—free of constraints or competition from platforms—is a flavor of the idea that platforms are most socially valuable when they are most “open.” But mandating openness is not without costs, most importantly in terms of the platform’s effective operation and its incentives for innovation.

“Open” and “closed” platforms are simply different ways to supply similar services, and there is scope for competition among these divergent approaches. By prohibiting self-preferencing, a regulator might therefore foreclose competition to consumers’ detriment. As we have noted elsewhere:

For Apple (and its users), the touchstone of a good platform is not ‘openness’, but carefully curated selection and security, understood broadly as encompassing the removal of objectionable content, protection of privacy, and protection from ‘social engineering’ and the like. By contrast, Android’s bet is on the open platform model, which sacrifices some degree of security for the greater variety and customization associated with more open distribution. These are legitimate differences in product design and business philosophy.[41]

Moreover, it is important to note that the appropriation of edge innovation and its incorporation into a platform (a commonly decried form of platform self-preferencing) greatly enhances the innovation’s value by sharing it more broadly, ensuring its coherence with the platform, providing incentivizes for optimal marketing and promotion, and the like. In other words, even if there is a cost in terms of reduced edge innovation, the immediate consumer-welfare gains from platform appropriation may well outweigh those (speculative) losses.

Crucially, platforms have an incentive to optimize openness, and to assure complementors of sufficient returns on their platform-specific investments. This does not, however, mean that maximum openness is always optimal. In fact, a well-managed platform typically will exert top-down control where doing so is most important, and openness where control is least meaningful.[42] But this means that it is impossible to know whether any particular platform constraint (including self-prioritization) on edge-provider conduct is deleterious, and similarly whether any move from more to less openness (or the reverse) is harmful.

This state of affairs contributes to the indeterminate and complex structure of platform enterprises. Consider, for example, the large online platforms like Google and Facebook. These entities elicit participation from users and complementors by making access freely available for a wide range of uses, exerting control over that access only in such limited ways as to ensure high quality and performance. At the same time, however, these platform operators also offer proprietary services in competition with complementors, or offer portions of the platform for sale or use only under more restrictive terms that facilitate a financial return to the platform. Thus, for example, Google makes Android freely available, but imposes contractual terms that require installation of certain Google services in order to ensure sufficient return.

The key is understanding that, while constraints on complementors’ access and use may look restrictive relative to an imaginary world without any restrictions, the platform would not be built in such a world the first place. Moreover, compared to the other extreme of full appropriation, such constraints are relatively minor and represent far less than full appropriation of value or restriction on access. As Jonathan Barnett aptly sums it up:

The [platform] therefore faces a basic trade-off. On the one hand, it must forfeit control over a portion of the platform in order to elicit user adoption. On the other hand, it must exert control over some other portion of the platform, or some set of complementary goods or services, in order to accrue revenues to cover development and maintenance costs (and, in the case of a for-profit entity, in order to capture any remaining profits).[43]

For instance, companies may choose to favor their own products or services because they are better able to guarantee their quality or quick delivery.[44][ Amazon, for instance, may be better placed to ensure that products provided by the Fulfilled by Amazon (FBA) logistics service are delivered in a timely manner, relative to other services. Consumers also may benefit from self-preferencing in other ways. If, for instance, Google were prevented from prioritizing Google Maps or YouTube videos in its search queries, it could be harder for users to find optimal and relevant results. If Amazon is prohibited from preferencing its own line of products on Amazon Marketplace, it might instead opt not to sell competitors’ products at all.

The power to prohibit platforms from requiring or encouraging customers of one product to also use another would limit or prevent self-preferencing and other similar behavior. Granted, traditional competition law has sought to restrict the “bundling” of products by requiring they be purchased together, but to prohibit incentivizes, as well, goes much further.

2. Interoperability

Another mot du jour is interoperability, which might fall under Art. 10, paragraph IV of Bill 2768. In the context of digital ex-ante regulation, “interoperability” means that covered companies could be forced to ensure that their products integrate with those of other firms—e.g., requiring a social network be open to integration with other services and apps, a mobile-operating system be open to third-party app stores, or a messaging service be compatible with other messaging services.

Without regulation, firms may or may not choose to make their software interoperable. But both the DMA and the UK’s proposed Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Bill (“DMCC”)[45] would empower authorities to require it. Another example is data “portability”, under which customers are permitted to move their data from one supplier to another, in much the same way that a telephone number can be retained when one changes networks.

The usual argument is that the power to require interoperability might be necessary to overcome network effects and barriers to entry/expansion. Clearly, portability similarly makes it easier for users to switch from one provider to another and, to that extent, intensifies competition or makes entry easier. The Brazilian government should not, however, overlook that both come with costs to consumer choice—in particular, by raising security and privacy concerns, while generating uncertain benefits for competition. It is not as though competition disappears when customers cannot switch services as easily as they can turn on a light. Companies compete upfront to attract such consumers through tactics like penetration pricing, introductory offers, and price wars.[46]

A closed system—that is, one with relatively limited interoperability—may help to limit security and privacy risks. This could encourage platform usage and enhance the user experience. For example, by remaining relatively closed and curated, Apple’s App Store grants users assurances that apps meet certain standards of security and trustworthiness. “Open” and “closed” ecosystems are not synonymous with “good” and “bad”, but instead represent differing product-design philosophies, either of which might be preferred by consumers. By forcing companies to operate “open” platforms, interoperability obligations could undermine this kind of inter-brand competition and override consumer choices.

Apart from potentially damaging the user experience, it is also doubtful whether some interoperability mandates—such as those between social-media or messaging services—can achieve their stated objective of lowering barriers to entry and promoting greater competition. Consumers are not necessarily more likely to switch platforms simply because they are interoperable. An argument can even be made that making messaging apps interoperable, in fact, reduces the incentive to download competing apps, as users can already interact from the incumbent messaging app with competitors.

3. Choice screens

Some ex-ante rules seek to address firms’ ability to influence user choice of apps through pre-installation, defaults and the design of app stores. This has sometimes resulted in “choice screen” mandates—e.g., requiring users to choose which search engine or mapping service is installed on their phone. But it is important to understand the tradeoffs at play here: choice screens may facilitate competition, but they do so at the expense of the user experience, in terms of the time taken to make such choices. There is a risk, without evidence of consumer demand for “choice screens”, that such rules merely impose legislators’ preference for greater optionality over what users find most convenient. Unless there is explicit public demand in Brazil for such measures, it would be ill-advised to implement a choice-screen obligation.

4. Size and market power

Many of the prohibitions and obligations contemplated in ex-ante digital-regulation regimes target incumbents’ size, scalability, and “strategic significance”. It is widely claimed that, because of network effects, digital markets are prone to “tipping”, wherein once a producer gains sufficient market share, it quickly becomes a complete or near-complete monopolist. Although they may begin as very competitive, these markets therefore exhibit a marked “winner-takes-all” characteristic. Ex-ante rules often try to avert or revert this outcome by targeting a company’s size, or by targeting companies with market power.

But many investments and innovations that would benefit consumers—either immediately or over the long term—may also serve to enhance a company’s market power, size, or strategic significance. Indeed, improving a firm’s products and thereby increasing its sales will often lead to increased market power.

Accordingly, targeting size or conduct that bolsters market power, without any accompanying evidence of harm, creates a serious danger of broad inhibition of research, innovation, and investment—all to the detriment of consumers. Insofar as such rules prevent the growth and development of incumbent firms, they may also harm competition, since it may well be these firms that are most likely to challenge the market power of firms in adjacent markets. The case of Meta’s introduction of Threads as a challenge to Twitter (or X) appears to be just such an example. Here, per-se rules adopted to prohibit bolstering a firm’s size or market power in one market may, in fact, prevent that firm’s entry into a market dominated by another. In that case, policymaker action protects monopoly power. Therefore, a much subtler approach to regulation is required.

We do not think it appropriate to reverse the burden of proof in the context of alleged competition harms in digital platforms. Without substantive evidence that such conduct causes widespread harm to a well-defined public interest (e.g., similar to cartels in the context of antitrust law), there is no justification for reversing the burden of proof, and any such reversals risk undermining consumer benefits and innovation, and discouraging investment in the Brazilian economy, out of a justified fear that procompetitive conduct will result in fines and remedies. By the same token, where the appointed enforcer makes a prima facie case of harm—whether in the context of antitrust law or ex-ante digital regulation—it should also be prepared to address arguments related to efficiencies.

5. Regarding the control of structures, is there a need for some type of adaptation in the parameters of submission and analysis of merger acts that seeks to make the detection of potential harm to competition in digital markets more effective? For example: mechanisms for reviewing acquisitions below the notification thresholds, burden of proof, and elements for analysis – such as the role of data, among others – that contribute to a holistic approach to the topic.

No, no change is needed regarding notification thresholds or analysis criteria for merger operations in digital markets. In line with our answer to Question 4 above (see 4.4, on “size and market power”), we do not think it is appropriate to reverse the burden of proof in the context of digital platforms.

As Bowman and Dumitriu show in a paper[47] analyzing a United Kingdom proposal to create special (more stringent) rules for mergers in the digital sector, mergers and acquisitions can actually enhance competition in digital markets, because:

- They are a profitable exit strategy for entrepreneurs;

- They enable an efficient “market for corporate control”;

- They can reduce transaction costs among complementary products; and

- They can support inter-platform competition.

Therefore, Bowman and Dumitriu recommend that “the government should consider a more moderate approach thar retains the balance of probabilities approach” and that, rather than reform competition laws, it should work to increase the availability of growth capital to small firms (tax breaks, financial support, etc.)[48].

There may, of course, be some challenges in applying antitrust laws to digital markets. It is often mentioned that defining relevant markets is harder in the digital context, due to their complexity and multi-sidedness, and the fact that competition is often not price-based. The rapid evolution of digital markets and the presence of network effects are also mentioned as reasons to create new rules.

Methodological difficulties do not, however, justify a major revamp of antitrust rules. Antitrust law and economics are sufficiently flexible and versatile to adapt to new markets. Modernization of the analysis and methodologies, of course, is always welcome, but that can be done within the current set of rules. Rather, it would be valuable to encourage the use of the same general analyses and tools in a wide scope of markets, so that the authority has a common benchmark and more general lessons to extract from specific cases.

IV. Design of a Possible Regulatory Model for Procompetitive Economic Regulation

5. Should Brazil adopt specific rules of a preventive nature (ex ante character) to deal with digital platforms, in order to avoid conduct that is harmful to competition or consumers? Would antitrust law—with or without amendments to deal specifically with digital markets—be sufficient to identify and remedy competition problems effectively, after the occurrence of anticompetitive conduct (ex post model) or by the analysis of merger acts?

No, there should not be absolute prohibitions on these sorts of conduct, especially without substantive experience to suggest that such conduct is always or almost always harmful and largely irredeemable (NB: Here, we answer the question in general terms; please see our answer to Question 4 for a discussion of why particular conduct (e.g., self-preferencing) should not be per-se prohibited).

Regardless of the harm to the targeted companies, overly broad prohibitions (or mandates) can harm consumers by chilling procompetitive conduct and discouraging innovation and investment. This is particularly true when no showing of harm is required and the law is not amenable to efficiencies arguments, as in the case of the DMA. The fact that such prohibitions apply to vastly different markets (for example, cloud services have little to do with search engines) regardless of context is also a sure sign that they are overly broad and poorly designed.

In fact, there are indications that, where DMA-style regulations have been introduced, it has delayed the advance of technology. For example, Google’s Bard artificial intelligence (AI) was rolled out later in Europe due to the EU’s uncertain and strict AI and privacy regulations.[49] Similarly, Meta’s Threads was not initially available in the EU, because of the constraints imposed by both the DMA and the EU’s data-privacy regulation (GDPR).[50] Twitter/X CEO Elon Musk has indicated that the cost of complying with EU digital regulations, such as the Digital Services Act, could prompt the company to exit the European market.[51]

Apart from foreclosing procompetitive conduct that benefits consumers and freezing technology in time (which would ultimately exacerbate the technological chasm between more and less advanced countries), rigid per-se rules could also apply to many budding companies that cannot be considered “gatekeepers” by any stretch of the imagination. This risk is particularly notable in the context of Brazil, given the extremely low threshold for what constitutes a “gatekeeper” enshrined in Article 9 (R$70 million, or approximately USD$14 million). Thus, many Brazilian “unicorns” could—either immediately or in the near future—be captured by these new, restrictive rules, which could in turn stunt their growth and chill innovative products. Ultimately, this would imperil Brazil’s emerging status as “[Latin America’s] most established startup hub,” and cast a shadow on what The Economist has referred to as the bright future of Latin American startups.[52][33]

The list of harmed companies could include some of Brazil’s most promising startups, such as:

- 99 (transport app)

- Neon Bank (digital bank)

- C6 Bank (digital bank)

- CloudWalk (payment method)

- Creditas (lending platform)

- Ebanx ((payment solutions)

- Facily (social commerce)

- Frete.com (road freight)

- Gympass (from corporate benefits)

- Hotmart (platform for selling digital products)

- iFood (delivery)

- Loft (rental platform)

- Loggi (logistics)

- Bitcoin Market (cryptocurrency broker)

- Merama (e-commerce)

- Madeira Madeira (home and decoration products store)

- Nubank (bank)

- Olist (e-commerce)

- Wildlife (game developer)

- Quinto Andar (rental platform)

- Vtex (technology and digital commerce)

- Unico (biometrics)

- Dock (infrastructure)

- Pismo (technology for payments and banking services)[53][34]

6.1. What is the possible combination of these two regulatory techniques (ex ante and ex post) for the case of digital platforms? Which approach would be advisable for the Brazilian context, also considering the different degrees of flexibility necessary to adequately identify the economic agents that should be the focus of any regulatory action and the corresponding obligations?

As mentioned in our answers to questions 1, 4, and 6, we don’t think there is a valid justification to regulate digital markets at the sectoral level. Therefore, there is not an “ideal” combination of ex ante and ex post intervention in such markets. Digital competition and the “rule of reason” used to analyze unilateral conduct already provide the flexibility needed to adequately identify the economic agents that should be the focus of intervention (after the fact, with actual information about the impact of specific conducts in the market) and the corresponding obligations (remedies).

7. Jurisdictions that have adopted or are considering the adoption of pro-competitive regulatory models – such as the new European Union rules, the Japanese legislation and the United Kingdom’s regulatory proposal, among others – have opted for an asymmetric model of regulation, differentiating the impact of digital platforms based on their segment of operation and according to their size, as is the case with gatekeepers in the European DMA.

7.1. Should Brazilian legislation that introduces parameters for the economic regulation of digital platforms be symmetrical, covering all agents in this market or, on the contrary, asymmetric, establishing obligations only for some economic agents?

Regulations like the DMA or Brazil’s proposed Bill 2768 contemplate thresholds (usually based on sales or the number of users) that trigger application of its prohibitions and mandates. In theory, these thresholds make said regulations more “reasonable”, in the sense they would be enforced only against digital platform that are “too big” or “too powerful”. Sales and quantity of users, however, are not reliable proxies for market power. In that sense, as we have explained in our previous answers, ex-ante regulation of digital markets would enforce “blind” rules that will ban conduct or business models that are beneficial for consumers.

Moreover, asymmetric regulation (especially absent evidence of market power by any specific economic agent) could “distort market signals and create opportunities for strategic and inefficient uses of regulatory authority by competitors”[54].

7.2. If the answer is to adopt asymmetric regulation, what parameters or references should be used for this type of differentiation? What would be the criteria (quantitative or qualitative) that should be adopted to identify the economic agents that should be subject to platform regulation in the Brazilian case?

As mentioned in our answers to questions 1, 4, and 6, we do not think there is a valid justification to regulate digital markets, much less in an asymmetric way. If, however, a regulation were to be adopted and designed to apply to only some specific market actors, it should be applied only after a finding of a large degree of market power (that is, “monopoly power” or a “dominant position”).

8. Are there risks for Brazil arising from the non-adoption of a new pro-competitive regulatory model, especially considering the scenario in which other jurisdictions have already adopted or are in the process of adopting specific rules aimed at digital platforms, taking into account the global performance of the largest platforms? What benefits could be obtained by adopting a similar regulation in Brazil?

Every approach entails risks. The question is whether adopting ex-ante rules is riskier than not adopting them, an assessment that ultimately comes down to an evaluation of error costs. In our view, there are not any significant risks (if any) of not adopting a specific regulation for digital markets and, in any case, those risks that do exist are far outweighed by the benefits. Countries that take their time to study markets, perform proper regulatory-impact analysis, and enact a serious notice-and comment-process, will be most able to learn from the experience of other regulators and markets[55]. The recent deployment of the DMA in Europe will be useful case study. South Korea, for instance, recently hit the “pause button” on its proposal to regulate digital markets—citing, among other reasons “exploring methods to regulate platforms efficiently while reducing the industry’s load”.[56]

The other side of the coin is that promptly approving regulation has costs: inefficiency, regulatory burden, and unintended consequences like less competition and inferior products delivered to consumers, as explained above. Furthermore, once ex-ante rules are passed, any ensuing costs and unintended consequences will be exceedingly difficult to reverse.

8.1. How would Brazil, in the case of the adoption of an eventual pro-competition regulation, integrate itself into this global context?

Brazil, its policymakers, regulators, and competition agencies can perfectly integrate into a global context of digitalization of markets without adopting ex-ante regulation of digital markets. Brazil can collaborate and exchange information with other policymakers and enforcement agencies under existing competition laws and forums like the OECD and the International Competition Network. With these interactions, Brazil can assure that its legal and institutional framework is up to date and that its regulations are based on evidence and solid economic theory.

Finally, only a handful of countries have adopted comprehensive ex-ante digital competition rules; namely, the EU and Germany. Others are considering their adoption, but have not done so yet (e.g., Turkey, South Africa, Australia, and South Korea). The extent to which the global context is currently defined by these new, experimental rules is thus often overstated. As argued above, Brazil should wait and see. If the new rules prove not to be what their proponents claim—as we have argued here—Brazil would derive a competitive advantage from not following suit.

V. Institutional Arrangement for Regulation and Supervision

9. Is it necessary to have a specific regulator for the supervision and regulation of large digital platforms in Brazil, considering only the economic-competitive dimension?

9.1. If so, would it be appropriate to set up a specific regulatory body or to assign new powers to existing bodies? What institutional coordination mechanisms would be necessary, both in a scenario involving existing bodies and institutions, and in the hypothesis of the creation of a new regulator?

In line with our previous answers, we do not think it is necessary to set up a new regulator or assign regulatory functions to existing agencies. Bill 2768, for instance, proposes to give ANATEL the function to oversee digital markets, building on its expertise in telecommunications regulation. Most of the proposals to regulate digital markets, however, appear to be competition-based, or at least declare the pursuit of goals similar to competition law. Therefore, the agency best-positioned to enforce such a regulation would, in principle, be CADE. Conversely, there is a palpable risk that, in discharging its duties under Bill 2768, ANATEL would transpose the logic and principles of telecommunications regulation to “digital” markets. That would be misguided, as these are two very different markets.

Not only are “digital” markets substantively different from telecommunications markets, but there is really no such thing as a clearly demarcated concept of a “digital market”. For example, the digital platforms described in Art. 6, paragraph II of Bill 2768 are not homogenous, and cover a range of different business models. In addition, virtually every market today incorporates “digital” elements, such as data. Indeed, companies operating in sectors as divergent as retail, insurance, health care, pharmaceuticals, production, and distribution have all been “digitalized.” What appears to be needed is an enforcer with a nuanced understanding of the dynamics of digitalization and, especially, the idiosyncrasies of digital platforms as two-sided markets. While CADE arguably lacks substantive experience with digital platforms, it is better-placed to enforce Bill 2768 than ANATEL because of its deep experience with the enforcement of competition policy.

Moreover, having the regulation applied by CADE would reduce the risk or “regulatory capture”. As Jean Tirole has explained:

… regulatory capture, which is one of the reasons why multi?industry regulators and competition authorities were created in the past. This raises the issue of where the new agency should be located. It could be part of the Competition authority, part of another agency (…), or a stand?alone entity. Making it part of the Competition Authority would reduce a bit the risk of capture and would also avoid the lengthy debates about which companies are really digital, which might arise if the unit is located within a sectoral regulator[57].

[1] By ex-ante regulation, we mean specific rules and duties that are sector specific (“digital markets”), whose application would not be based on the effects of the conduct regulated and where fines would apply in case of noncompliance. See Bruce H. Kobayashi & Joshua D. Wright, Antitrust and Ex-Ante Sector Regulation, The Glob. Antitrust Inst. Report on the Dig. Econ 25. (2020); See Table 1, at 869.

[2] See Robert Cooter & Tomas Ulen, Law and Economics (2000), at 40-43; W. Kip Viscusi, Joseph E. Harrington, Jr. and John M. Vernon, Economics of Regulation and Antitrust (2005), at 376-379.

[3] David S. Evans & Richard Schmalensee. Debunking The “Network Effects” Bogeyman, Regulation 39 (Winter 2017-2018) available at https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2017/12/regulation-v40n4-1.pdf.

[4] Giuseppe Colangelo, Evaluating the Case for Regulation of Digital Platforms, The Glob. Antitrust Inst. Report on the Dig. Econ 26, 930 (2020) https://gaidigitalreport.com/2020/10/04/evaluating-the-case-for-ex-ante-regulation-of-digital-platforms.

[5] We often run the risk of condemning business practices and models we don’t fully understand. Sometimes, even the businesses that implement them don’t fully know or understand the impact of such practices. See Frank H. Easterbrook, Limits of Antitrust, 63 Tex. L. Rev. 1 (1984).

[6] Jean Tirole, Competition and the Industrial Challenge for the Digital Age, 6 (2020), available at https://www.tse-fr.eu/sites/default/files/TSE/documents/doc/by/tirole/competition_and_the_industrial_challenge_april_3_2020.pdf.

[7] Alba Ribera, La Regulación de los Ecosistemas Digitales Frente a las Relaciones Complejas se los Operadores Económicos, Centro Competencia (18 Oct. 2023), https://centrocompetencia.com/regulacion-ecosistemas-digitales-relaciones-complejas-operadores-economicos. Free translation of the following text in Spanish: “Uno de los mayores ejemplos de la dicotomía que se erige entre los distintos tipos de consecuencias que se pueden generar por la captura regulatoria de los ecosistemas digitales lo podemos encontrar en la reciente decisión de Meta, de no lanzar su nuevo servicio Threads en el Espacio Económico Europeo. En la medida en que su servicio podría interpretarse de forma que cayera dentro de la definición de un “servicio básico de plataforma” perteneciente a la categoría de redes sociales en línea” (listada por la LMD), Meta decidió abstenerse de entrar en el mercado europeo, por la carga desproporcionada que le supondría las exigentes obligaciones impuestas por la LMD. Cabe notar que Threads es aún un servicio entrante en el mercado de redes sociales en línea, en contraste con la posición predominante ocupada por la actual X (anteriormente conocida como Twitter). De esta forma, observamos que la categorización como servicio básico de plataforma unifica y elimina todos los matices que el propio juego de la libre competencia opera respecto de servicios entrantes en los mercados”.

[8] Lazar Radic, Digital-Market Regulation: One Size Does Not Fit All, Truth on the Market (17 Apr. 2023), https://truthonthemarket.com/2023/04/17/digital-market-regulation-one-size-does-not-fit-all. “While perhaps the EU—the world’s third largest economy—can afford to impose costly and burdensome regulation on digital companies because it has considerable leverage to ensure (with some, though as we have seen, by no means absolute, certainty) that they will not desert the European market, smaller economies that are unlikely to be seen by GAMA as essential markets are playing a different game”.

[9] The argument presented in the article is about South Africa, but it is relevant to Brazil. See Geoffrey Manne & Dirk Auer, Brussels Effect or Brussels Defect: Digital Regulation in Emerging Markets, Truth on the Market (20 Dec. 2022), https://truthonthemarket.com/2022/12/20/brussels-effect-or-brussels-defect-digital-regulation-in-emerging-markets.

[10] Adam Kovacevich, Europe’s Digital Market Act Fails Consumers, Chamber of Progress (4 Mar. 2024), https://medium.com/chamber-of-progress/europes-digital-market-act-fails-consumers-dcaf70cc548c.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Jon Porter & David Pierce, Apple Is Bringing Sideloading and Alternate App Stores to the iPhone, The Verge (25 Jan. 2024), https://www.theverge.com/2024/1/25/24050200/apple-third-party-app-stores-allowed-iphone-ios-europe-digital-markets-act.

[14] See Apple, Complying with the Digital Markets Act (2024), available at https://developer.apple.com/security/complying-with-the-dma.pdf.

[15] Mirai, LinkedIn (Feb. 2024), https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7161330551709138945.

[16] See, The Evolving Concept of Market Power in the Digital Economy – Summaries of Contributions 6, OECD, (22 June 2022), available at https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2022)63/en/pdf.

[17] Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust and Platform Monopoly. 130 Yale L. J. 1952, 1956 (2021).

[18] Brazil Should Boost Productivity And Infrastructure Investment To Drive Growth, OECD (18 Dec. 2023), https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/brazil-should-boost-productivity-and-infrastructure-investment-to-drive-growth.htm.

[19] See Giuseppe Colangelo, The Digital Markets Act and EU Antitrust Enforcement: Double & Triple Jeopardy, Int’l Ctr. For L. and Econ. (23 Mar. 2022), https://laweconcenter.org/resources/the-digital-markets-act-and-eu-antitrust-enforcement-double-triple-jeopardy.

[20] CADE, Mercados de Plataformas Digitais, SEPN 515 Conjunto D, Lote 4, Ed. Carlos Taurisano CEP: 70.770-504 – Brasília/DF, available at https://cdn.cade.gov.br/Portal/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/estudos-economicos/cadernos-do-cade/Caderno_Plataformas-Digitais_Atualizado_29.08.pdf.

[21] See https://www.camara.leg.br/proposicoesWeb/fichadetramitacao?idProposicao=2337417.

[22] Giuseppe Colangelo & Oscar Borgogno, App Stores as Public Utilities?, Truth on the Market (19 Jan. 2022), https://truthonthemarket.com/2022/01/19/app-stores-as-public-utilities.

[23] See a list here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antitrust_cases_against_Google_by_the_European_Union.

[24] See https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/amazon-online-retailer-investigation-into-anti-competitive-practices.

[25] See https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-google-monopolizing-digital-advertising-technologies.

[26] See https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/cases-proceedings/191-0134-facebook-inc-ftc-v.

[27] See https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/09/ftc-sues-amazon-illegally-maintaining-monopoly-power.

[28] OECD, OECD Peer Reviews of Competition Law and Policy: Brazil 18 (2019), www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-peer-reviews-of-competition-law-and-policy-brazil-2019.htm.

[29] Id. at 24.

[30] Colangelo, supra note 20.

[31] How National Competition Agencies Can Strengthen the DMA, European Competition Network (22 Jun. 2021), available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/ecn/DMA_joint_EU_NCAs_paper_21.06.2021.pdf.

[32] For a detailed overview of CADE’s decisions in digital platforms and payments services, see CADE, Mercados de Plataformas Digitais, Cadernos de Cade (Aug. 2023), available at https://cdn.cade.gov.br/Portal/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/estudos-economicos/cadernos-do-cade/Caderno_Plataformas-Digitais_Atualizado_29.08.pdf.

[33] See, e.g., Epic Games, Inc. v. Apple Inc. 20-cv-05640-YGR.

[34] Joseph Staats & Glen Biglaiser, Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America: The Importance of Judicial Strength and Rule of Law, Int’l Studies Quarterly, 56(1), 193–202 (2012).

[35] Richard A. Posner & William M. Landes, Market Power in Antitrust Cases, 94 Harv. L. Rev. 937 (1980), 947-950.

[36] See, e.g., Roundtable of Safe Harbours and Legal Presumptions in Competition Law – Note by Germany 5, OECD (Dec. 2017), available at https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2017)88/en/pdf.

[37] The following is adapted from Geoffrey Manne, Against the Vertical Discrimination Presumption, Concurrences N° 2-2020, Art. N° 94267 (May 2020), https://www.concurrences.com/en/review/numeros/no-2-2020/editorial/foreword and our comments on the UK’s proposed Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers (“DMCC”) Bill: Dirk Auer, Matthew Lesh, & Lazar Radic, Digital Overload: How the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill’s sweeping new powers threaten Britain’s economy, 4 IEA Perspectives 16-21 (2023), available at https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Perspectives_4_Digital-overload_web.pdf.

[38] Hal Singer, How Big Tech Threatens Economic Liberty, The Am. Conserv. (7 May 2019), https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/how-big-tech-threatens-economic-liberty.

[39] Most of these theories, it must be noted, ignore the relevant and copious strategy literature on the complexity of platform dynamics. See, e.g., Jonathan M. Barnett, The Host’s Dilemma: Strategic Forfeiture in Platform Markets for Informational Goods, 124 Harv. L. Rev. 1861 (2011); David J. Teece, Profiting from Technological Innovation: Implications for Integration, Collaboration, Licensing and Public Policy, 15 Res. Pol’y 285 (1986); Andrei Hagiu & Kevin Boudreau, Platform Rules: Multi-Sided Platforms as Regulators, in Platforms, Markets and Innovation, (Andrei Gawer ed., 2009); Kevin Boudreau, Open Platform Strategies and Innovation: Granting Access vs. Devolving Control, 56 Mgmt. Sci. 1849 (2010).

[40] For examples of this literature and a brief discussion of its findings, see Manne, supra note 37.

[41] Brief for the International Center for law and Economics as Amicus Curiae, Epic Games v. Apple, No. 21-16506, 21-16695 (2022).

[42] See generally, Hagiu & Boudreau, supra note 30; Barnett, supra note 30.

[43] Barnett, id.

[44] See Lazar Radic & Geoffrey Manne, Amazon Italy’s Efficiency Offense. Truth on the Market (11 Jan. 2022), https://truthonthemarket.com/2022/01/11/amazon-italys-efficiency-offense.

[45] Introduced as Bill 294 (2022-23), currently HL Bill 12 (2023-24), Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill, https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3453.

[46] Joseph Farrell & Paul Klemperer, Coordination and Lock-In: Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects, 3 Handbook of Indus. Org. 3, 1967-2072 (2007).

[47] Sam Bowman & Sam Dimitriu, Better Together: The Procompetitive Effects of Mergers In Tech 9-15 (2021) The Entrepreneurs Net. & The Int’l Ctr. for L. & Econ. (2021), available at https://laweconcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/BetterTogether.pdf.

[48] Id. at 23.

[49] Clothilde Goujard, Google Forced to Postpone Bard Chatbot’s EU Launch over Privacy Concerns, Politico (13 Jun. 2023), https://www.politico.eu/article/google-postpone-bard-chatbot-eu-launch-privacy-concern.

[50] Makena Kelly, Here’s Why Threads Is Delayed in Europe, The Verge (10 Jul. 2023), https://www.theverge.com/23789754/threads-meta-twitter-eu-dma-digital-markets.

[51] Musk Considers Removing X Platform from Europe over EU Law, EurActiv (19 Oct. 2023), https://www.euractiv.com/section/platforms/news/musk-considers-removing-x-platform-from-europe-over-eu-law.

[52] The Future Is Bright for Latin American Startups, The Economist (13 Nov. 2023), https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2023/11/13/the-future-is-bright-for-latin-american-startups.

[53] See Distrito, Panorama Tech América Latina (2023), available at https://static.poder360.com.br/2023/09/latam-report-1.pdf.

[54] David L. Kaserman & John W. Mayo, Competition and Asymmetric Regulation in Long-Distance Telecommunications: An Assessment of the Evidence, 4 CommLaw Conspectus 1, 4 (1996).

[55] See Mario Zúñiga, From Europe, with Love: Lessons in Regulatory Humility Following the DMA Implementation, Truth on the Market (22 Feb. 2024), https://truthonthemarket.com/2024/02/22/from-europe-with-love-lessons-in-regulatory-humility-following-the-dma-implementation.

[56] Kwon Soon-Wan & Yeom Hyun-a, South Korea Hits Pause on Anti-Monopoly Platform Act Targeting Google, Apple, The Chosun Daily (8 Feb. 2024), https://www.chosun.com/english/national-en/2024/02/08/A4U4X6TWEFFOXF7ITCS5K6SZN4.

[57] Jean Tirole, Competition and the Industrial Challenge for the Digital Age, Inst. Fiscal. Studies (2022), at 7, available at https://ifs.org.uk/inequality/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Competition-and-the-industrial-challenge-IFS-Deaton-Review.pdf.