I. Introduction

We thank the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC” or “the Commission”) for the opportunity to offer reply comments to this notice of proposed rulemaking (“NPRM”) as the Commission seeks, yet again, to reclassify broadband-internet-access services under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934.[1]

As our previous comments, these reply comments, and the comments of others in this proceeding repeatedly point out, the idea of an “open internet” is not incompatible with business-model experimentation, which could include various experiments in pricing and network management. This is particularly apparent, given the lengthy history of broadband deployment reaching ever more consumers at ever lower cost per megabit, even in the absence of Title II regulation.

As repeatedly noted in this docket, U.S. broadband providers were able to support large increases in network load during the COVID-19 pandemic, and have been pressing forward to provide hard-to-reach potential customers with service tailored to their needs, whether through cable, fiber, satellite, fixed-wireless, or mobile connections, all without a Title II regime.

By contrast, applying Title II to broadband providers risks ossifying the existing set of technical and business-model parameters and undermining the internet’s fundamental dynamism. The ability to adapt to new applications and users has long driven the internet’s success. Declaring the current network architecture complete and frozen under Title II is at odds with this reality. In essence, openness requires embracing ongoing change, not freezing the status quo.

As noted extensively by multiple commentators in this proceeding, the rationale for applying Title II is rooted in the precautionary principle. This weak basis does not warrant preemptively imposing blanket prohibitions. A better approach would be to employ an error-cost framework that minimizes the total risk of either over- or under-inclusive rules, and to eschew proscriptive ex ante mandates.

Technology markets tend to be highly dynamic and to evolve rapidly. Which technology best fits particular deployment and usage needs, particular network designs, and the business relationships among different kinds of providers is determined by context, and by complex interactions between long-term investment and fast-changing exigencies that demand flexibility.

What this means here is that the Commission should not promulgate policies that would presumptively disallow so-called blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization. As detailed below, in most instances, there is no way to prohibit these practices ex ante without the risk of inducing a chilling effect on many pro-consumer business arrangements. Similarly, the General Conduct Standard threatens to foster an open-ended, difficult-to-predict regulatory environment that would chill innovation and harm consumers.

Going forward, the Commission should avoid Title II reclassification and instead hew to the policy that has guided it since the 2018 Order. Where problems occur, ex post enforcement of existing competition and consumer-protection laws provides enforcers with the tools sufficient to guarantee a truly open internet.

II. The Commission Fails to Offer Sufficient Justifications for a Change in Policy

The Commission imposed Title II regulations on broadband internet with its 2015 Open Internet Order.[2] Title II regulation was repealed with the 2018 Restoring Internet Freedom Order.[3] Thus, it would be reasonable to see this latest Title II proposal as a do-over of the 2015 Order. Indeed, the Commission describes its proposal as a “return to the basic framework the Commission adopted in 2015.”[4] Attorneys at Davis Wright Tremaine say the proposed rules are “effectively identical” to the Open Internet Order.[5] The American Enterprise Institute’s Daniel Lyons invokes the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s observation of bad policy as a “ghoul in a late night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried.”[6]

In ex parte meetings with FCC commissioners in 2017, ICLE concluded that the 2015 Order was not supported by a “reasoned analysis.”

We stressed that we believe that Congress is the proper place for the enactment of fundamentally new telecommunications policy, and that the Commission should base its regulatory decisions interpreting Congressional directives on carefully considered empirical research and economic modeling. We noted that the 2015 OIO was, first, a change in policy improperly initiated by the Commission rather than by Congress. Moreover, even if some form of open Internet rules were properly adopted by the Commission, the process by which it enacted the 2015 OIO, in particular, demonstrated scant attention to empirical evidence, and even less attention to a large body of empirical and theoretical work by academics. The 2015 OIO, in short, was not supported by reasoned analysis.

In particular, the analysis offered in support of the 2015 OIO ignores or dismisses crucial economics literature, sometimes completely mischaracterizing entire fields of study as a result. It also cherry picks from among the comments in the docket, ignoring or dismissing without analysis fundamental issues raised by many commenters. Tim Brennan, chief economist of the FCC during the 2015 OIO’s drafting, aptly noted that “[e]conomics was in the Open Internet Order, but a fair amount of the economics was wrong, unsupported, or irrelevant.”[7]

With the current Title II NPRM, it appears the Commission is again ignoring or dismissing fundamental issues without conducting sufficient analysis. Moreover, the see-sawing between imposition, repeal, and possible re-imposition of Title II regulations invites scrutiny under the Administrative Procedures Act, especially in light of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in Wages & White Lion Invs. LLC v. FDA.

The change-in-position doctrine requires careful comparison of the agency’s statements at T0 and T1. An agency cannot shift its understanding of the law between those two times, deny or downplay the shift, and escape vacatur under the APA. As the D.C. Circuit put it in the canonical case: “[A]n agency changing its course must supply a reasoned analysis indicating that prior policies and standards are being deliberately changed, not casually ignored, and if an agency glosses over or swerves from prior precedents without discussion it may cross the line from the tolerably terse to the intolerably mute.”[8]

As the NCTA notes in its comments:

“[A]n agency regulation must be designed to address identified problems.” Accordingly, “[r]ules are not adopted in search of regulatory problems to solve”; rather, “they are adopted to correct problems with existing regulatory requirements that an agency has delegated authority to address.” And because the reclassification of broadband would reverse previous agency decision-making, the Commission is obligated to show not only that it is addressing an actual problem, but that it reasonably believes the new rules “to be better” and has not “ignore[d] its prior factual findings” underpinning the existing rules or the “reliance interests” that have arisen from those rules. That is not possible here.[9]

The NPRM identifies two reasons for re-imposing Title II classification on broadband internet that mirror the reasons in the 2015 Order: (1) ensuring “internet openness” and (2) consumer protection. The NPRM also identifies several new justifications for reimposing Title II:

- Increased use and importance of broadband internet during and after the COVID-19 pandemic;[10]

- Federal spending on provider investments and consumer subsidies;[11]

- Safeguarding national security[12] and preserving public safety;[13] and

- The need for a uniform national regulatory system.[14]

As we discuss below, these justifications do not stand up to scrutiny.

A. Increased Importance of Broadband Internet During the COVID-19 Pandemic

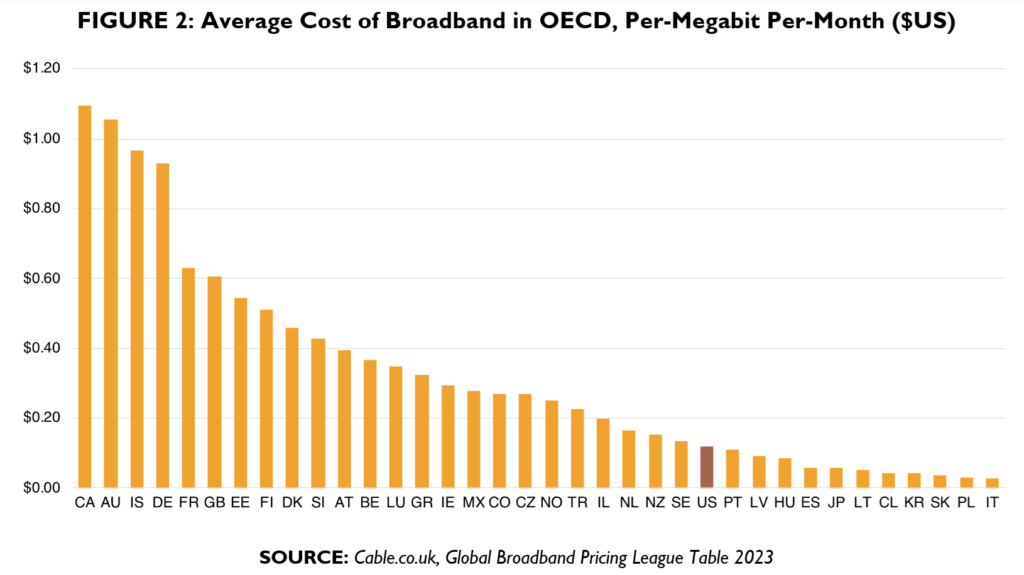

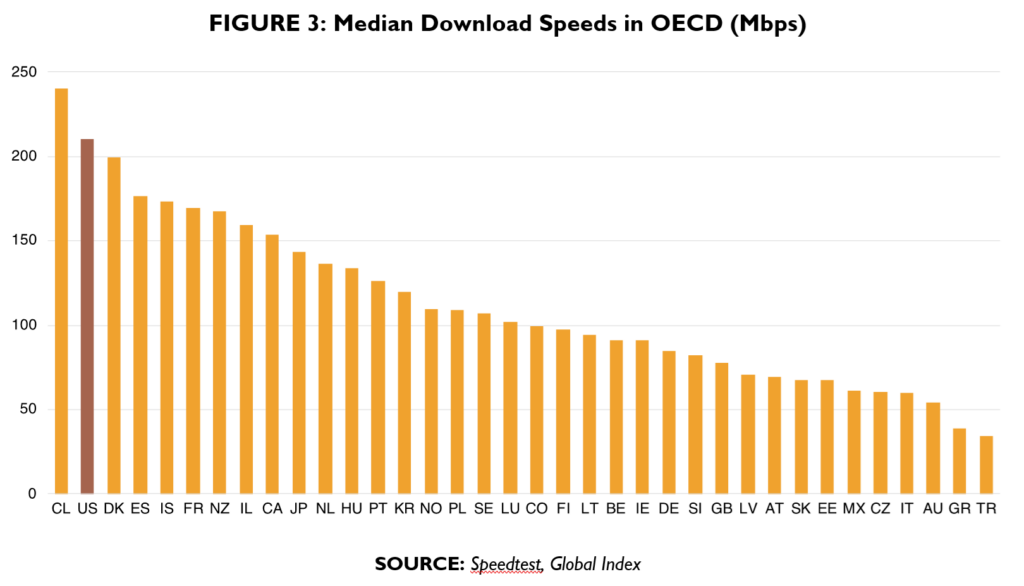

Beyond the obvious national-comparison data demonstrating that U.S. networks already outperform other countries, there are many problems with relying on internet-usage patterns during and subsequent to the COVID-19 pandemic as justification for imposing Title II regulations on broadband providers.

The NPRM concludes: “While Internet access has long been important to daily life, the COVID-19 pandemic and the rapid shift of work, education, and health care online demonstrated how essential broadband Internet connections are for consumers’ participation in our society and economy.”[15] It further notes: “In the time since the RIF Order, propelled by the COVID-19 pandemic, BIAS has become even more essential to consumers for work, health, education, community, and everyday life,”[16] and that this importance “has persisted post-pandemic.”[17] The Commission “believe[s] the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically changed the importance of the Internet today, and seek[s] comment on our belief.”[18]

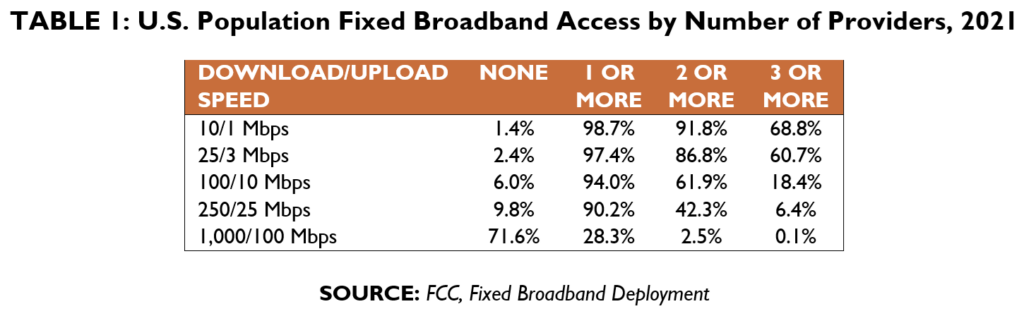

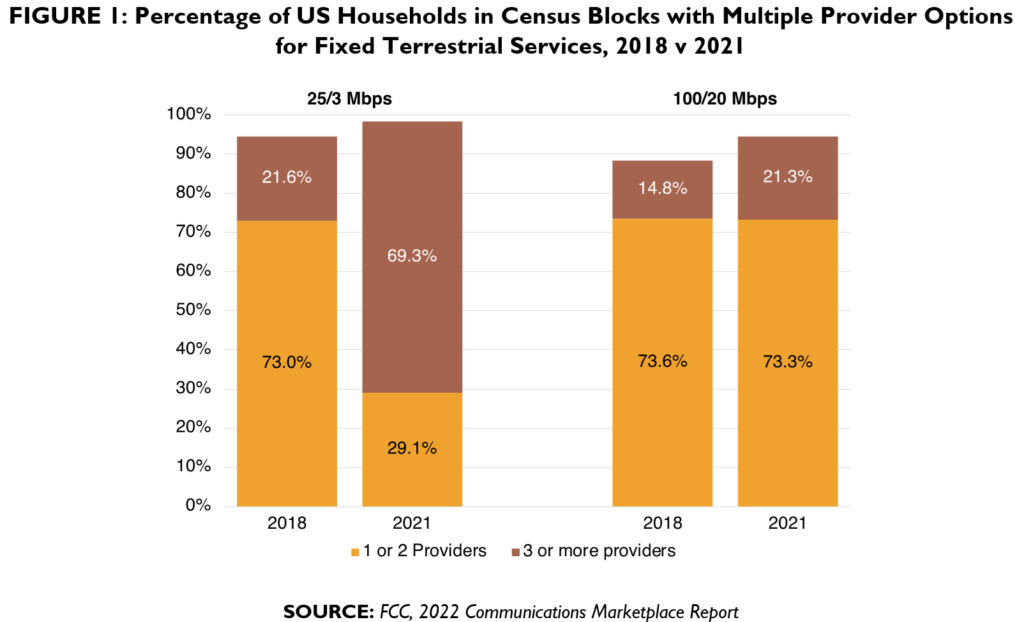

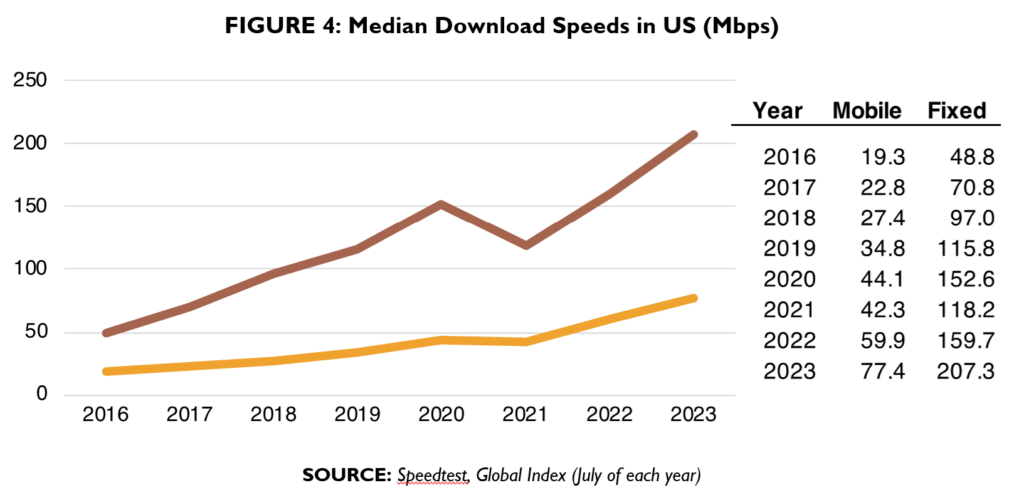

In our initial comments on this matter, ICLE reported that, by most measures, U.S. broadband competition is already vibrant, and has improved dramatically since the COVID-19 pandemic.[19] For example, since 2021, more households are connected to the internet; broadband speeds have increased while prices have declined; more households are served by more than a single provider; and new technologies—such as satellite and 5G—have served to expand internet access and intermodal competition among providers.[20]

In these reply comments, we agree with the Commission’s assertion that internet access “has long been important to daily life.” We do, however, disagree in some key respects with the Commission’s conclusion that internet access “has become even more essential,” and we question whether the pandemic has actually “dramatically changed the importance of the Internet today.” At the risk of splitting hairs, the Commission is unclear in how it defines “post-pandemic.” On April 10, 2023, President Biden signed H.J. Res. 7, terminating the national emergency related to the COVID-19 pandemic effective May 11, 2023. Thus, by the administration’s reckoning, the United States is only about nine months into the “post-pandemic” era. It is mind-boggling how the Commission could draw any firm conclusions about post-pandemic internet usage, given the dearth of information regarding internet usage over such a short period.

The NPRM attempts to support the Commission’s conclusion by citing a 2021 Pew Research Center survey “showing that high speed Internet was essential or important to 90 percent of U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.”[21] While we do not dispute Pew’s research, it seems the Commission has cherry picked from only this single report. Notably, an earlier Pew survey reported in 2017 that 90% of respondents also said high-speed internet access was essential or important.[22] By this measure, it appears the importance of the internet has not changed since 2017, let alone changed dramatically. Moreover, a COVID-era Pew survey reported that 62% of respondents said “the federal government does not have” responsibility to ensure all Americans have a high-speed internet connection at home.[23]

To support its assertion that this heightened internet usage “has persisted post-pandemic,” the Commission cites research from OpenVault, reporting that the share of subscribers using 533 GB or more of bandwidth per-month increased from 10% to almost 50% between 2017 and 2022.[24] The report cited in the NPRM, however, concludes that one factor driving the acceleration of data usage is the trend among many usage-based billing operators to provide unlimited data to their gigabit subscribers.[25] It’s more than a little ironic that providers have rolled out a policy that encourages increased data usage, only to see the FCC invoke the increased usage as a justification for regulating the policies that increased that usage. Such reasoning suggests that the Commission’s overworked “virtuous cycle” concept is nothing more than a shibboleth to be invoked only to buttress the Commission’s proposals.[26]

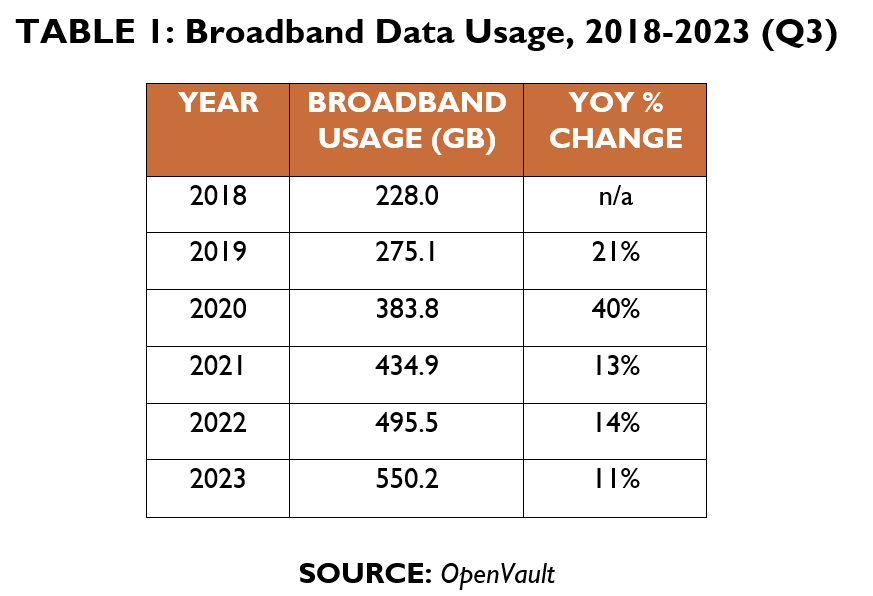

There are other areas in which the Commission seems to misunderstand the available data and how it affects its conclusions. Table 1 provides average U.S. broadband data usage reported by OpenVault for the third quarter of the years 2018 through 2023.[27] While it is true that internet usage increased by 40% in the first year of the pandemic, the increase in subsequent years (11-14%) was smaller than the average pre-pandemic increase of 20%. The average annual increase over the six years in Table 1 is 19%. It is simply too soon to tell whether COVID-19 caused a permanent shift in the rate of increase of internet usage.

To further support its assertion, the Commission reports that usage per-subscriber smartphone monthly data rose by 12% between 2020 and 2021.[28] But these years were directly in the middle of the pandemic, rendering this information useless for assessing post-pandemic mobile data usage. Information from CTIA indicates that, from 2016, wireless data traffic increased an average of 28% annually, from 13.7 trillion MB to 37.1 trillion MB.[29] By contrast, from 2019 to 2022, traffic increased by an average of only 19% a year, to 73.7 trillion MB. It appears that, rather than COVID-19 being associated with mobile data use increasing at a faster rate, the pandemic was actually associated with usage increasing at a slower rate.

Thus, not only did the performance of U.S. broadband providers during the pandemic demonstrate that Title II regulations were unnecessary, but the data that the Commission cites in this proceeding on this point completely undermine its case.

B. Recent Federal Spending on Broadband Deployment Undermines the Case for Title II

The Commission invokes “tens of billions of dollars” of congressional appropriations on internet deployment and access as a reason to impose utility-style regulation on the industry.[30] The NPRM identifies the following bills that appropriated such funds:[31]

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020) (appropriating $200 million to the Commission for telehealth support through the COVID-19 Telehealth Program);

- Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, § 903, 134 Stat. 1182, (2020) (appropriating an additional $249.95 million in additional funding for the Commission’s COVID-19 Telehealth Program) and § 904, 134 Stat. 2129 (establishing an Emergency Broadband Connectivity Fund of $3.2 billion for the Commission to establish the Emergency Broadband Benefit Program to support broadband services and devices in low-income households during the COVID-19 pandemic);

- American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, § 7402, 135 Stat. 4 (2021) (establishing a $7.171 billion Emergency Connectivity Fund to help schools and libraries provide devices and connectivity to students, school staff, and library patrons during the COVID-19 pandemic);

- Infrastructure Act, § 60102 (establishing grants for broadband-deployment programs, as administered by NTIA); § 60401 (establishing grants for middle mile infrastructure); and § 60502 (providing $14.2 billion to establish the Affordable Connectivity Program).

As we note in our comments, the legislative process would have been a perfect time for Congress to legislate net neutrality or Title II regulation, as it debated four bills that proposed spending tens of billions of dollars to encourage internet adoption and broadband buildout for the next decade or so.[32] But no such provisions were included in any of these bills, as noted in comments from the Advanced Communications Law & Policy Institute:

The Congressional record for each of these bills appears to be devoid of discussion about the inadequacy of the prevailing regulatory framework or a need to reclassify broadband. In addition, it does not appear that any bills or amendments were proposed that sought to impose common carrier regulation on broadband ISPs. An amendment that was included in the final IIJA prohibited the NTIA from engaging in rate regulation as part of BEAD. Rate regulation is not permitted under the Title I regulatory framework but would be theoretically possible under Title II. This provides additional evidence that Congress was cognizant of the regulatory environment in which it was legislating.[33]

The fact that Congress had numerous opportunities in recent years to mandate Title II regulations suggests the Commission’s proposal is likely at odds with congressional intent and that the FCC should refrain from such excessive regulatory intervention. At the very least, the pattern of congressional spending in no way supports the presumption that Title II reimposition is important, given federal outlays.

C. There Have Been No New Developments in National Security or Safety to Support Reclassification

The Commission asserts that Title II reclassification “will strengthen the Commission’s ability to secure communications networks and critical infrastructure against national security threats.”[34] The NPRM concludes, “developments in recent years have highlighted national security and public safety concerns … ranging from the security risks posed by malicious cyber actors targeting network equipment and infrastructure to the loss of communications capability in emergencies through service outages.”[35] The Commission “believe[s] that blocking, throttling, paid prioritization, and other potential conduct have the potential to impair public safety communications in a variety of circumstances and therefore harm the public.”[36]

Comments from the Free State Foundation point out the obvious: The Commission has not identified any specific national-security threats and has not articulated any way in which Title II regulations would address these threats.

Unsurprisingly, the Notice fails to articulate any specific threats of harm to national security and public safety that Title II regulation would alleviate. And the Notice provides no basis for concluding that such regulation will improve broadband cybersecurity. If security and safety truly are vulnerable, why has the Commission kept that from public knowledge until the rollout of its regulatory proposal.[37]

Comments from the CPAC Center for Regulatory Freedom suggest that the Commission’s assertions regarding national-security threats are likely based on the Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. intelligence community.[38] The latest Threat Assessment identifies potential cyber threats from China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and transnational criminal organization (TCOs).[39] The 2017 Threat Assessment, however, identified the same sources of potential threats, with TCOs divided into terrorists and criminals.[40] Broadly speaking, the United States faces cyber threats from the same sources today that it did when Title II was repealed with the RIF Order.

The “developments” identified by the Commission are not new. The 2017 Threat Assessment reported that: “Russian actors have conducted damaging and disruptive cyber attacks, including on critical infrastructure networks.”[41] The assessment also reported an Iranian intrusion into the industrial control system of a U.S. dam and criminals’ deployment of ransomware targeting the medical sector.[42] The Commission offers no evidence that these threats have changed sufficiently since the 2018 Order to justify a change in national-security posture with respect to regulating broadband internet under Title II.

The Free State Foundation criticizes the Commission’s national-security and public-safety justifications as mere speculation:

But now the Notice suddenly makes national security and public safety into primary claimed justifications for reimposing public utility regulation on broadband Internet services. Over a dozen paragraphs in the draft notice address speculated future vulnerabilities in network management operations, functionalities, and equipment.[43]

Not only are the Commission’s asserted network vulnerabilities speculative, but so are the conclusions regarding Title II regulation’s ability to address them. The NPRM “tentatively” concludes reclassification would “enhance” the FCC’s ability and efforts to safeguard national security, protect national defense, protect public safety, and protect the nation’s communications networks from entities that pose threats to national security and law enforcement.[44] Yet, it is mute on exactly how imposing Title II obligations on broadband providers would grant or enhance its powers to combat cyber-crime.

Indeed, as noted by CTIA, it is likely that many data services used in public safety would not be subject to Title II regulations:

Public Safety: The 2020 RIF Remand Order demonstrated that public safety entities often use enterprise-level quality-of-service dedicated public safety data services rather than BIAS. Title II regulation of BIAS therefore would not reach many of the data services relied on by public safety. In contrast, as the 2020 RIF Remand Order showed, the Title I framework for BIAS benefits virtually all services that advance public safety—including consumer access to information and to first responders over BIAS connectivity—as a result of the additional network investment that is better driven by Title I.[45]

FirstNet is one such service that would not be subject to Title II regulation.

FirstNet is public safety’s dedicated, nationwide communications platform. It is the only nationwide, high-speed broadband communications platform dedicated to and purpose-built for America’s first responders and the extended emergency response community. Today, FirstNet covers all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the five U.S. territories. As of September 30, 2023, 27,000 public safety agencies and direct-support organizations use FirstNet, representing more than 5.3 million connections on the network. FirstNet is designed for all first responders in the country—including law enforcement, EMS personnel, firefighters, 9-1-1 communicators, and emergency managers. It enables subscribers to maintain always-on priority access; FirstNet users never compete with commercial traffic for bandwidth, and the network does not throttle them anywhere in the country in any circumstances.

FirstNet is built and operated in a public-private partnership between AT&T and the First Responder Network Authority—an independent agency within the federal government. Following an open and competitive RFP process, the federal government selected AT&T to build, operate, and evolve FirstNet for 25 years. Custom FirstNet State Plans were developed for the country’s 56 jurisdictions, which ultimately all chose to opt in.[46]

TechFreedom also notes that Title II does not apply to data services marketed to government users.[47] The group’s comments dispel the myth that, if only the FCC had Title II authority, the legendary and nearly apocryphal Santa Clara fire-department saga could have been avoided.

For this rationale, FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel relies heavily on a single incident. In 2018, the Republican-led FCC returned broadband to Title I, the lighter regulatory approach. Months later, “when firefighters in Santa Clara, California, were responding to wildfires they discovered the wireless connectivity on one of their command vehicles was being throttled,” Rosenworcel claims. “With Title II classification, the FCC would have the authority to intervene,” she said separately.

She is mistaken. Title II doesn’t apply to data plans marketed to government users; both the 2015 Order and the NPRM define BIAS as a “mass-market retail service” offered “directly to the public.” Even if Title II had applied, the FCC’s rules wouldn’t have addressed the unique confusion that occurred in Santa Clara, which involved the fire department buying a plan that was obviously inadequate for its needs, Verizon recommending a better plan, and the department refusing. But that isn’t really the point. The point is that the FCC needed to shift its speculation about the possible impacts of blocking, throttling, or discrimination to something that seemed more tangible than abstractions like “openness.” Invoking the Santa Clara kerfuffle may make the stakes seem higher, but it won’t change how courts apply the major question doctrine.[48]

It beggars belief that the Commission would impose regulations with vast economic and political significance based on speculative threats and only tentative inklings about whether and how Title II could “enhance” the FCC’s ability and efforts to address those threats. In short, before asserting public safety as a basis for imposing Title II, the Commission needs to produce evidence demonstrating both the existence of such a problem (beyond the weak anecdote of the Santa Clara incident), as well as evidence demonstrating that the vast majority of services necessary for public safety would even be subject to Title II.

D. The Commission Must Work to Establish a National Standard for Broadband Regulation

The NPRM reports that, following the 2018 Order, “[a] number of states quickly stepped in to fill that void, adopting their own unique regulatory approaches” toward broadband internet.[49] The Commission claims “establishing a uniform, national regulatory approach” is “critical” to “ensure that the Internet is open and fair.”[50] Toward that end, the FCC now indicates it intends to pre-empt these state laws with Title II regulation and “seek[s] comment on how best to exercise [its] preemption authority.”[51] Crucially, the NPRM asks whether the proposed Title II regulations should be treated as a “floor” or a “ceiling” with respect to state or local regulations.[52]

While we believe that Title II regulation is unnecessary, unwarranted, and likely harmful to both providers and consumers, we agree with NCTA’s conclusion that, if the Commission imposes Title II regulations, those rules should be imposed and enforced uniformly nationwide as both a “floor” and a “ceiling”:

At the same time, the NPRM appropriately recognizes that broadband is an inherently interstate service, and it is critical that the states be preempted from adopting separate requirements addressing ISPs’ provision of broadband. The Commission has long recognized, on a bipartisan basis, that broadband is a jurisdictionally interstate service regardless of its regulatory classification—and the Commission can and should confirm that determination. Consistent with the initial draft of the NPRM, and contrary to any suggestion in the released version, the federal framework should not serve as a “floor” on top of which states may layer additional requirements or prohibitions. Rather, it should serve as both a floor and a ceiling. A uniform national approach is particularly vital today, as states have shown a growing desire to adopt measures that conflict with federal broadband regulation precisely because they disagree with and wish to undermine federal policy choices.[53]

If the Commission imposes Title II regulation as only a “floor,” rather than both a “floor” and a “ceiling,” then the rules will do little to eliminate the “patchwork” of state regulations about which the Commission has “expressed concern.”[54] Indeed, it is likely that the “patchwork” would become even more “patchy.” It is also likely a two-tier system of regulation would arise, much as with motor-vehicle emissions, where Environmental Protection Agency rules govern emissions for some states, but 18 other states follow California’s more stringent standards.[55] The result is a patchwork of state laws with a mishmash of emissions standards. This would be unacceptable, as the Second Circuit ruled in American Booksellers Foundation:

[A]t the same time that the internet’s geographic reach increases Vermont’s interest in regulating out-of-state conduct, it makes state regulation impracticable. We think it likely that the internet will soon be seen as falling within the class of subjects that are protected from State regulation because they “imperatively demand[] a single uniform rule.”[56]

We continue to oppose the imposition of Title II on broadband providers. With that said, whatever regulatory course the Commission charts, it is crucial that it fully preempt state law so as to avoid creating a thicket of contradictory, economically inefficient requirements that will generate unnecessary red tape on broadband providers and ultimately lead to slower deployment.

III. Title II Will Commoditize Broadband Services and Stifle Innovation

Before discussing the NPRM’s particulars, it is important to note that regulatory humility is crucial when dealing with industries and firms that develop and deploy highly innovative technologies.[57] It remains a daunting challenge to forecast the economics of technological innovation on the economy and society. The potential for unforeseen and unintended consequences—particularly in hindering the development of new ways to serve underserved consumers—is considerable. Such regulatory actions could have profound and far-reaching effects. In particular, it can serve to eliminate many of the dimensions across which providers compete. The result would be to remove much of the product differentiation among competitors and turn broadband service into something more like a commodity service.

The Commission’s proposed Title II regulation of broadband internet seeks to prohibit blocking, throttling, or engaging in paid or affiliated prioritization arrangements, and would impose a “general conduct standard” that it claims would prohibit “interference or unreasonable disadvantage to consumers or edge providers.”[58] But the Commission has not identified any actual harms from these practices or any actual benefits that would flow from banning or limiting them, or from placing deployment under a broad discretionary standard. Indeed, the NPRM identifies only four concrete examples of alleged blocking or throttling.[59]

- A 2005 consent decree by DSL-service provider Madison River requiring it to discontinue its practice of blocking Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) telephone calls.[60] At the time, Madison River had fewer than 40,000 DSL subscribers.[61]

- A 2008 order against Comcast for interfering with peer-to-peer file sharing.[62] Comcast claimed intensive file-sharing traffic was causing such severe latency and jitter that it made VoIP telephony unusable.[63]

- A study published in 2019, using data mostly from 2018, that “suggested that ISPs regularly throttle video content.”[64] Several commenters note that this study has been “debunked.”[65] We note in our comments that the study found that, whatever throttling ISPs engaged in, the authors concluded it was “not to the extent in which consumers would likely notice.”[66]

- In 2021, a small ISP in northern Idaho planned to block customer access to Twitter and Facebook; responding to public pressure, the provider backtracked on the policy.[67]

The first two examples are now more than 15 years old and provide no useful information regarding current or future conduct by broadband-internet-service providers. The third example is of questionable reliability. The fourth example is of a policy that was never fully implemented and was, indeed, rectified because of the pressures of market demand.

The Commission seems to be missing, ignoring, or dismissing a key fact: The powers it seeks under Title II are unnecessary and unwarranted, and—in many cases—it already has the power to deter harmful conduct. For example, Scalia Law Clinic finds “no credible evidence of internet service providers engaging in blocking, throttling, or anticompetitive paid prioritization.”[68]

TechFreedom notes:

The FCC could still police surreptitious blocking, throttling, or discrimination among content, services, and apps—but then, the Federal Trade Commission can already do that; it just hasn’t needed to.[69]

ITIF’s comments explain how the 2018 Order’s transparency requirements have stifled incentives to engage in undisclosed blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization, to the point that the largest providers have publicly indicated they don’t—and won’t—engage in such practices:

Harmful violations of basic net neutrality principles are exceedingly rare, and there is no evidence of them since the 2018 reapplication of the Title I regime the FCC now looks to unwind. Much of the heavy lifting of the bright line requirements is already functionally in practice. Many major ISPs have publicly foresworn blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization. The RIF’s transparency requirements ensure that these practices cannot happen in secret. Therefore, to the extent a flat ban might deter the few harmful attempts that might get through, its benefits would likely be counterbalanced by the broader chilling effects of Title II.[70]

As much as the Commission would like to expand its reach across other agencies, CTIA notes that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been “active” in monitoring providers’ practices:

In any event, BIAS providers have made meaningful commitments to their customers, in keeping with the transparency rule, not to block or throttle or engage in paid prioritization, which the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) can enforce under many circumstances. And the FTC has been active in scrutinizing broadband provider practices following adoption of the 2018 RIF Order.[71]

As we note in our comments, the U.S. broadband industry is both competitive and dynamic. This vigorous competition forces providers to align their interests with those of their customers, both consumers and edge providers, as noted by CTIA:

Despite the Notice’s suggestion, regulation in a handful of states has not affected what these thousands of BIAS providers do, because it remains in their interest to offer customers service that does not block, throttle, or engage in paid prioritization. In addition, the Notice does not identify a list of harms arising since the 2018 RIF Order, and even Internet openness allegations against BIAS providers are, for all practical purposes, non-existent.[72]

More broadly, a survey of the research summarized by Roslyn Layton and Mark Jamison concludes that, with the exception of some bans on blocking, “net neutrality” regulations would do more harm than good to both consumers and providers:

But in general, the literature finds that regulations would hinder investment and harm consumers, but not under all conditions. The exception is for traffic blocking, where there is broad agreement that consumers are worse off with blocking. The literature supported the conclusion that paid prioritisation would lead to lower retail prices for broadband access and provide financial resources for network expansion. Jamison concludes that because the scenarios that give different answers are each feasible and may exist at different times, it seems that policy should favour applying competition and consumer protection laws, which can be adapted to individual cases, rather than ex ante regulations, which necessarily apply broadly[73]

And as CTIA notes:

The practical benefit of rules banning blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization would be negligible, as no such behavior exists, but the costs of reclassification to Title II would be substantial, as the switch to Title II regulation raises the specter of further regulation at the Commission’s whim, generating regulatory uncertainty that harms the Commission’s stated goals.[74]

In summary, the Commission has only speculated about whether blocking, throttling, or paid or affiliated prioritization currently exists, or would exist in the future without Title II regulation. It further speculates with respect to potential harms, and ignores or dismisses the benefits from these practices. In reality, there is no evidence to suggest that there is systematic abuse along these lines.

A. Economic Logic and the Economic Literature Support Non-Neutral Networks[75]

Tim Wu, widely credited with coining the term “net neutrality,” has argued that even a “zero-pricing rule” should permit prioritization:

As a result, we do not feel as though a zero-pricing rule should prohibit this particular implementation, as here content providers are not forced to pay a termination fee to access users.[76]

Moreover, it is important to note that not all innovation comes from small, startup edge providers. As economists Peter Klein and Nicolai Foss have pointed out:

The problem with an exclusive emphasis on start-ups is that a great deal of creation, discovery, and judgment takes place in mature, large, and stable companies. Entrepreneurship is manifest in many forms and had many important antecedents and consequences, and we miss many of those if we look only at start-up companies.[77]

Adopting a regulatory schema that prioritizes startup innovation (although, as noted, it likely doesn’t even do that) at the expense of network innovation—in part, because network operators aren’t small startups—may materially detract from consumer welfare and the overall rate of innovation.

In effect, net neutrality claims that the only proper price to charge content providers for access to ISPs and their subscribers is zero. As an economic matter, that is possible. But it most certainly needn’t be so.

At the most basic level, it is simply not demonstrably the case that content markets themselves are best served by being directly favored, to the exclusion of infrastructure. The two markets are symbiotic, in that gains for one inevitably produce gains for the other (i.e., increasing quality/availability of applications/content drives up demand for broadband, which provides more funding for networking infrastructure, and increased bandwidth enabled by superior networking infrastructure allows for even more diverse and innovative applications/content offerings to utilize that infrastructure). Absent an assessment of actual and/or likely competitive effects, it is impossible to say ex ante that consumer welfare in general—and with regard to content, in particular—is best served by policies intended to encourage innovation and investment in one over the other.

To the extent that new entrants might threaten ISPs’ affiliated content or services, the Commission’s proposal is on somewhat more solid economic ground. But such a risk justifies, at most, only a limited rule that creates a rebuttable presumption of commercial unreasonableness. Even then, the logic behind such a rule tracks precisely the well-established antitrust law and economics of vertical foreclosure, which neither justifies a presumption (even a rebuttable one), nor the imposition of a targeted regulation beyond the antitrust laws themselves.[78]

1. Economic literature

The use of paid prioritization as a means for ISPs to recover infrastructure costs raises the fundamental empirical question that has largely remained unaddressed: whether the benefits of mandated “openness” outweigh the forsaken benefits to consumers, infrastructure investment, and competition from prohibiting discrimination.

A related question was considered by Tim Wu, who acknowledged that there were inherent tradeoffs in mandating neutrality. Among other things, prohibiting content prioritization (thus precluding user subsidies) raises consumer prices:

Of course, for a given price level, subsidizing content comes at the expense of not subsidizing users, and subsidizing users could also lead to greater consumer adoption of broadband. It is an open question whether, in subsidizing content, the welfare gains from the invention of the next killer app or the addition of new content offset the price reductions consumers might otherwise enjoy or the benefit of expanding service to new users.[79]

Policy advocates that support net neutrality routinely misunderstand this dynamic, and instead seem to presume that discrimination by ISPs can only harm networks. As Public Knowledge has claimed, for instance:

If Verizon – or any ISP – can go to a website and demand extra money just to reach Verizon subscribers, the fundamental fairness of competing on the internet would be disrupted. It would immediately make Verizon the gatekeeper to what would and would not succeed online. ISPs, not users, not the market, would decide which websites and services succeed.

* * *

Remember that a “two-sided market” is one in which, in addition to charging subscribers to access the internet, ISPs get to charge edge providers on the internet to access subscribers as well.[80]

And elsewhere:

Comcast’s market power affords it advantages vis-à-vis recipients of Internet video content as well as creators of Internet video content. For example, Comcast will be able to distribute NBC content through its Xfinity online offering without having to pay itself license fees.

This two-sided market advantage results from Comcast’s position as a gatekeeper: it provides access to customers for content creators and it provides access to content for customers. Control over both directions of this transaction allows Comcast the opportunity for anticompetitive behavior against either content creators or consumers, or both simultaneously.[81]

These comments fundamentally misunderstand the economics of two-sided markets: Rather than facilitating anticompetitive conduct or enabling greater exploitation of both sides of the market, two-sided markets facilitate efficient but otherwise-difficult economic exchange, and nearly all such markets incorporate subsidies from one side of the market to the other—not excessive profiteering by the platform.[82] The “two-sidedness” of markets does not inherently confer increased ability to earn monopoly profits. In fact, the literature suggests that the availability of subsidization reduces monopoly power and increases welfare. In the broadband context, as one study notes:

Imposing rules that prevent voluntarily negotiated multisided prices will never achieve optimal market results, and…can only lead to a reduction in consumer welfare.[83]

Business models frequently coexist where different parties pay for the same or similar services. Some periodicals are paid for by readers and offer little or no advertising; others charge a subscription and offer paid ads; and still others are offered for free, funded entirely by ads. All of these models work. None is necessarily “better” than another. Indeed, each model may be better than the others under each model’s idiosyncratic product and market conditions. There is no reason the same wouldn’t be true for broadband and content.

What’s more, the literature directly contradicts the assumption that net neutrality improves consumer welfare or encourages infrastructure investment. In fact, the opposite appears to be true, and non-neutrality actually generally benefits both consumers and content providers:

Our main result is that a switch from the net neutrality regime to the discriminatory regime would be beneficial in terms of investments, innovation and total welfare. First, when ISPs offer differentiated traffic lanes, investment in broadband capacity increases. This is because the discriminatory regime allows ISPs to extract additional revenues from CPs [Content Providers] through the priority fees. Second, innovation in services also increases: some highly congestion-sensitive CPs that were left out of the market under net neutrality enter when a priority lane is proposed. Overall, discrimination always increases total welfare….[84]

Another paper finds the same result, except in a small subset of cases:

Our results suggest that investment incentives of ISPs, which are important drivers for innovation and deployment of new technologies, play a key role in the net neutrality debate. In the non-neutral regime, because it is easier to extract surplus through appropriate CP pricing, our model predicts that ISPs’ investment levels are higher; this coincides with the predictions made by the defendants of the non-neutral regime. On the other hand, because of platforms’ monopoly power over access, CP participation can be reduced in the non-neutral regime; this coincides with the predictions made by the defendants of the neutral regime. We find that in the walled-garden model, the first effect is dominant and social welfare is always larger in the non-neutral model. While this still holds for many instances of the priority-lane model, the neutral regime is welfare superior relative to the non-neutral regime when CP heterogeneity is large.[85]

The economic literature does, however, provide some support for imposing a minimum-quality standard:

We extend our baseline model to account for the possibility that ISPs engage in quality degradation or “sabotage” of CP’s traffic. We find that sabotage never arises endogenously under net neutrality. In contrast, under the discriminatory regime, ISPs may have an incentive to sabotage the non-priority lane to make the priority lane more valuable, and hence, to extract higher revenues from the CPs that opt for priority. Any level of sabotage is detrimental for total welfare, and therefore, a switch to the discriminatory regime would still require some regulation of traffic quality.[86]

Even here, however, the analysis does not consider disclosure-based (transparency) restraints on quality to be degradation, and it is entirely possible that a transparency rule (or simply the risk of public disclosure, even without such a rule) would be sufficient to deter quality degradation.

In the end, the literature to date supports, at most, a minimum-quality requirement and perhaps only a transparency requirement; it does not support mandated nondiscrimination rules.

B. Paid Prioritization

The Commission “does not dispute” that there may be benefits associated with paid prioritization.[87] Yet it “tentatively” concludes that the “potential” harms “outweigh any speculative benefits.”[88] To be blunt, the Commission is just guessing, as summarized by TPI:

The argument that paid prioritization was necessarily a net harm to society was always an unproven hypothesis. The test still has not been conducted, making it impossible to draw the conclusion that it would necessarily be bad.[89]

Indeed, both the economics of nonlinear pricing, and the evidence already added to the record, demonstrate that the Commission should not ban paid prioritization.

1. Paid prioritization is a necessary feature of providing internet service

First, as we have previously noted before the Commission, simply banning paid prioritization does not remove the need to ration broadband in a resource-constrained environment:

Scarcity on the Internet (as everywhere else) is a fact of life — whether it arises from network architecture, search costs, switching costs, or the fundamental limits of physics, time and attention. The need for some sort of rationing (which implies prioritization) is thus also a fact of life. If rationing isn’t performed by the price mechanism, it will be performed by something else. For startups, innovators, and new entrants, while they may balk at paying for priority, the relevant question, as always, is “compared to what?” There is good reason to think that a neutral Internet will substantially favor incumbents and larger competitors, imposing greater costs than would paying for prioritization. Far from detracting from the Internet’s value, including its value to the small, innovative edge providers so many net neutrality proponents are concerned about, prioritization almost certainly increases it.[90]

Essentially, banning “paid prioritization” does nothing to actually remove the need for prioritization. Instead, it merely moves the locus of decision-making out of the scope of a market made of arm’s-length transactions, and puts it into the hands of a few individuals at the Commission.

Broadband-internet access is a valuable service that requires ongoing investments and maintenance. Determining who pays for broadband access is a complex economic issue. In multi-sided markets like broadband, rigid one-size-fits-all pricing models are often inadequate. Instead, experimentation and flexibility are needed to find optimal and sustainable cost allocations between consumers and industry. Multiple business models can reasonably coexist, with costs shared in various ways.[91] Overall, broadband pricing should balance economic sustainability, consumer affordability, and the public interest.

Pricing models across industries demonstrate that there is no single best approach. For example, as with periodicals (discussed above), some websites rely entirely on subscription fees, others use a mix of subscriptions and advertising, and some are given away for free and supported solely by ads. All of these models can work, and all may appeal to different consumer segments. Similarly, for emerging data and content services that intend to attract new users, pricing flexibility and experimentation are needed. There is no one-size-fits-all model inherently superior in reaching consumers or promoting consumer welfare. The optimal strategy depends on market dynamics and consumer demand, which are uncertain and evolving in new markets. Rigid pricing mandates risk stifling innovation and growth.

Moreover, the assumption that paid prioritization inherently favors incumbents over new entrants is flawed. In many cases, new entrants are at a disadvantage with respect to incumbents. Incumbents may have any number of many advantages, including brand loyalty, mature business processes, economies of scale, etc. But prioritization can reduce the scope and scale of some of these advantages:

[P]remium service stimulates innovation on the edges of the network because lower-value content sites are better able to compete with higher-value sites with the availability of the premium service. The greater diversity of content and the greater value created by sites that purchase the premium service benefit advertisers because consumers visit content sites more frequently. Consumers also benefit from lower network access prices.[92]

Thus, there must be some evidence presented that paid prioritization benefits incumbents at the expense of new entrants before this claim can be taken seriously. There may be some cases where this is so, but it’s absolutely not a warranted presumption, and should be demonstrated as a realistic harm before it is categorically forbidden.

As noted, non-neutrality offers the prospect that a startup might be able to buy priority access to overcome the inherent disadvantage of newness, and to better compete with an established company. Neutrality, on the other hand, renders that competitive advantage unavailable; the baseline relative advantages and disadvantages remain—all of which helps incumbents, not startups. With a neutral internet, the incumbent competitor’s in-built advantages can’t be dissipated by a startup buying a favorable leg-up in speed. The Netflixes of the world will continue to dominate.

Of course, the claim is that incumbents will use their huge resources to gain even more advantage with prioritized access. Implicit in this claim must be the assumption that the advantage a startup could gained from buying priority offers less potential return than the costs imposed by the inherent disadvantages of reputation, brand awareness, customer base, etc. But that’s not plausible for all startups. Investors devote capital there is a likelihood of a good return. If paying for priority would help overcome inherent disadvantages, there would be financial support for that strategy.

Also implicit is the claim that the benefits to incumbents (over and above their natural advantages) from paying for priority—in terms of hamstringing new entrants—will outweigh the cost. This, too, is unlikely to be true, in general. Incumbents already have advantages. While they might sometimes want to pay for more, it is precisely in those cases where it would be worthwhile that a new entrant would benefit most from the strategy—ensuring, again, that investment funds will be available.

Finally, implicit in these arguments is the presumption that content deserves to be subsidized, while networks need neither subsidy nor the flexibility to adopt business models that increase returns or help to operate their networks optimally. But broadband providers, equipment makers, and the like have spent trillions of dollars to build internet infrastructure. The “neutrality for startups” argument holds that content providers shouldn’t be the ones to pay for it, but it maintains this without evidence that mandating subsidies to content providers (in the form of zero-price internet access) will actually lead to optimal results.[93]

While paid prioritization does carry risks, the impacts on competition are nuanced. Claims that it necessarily harms new entrants and benefits only incumbents oversimplify a complex issue. The real impacts likely depend on the specifics of how prioritization is implemented in a given market.

The notion that businesses’ internet-access costs should be zero reflects flawed thinking. Access is never truly zero-cost—all businesses have costs. Early-stage startups, in particular, need capital to cover expenses as they grow. Singling out broadband access as uniquely important for price parity is questionable. One could make equivalent arguments for controlling other business costs like rent, advertising, personnel, etc. Businesses rationally factor the costs of key resources into their planning and investments. Some enjoy cost advantages in certain areas, and disadvantages in others. Whether “equal” pricing is mandated across businesses is often irrelevant to long-term investment decisions. While fair-access policies have merits, the costs of resources like internet access are just one factor among many that businesses must weigh.

This is not an argument unique to broadband service pricing. “Paid prioritization” is a pricing technique that occurs in many other areas, and frequently is useful for solving rationing problems. And where it is banned, this yields downstream effects that we would similarly expect to occur in the broadband market. As the Nobel Laureate economist Ronald Coase pointed out, banning paid prioritization for radio airplay (i.e., payola) actually benefits large record labels at the expense of smaller artists.[94] Simply banning payola, however, did nothing to rectify the underlying problem: airtime on radio was scarce and radio stations had to resort to other ways to ration it. As with insider trading, [95] the de facto practice necessarily is reconstituted elsewhere. The dollars previously spent on payola simply end up somewhere else, such as in advertising.[96] On the radio, this meant more ads taking up airtime, creating more scarcity and less music of any kind. While the specific mix of actual songs played may be different, there is no reason to believe it is in any way “better” or even more diverse without payola, and every reason to believe that there will simply be less of it.

Retail-store slotting contracts provide another helpful analogy:

Retailer supply of shelf space can therefore be thought of as creating incremental or “promotional” sales that would not occur without the promotion. The promotional shelf space provided by retailers induces these incremental sales by increasing the willingness of “marginal consumers” to pay for a product that they would not purchase absent the promotion. The generation of these promotional sales may occur by more prominently displaying a known brand, for example, in eye-level shelf space or a special display, or by providing shelf space for an unknown or new product.[97]

As with prioritization on the internet, an intuitive fear about such arrangements is that they will be used by established content providers to hamstring their rivals:

The primary competitive concern with slotting arrangements is the claim that they may be used by manufacturers to foreclose or otherwise disadvantage rivals, raising the costs of entry and consequently increasing prices. It is now well established in both economics and antitrust law that the possibility of this type of anticompetitive effect depends on whether a dominant manufacturer can control a suf?cient amount of distribution so that rivals are effectively prevented from reaching minimum ef?cient scale.[98]

The problem with this argument is that:

[S]lotting fees are a payment that must be borne by all manufacturers. Competition for shelf space that leads to slotting may raise the cost of obtaining retail distribution, but it does so for everyone…. However, competition between incumbents and entrants for retail distribution generally occurs on a level playing field in the sense that all manufacturers can openly compete for shelf space and it is the manufacturer willing to pay the most for a particular space that obtains it.[99]

While not a violation of antitrust law, the NPRM’s approach would ban this practice without evidence of harm. So long as there are minimum-service guarantees in place, however, there is no reason to believe that the practice would actually harm startups or consumers. Moreover, these sorts of arrangements are usually tailored to the firms in question, with larger firms that demand more service also drawing higher prices for that service. Thus, in practice, the opportunity to pay for prioritization is relatively less attractive to large firms.

A blanket ban on paid prioritization risks locking in inefficient and suboptimal pricing models. It would restrict the very experimentation and innovation in business models that could help expand internet access. Rather than a one-size-fits-all ban, tailored oversight and monitoring of prioritization practices through the existing transparency rules would better balance the complex tradeoffs involved.

In the NPRM, the Commission notes that “In adopting a ban on paid prioritization in 2015, the Commission sought to prevent the bifurcation of the Internet into a ‘fast’ lane for those with the means and will to pay and a “slow” lane for everyone else.”[100] It then tentatively concludes that this concern remains valid today. But this framing makes as little sense now as it did in 2015.

The concept of “fast lanes” is a gross oversimplification, even apart from paid-prioritization schemes. In most cases, prioritization involves applying network-management strategies to guarantee certain content meets minimum-performance levels appropriate for its data type. For example, this could include prioritizing video-conferencing data for lower latency, or streaming video for better throughput. Technically, this creates a “fast lane,” but it is highly misleading to refer to it as such.

The costs and benefits of prioritization are nuanced and context-dependent. Whether prioritization is beneficial or harmful depends heavily on the presence of congestion. Prioritization matters most when congestion exists, since it inherently involves improving service for some content at the expense of other content.[101] While prioritization schemes risk worsening service for non-prioritized content, they also can improve quality for higher-value applications. Congestion levels, minimum standards, and other factors combined to determine the impact. Overly simplistic “fast lane” rhetoric should be avoided in favor of careful analysis of the tradeoffs, given technical and market conditions. What works as a better default is to provide minimum-performance guarantees for internet service.

A minimum-performance guarantee means that prioritized services cannot degrade non-prioritized content below a certain level. It also limits the extent to which prioritized content can receive better service, given the bandwidth needed to satisfy the minimum guarantees. As a result, ISPs that offer prioritization may actually increase total network capacity to deliver meaningful priority benefits without violating minimums. [102]

Even without expanded capacity, prioritization with minimum guarantees does not necessarily create starkly differentiated service levels. During congestion, “slower” service becomes a reality for non-prioritized content. But simultaneously, the meaningfulness of “faster” service decreases in proportion to congestion levels. The practical difference between prioritized and non-prioritized traffic is less than is often assumed, and varies based on fluctuating traffic volumes. With appropriate safeguards, the fears of dramatic disparities created by “fast lanes” are overblown. For latency-insensitive content, even degraded “slow lanes” would have minimal effect. Thus, even if prioritization were to become widespread, its value and price would likely decrease. More content providers could thereby afford priority, further lessening any differentiation. With marginal speed differences and cheap priority access, dramatic impacts are unlikely.

We see the same dynamic even within edge providers’ operations with respect to what are glibly deemed “slow” and “fast” lanes on the open internet. For example, it was discovered in 2015 that Netflix had been throttling its own transmission rate in certain situations, likely in order to optimize customers’ viewing experience.[103] But under the framing presented in this NPRM, the incentive for this sort of self-disciplining behavior—which optimally rations scarce network resources—would disappear.

2. The record reflects that the Commission should not ban paid prioritization

As we discuss below, the Commission asserts that “minimal” compliance costs are associated with a ban on blocking and a “minimal” compliance “burden” is associated with a ban on throttling. The Commission has no principled means to make this determination.

CEI’s comments point out the obvious: Paid prioritization is ubiquitous, even in the federal government, with TSA PreCheck and USPS Priority Mail,[104] as well as paid priority (i.e., “expedited service”) for passports.[105] The Federal Highway Administration not only condones paid prioritization of roadways (e.g., high-occupancy toll lanes, or “HOT lanes”), it encourages them, concluding that:

HOT lanes provide a reliable, uncongested, time saving alternative for travelers wanting to bypass congested lanes and they can improve the use of capacity on previously underutilized HOV lanes. A HOT lane may also draw enough traffic off the congested lanes to reduce congestion on the regular lanes.[106]

In our comments on this matter, we note that the Commission fails to distinguish between instances where so-called “paid prioritization” has pro-consumer benefits and where it may constitute an anticompetitive harm.[107] For example, Netflix’s collocation of data centers within different networks to expedite service and reduce overall network load are unequivocally pro-consumer.[108] In addition, AT&T’s Sponsored Data program and T-Mobile’s Binge On offerings provide more choices, potentially lower prices, and introduce competitive threats to other providers in the market.[109]

Under the Commission’s proposed Title II regulations, these innovations would be illegal. As a result, as ITIF points out, firms and potential entrants would have reduced incentives to experiment with and roll out new and innovative services to a wide range of consumers, especially lower-income consumers:

In the case of paid prioritization there would be significant harm to presuming conduct unlawful. The 2017 RIF order found that banning all paid prioritization chilled general innovation and network experimentation. These harms disproportionately fall on potential new entrants who are most likely to want to differentiate their service, perhaps by “zero-rating” popular services, but who are also least able to afford the cost of lawyers and consultations. It might also preclude practices that could have increased equity. For example, an agreement between an ISP and a content provider to guarantee a certain service quality for an application across varying network speeds would likely benefit subscribers to lower speeds most of all. ISPs have an incentive to provide the type of service consumers value, but insofar as limited competition in some areas of the country might prevent consumers from switching providers if they are unhappy with their ISP’s practices, the Commission should have expected those risks to have been greatest when competition was lowest. Since competition is increasing over time as more technologies emerge, the fact that ISPs have so far not required bright-line prohibitions to keep them from engaging in specifically harmful behaviors suggests that they are no more likely to in the future.[110]

We agree with several commenters who conclude that the proposed ban on paid prioritization may be at odds with the Commission’s desire to “preserve” and “advance” public safety. For example, the Free State Foundation says:

[T]he Notice does not even appear to directly permit any form of traffic prioritization for serving public safety purposes. And to the extent that such an omission is inadvertent, it might suggest the Commission has not adequately carried out its duty to consider the negative effects that a ban on paid prioritization can have on “promoting safety of life and property through the use of wire and radio communications.”[111]

NCTA points out that public safety during emergencies is one of the key instances in which prioritization is clearly beneficial:

If anything, retaining a light-touch regulatory regime for broadband would benefit public safety users by allowing ISPs to prioritize such critical traffic in times of emergency without fear of becoming subject to enforcement action for being “non-neutral.”[112]

A recurring theme throughout this rulemaking process is that the U.S. broadband industry is both competitive and dynamic. This vigorous competition forces providers to align their interests with those of their customers, as noted by CEI:

A bright line prohibition is also unneeded because the market will impose rationality on prioritization practices. If an ISP engaging in paid prioritization provides an inferior consumer experience, its customers are empowered to take their business elsewhere because most consumers have multiple options in ISPs. This is exactly how the market functions throughout the economy.[113]

The broadband market’s competitiveness and dynamism are demonstrated by two seemingly contradictory, but completely consistent statement from WISPA. First, it notes that anticompetitive paid prioritization can harm smaller providers:

WISPA is concerned that preferential traffic management techniques that are anti-competitive can be used to disadvantage providers that are unable to secure access to certain content or lack the leverage to obtain commercial terms afforded to broadband access providers with regional and national scope.[114]

At the same time, WISPA reports that there is no evidence of such anticompetitive conduct, and that if such conduct were found, it could be addressed under existing regulations:

These open internet principles can be preserved by maintaining the current light-touch regulatory approach. There is no market failure or evidence of blocking, throttling, paid prioritization or bad conduct from smaller providers that justifies saddling them with monopoly- based common carrier regulations.[115]

Comments in this proceeding reinforce our conclusions that, in nearly every case, paid prioritization benefits ISPs, consumers, and edge providers. To date, there has been no evidence of the anticompetitive use of paid prioritization or any harms to consumers or edge providers from the limited instances of above-board paid or affiliated prioritization arrangements. Thus, the Commission’s proposal to ban such arrangements is based on mere speculation, rather than “reasoned analysis.”

C. Blocking

The Commission proposes a “bright-line rule” prohibiting providers from “blocking lawful content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.”[116] The Commission “tentatively” concludes that providers “continue to have the incentive and ability to engage in practices that threaten Internet openness.”[117] But, just two paragraphs later in the NPRM, the Commission reports:

As far back as the Commission’s Internet Policy Statement in 2005, major providers have broadly accepted a no-blocking principle. Even after the repeal of the no-blocking rule, many providers continue to advertise a commitment to open Internet principles on their websites, which include commitments not to block traffic except in certain circumstances.[118]

At a conceptual level, issues like blocking and throttling could raise valid legal concerns when they are not done for valid network-management reasons. To date, however, there hasn’t even been a potential harm raised that would, if proven, not be remediable under existing antitrust law. Thus, arrogating more power to itself will do little to enhance the FCC’s ability to deter this conduct. the Providers’ behavior is already scrutinized under the Commission’s transparency rules, and any anticompetitive behavior can be pursued by antitrust enforcers.

But in practice, as the Commission notes, the providers have all committed to refrain from blocking and throttling unrelated to reasonable network management. This is akin to the old joke about clapping to keep away elephants.[119] We not aware of any comment in this matter that offers reliable evidence that any provider currently blocks lawful content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices. As noted above, the NPRM does not identify any examples of blocking in the last 15 years since the Madison River and Comcast peer-to-peer matters, and most providers have adopted explicit no-blocking policies.[120] The Commission concludes “this principle is so widely accepted, including by ISPs, we anticipate compliance costs will be minimal.”[121]

In comments on the 2015 Order, ICLE and TechFreedom noted that (1) many internet users are tech-savvy, (2) blocking is easily detectable by even those users who are not tech-savvy, and (3) blocking is widely unpopular. Therefore, providers likely have more disincentives to block content than incentives to do so:

There are already millions of tech-savvy Americans on the web, and the tools necessary to detect a blocking or serious degradation of service are widely available, so there is every reason to suspect that any future instances of such blocking will also be detected. If they are truly nefarious (i.e., the ISP is blocking a legal service/application that its customers are trying to access), then public outcry by the affected subscribers should likely be sufficient to convince the ISP to change its practices, rather than bear the brunt of public backlash, in hopes of pleasing its customers (and its investors).[122]

Even so, the Commission nonetheless also asserts that Title II regulation is necessary to ban a practice in which no one engages. Such assertions venture far away from “reasoned analysis” territory and deep into “arbitrary and capricious” territory.

D. Throttling

The Commission proposes to prohibit providers from “throttling lawful content, applications, services, and non-harmful devices.”[123] This is because the FCC “believe[s] that incentives for ISPs to degrade competitors’ content, applications, or devices remain”[124] even though the Commission also “believes” providers “have had a strong incentive to follow their voluntary commitments to maintain service consistent with certain conduct rules established in the 2015 Open Internet Order” during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.[125] TechFreedom concludes, “There is no real debate over these principles; everyone has agreed that blocking and throttling is such a bad idea that the marketplace has rejected it.”[126] Moreover, the Commission reports that the incidence and likelihood of provider throttling is so low that there will be “a minimal compliance burden” associated with the proposed ban:

Even after the repeal of the no-throttling rule, ISPs continue to advertise on their websites that they do not throttle traffic except in limited circumstances. As a result, we anticipate that prohibiting throttling of lawful Internet traffic will impose a minimal compliance burden on ISPs.[127]

Consistent with ICLE’s comments in this matter, 5G Americas reports that the change in the competitive broadband landscape, along with existing transparency rules, render blocking and throttling prohibitions unnecessary:

Blocking and throttling prohibitions are not needed, because internet business models require delivering the lawful content consumers want, at the speeds they expect. There have been no instances of mobile broadband providers engaging in discriminatory conduct since the 2017 RIF Order. This is because the internet ecosystem is dramatically different from when Title II regulation was first discussed in the early 2000’s. Today it is widely understood that content providers have more market power than ISPs. Reimposition of the 2015 rules is a proposal in search of a problem that doesn’t exist in the vastly differentiated marketplace of today.

In addition, the existing transparency rule is sufficient to protect against unlikely discriminatory conduct, making the general conduct rule, as well as the blocking and throttling prohibitions, unnecessary. It is notable that the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking makes no attempt to argue that since the 2017 RIF Order broadband providers have engaged in anticompetitive or non-transparent conduct that would justify regulating the entire industry as common carriers subject to ex ante oversight.[128]

The NPRM cites a study published in 2019, using data mostly from 2018, that “suggested that ISPs regularly throttle video content.”[129] We urge the Commission to be skeptical of relying on this study. As we report above, several commenters report that it has been “debunked.”[130] Moreover, we note in our comments that, to the extent the study found throttling, the authors concluded it was “not to the extent in which consumers would likely notice.”[131] In other words, the study does not reliably demonstrate “regular” throttling of content and any throttling detected was de minimis. CTIA’s comments provide a detailed summary of the study’s shortfalls:

The Notice also asserts that a study “suggested that ISPs regularly throttle video content,” but the Commission makes no findings and the Notice does not recognize the thorough rebuttal debunking the claims in the paper. The Li et al. Study purported to show throttling of video sites by wireless providers, but as CTIA noted at the time, the study used simulated traffic between artificial network end points and failed to account for basic network engineering, consumer preference, or how mobile content is distributed. Consumers, for example, have the ability to alter video resolution settings or sign up for steaming service plans that offer varying levels of resolution. Additionally, many video applications take actions themselves to automatically adjust to a network’s available bandwidth to improve the user experience. What the study identified, if found in a real-world setting, would be either reasonable network management, consumer choice, or data management practices used by content providers. allegation was therefore without merit and does not show harm to Internet openness.[132]

As with its proposed ban on blocking, the Commission asserts that Title II regulation is necessary to ban throttling—a practice in which no one engages. Such assertions venture far from “reasoned analysis” territory and deep into “arbitrary and capricious” territory.

IV. General Conduct Standard[133]

In this NPRM, the Commission seeks to revive the General Conduct Standard (also known as the Internet Conduct Standard) that was removed in the 2018 Order.[134] The General Conduct Standard is a catch-all rule that would allow the Commission to intervene when it finds that an ISP’s conduct generally threatened end users or content providers under some principle of net neutrality.[135] As “guidance,” the Commission proposes a non-exhaustive list of factors that could possibly (but not necessarily) be used to prove a violation.[136] The factors comprise an uncertain mashup of competition law, consumer-protection law, and First Amendment law and include 1) the effect on end-user control; 2) competitive effects; 3) effect on consumer protection; 4) effect on innovation, investment, or broadband deployment; 5) effects on free expression; 6) whether the conduct is application-agnostic; and 7) whether the conduct conforms to standard industry practices.[137]

The U.S Circuit Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejected US Telecom’s arguments that the 2015 General Conduct Rule should be invalidated.[138] Notwithstanding that decision, the Commission should be wary in moving forward with this provision. While the court may have found the General Conduct Standard was not vague in all its applications, the Court did not consider that, under State Farm, the Commission’s choice to implement such a far-reaching, ambiguous standard lacked a rational connection with FCC’s proffered facts.[139]

In the 2015 Order, the FCC claimed it had not created a novel, case-by-case standard, but rather that it was taking an approach similar to the “no unreasonable discrimination rule,” which was accompanied by four factors (end-user control, use-agnostic discrimination, standard practices, and transparency).[140] While the “no unreasonable discrimination rule” was grounded in Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, basing the General Conduct Standard in Sections 201 and 202 of the Communications Act (in addition to Section 706) enabled an unprecedented expansion of FCC authority over the internet’s physical infrastructure.[141] Then-Commissioner Ajit Pai noted at the time: