The Questionable Value of California’s Rate Intervenors

Executive Summary

In the 36 years since California voters moved to overhaul the state’s insurance regulatory system with Proposition 103, the state’s insurance market has struggled to keep pace with national trends and product innovations. As we have previously detailed, the rate-intervenor system created by Prop 103 has been among the most significant impediments to the efficient and effective functioning of the insurance market.

In practice, the intervenor process has proven both costly and time-consuming, with a five-year average filing delay of 236 days for homeowners insurance and 226 days for auto insurance. Such delays in rate filings make it more difficult for companies to change rates. Indeed, from 2018 to 2022, California ranked 49th in the number of homeowners-insurance rates filed, and 50th in the number of auto-insurance rates filed.

In addition, the state and the California Department of Insurance has for too long failed to exercise proper oversight of rate intervenors. The process has been dominated by a small handful of consumer groups—with the most significant participating organization founded by Prop 103’s author—that have rarely been called to task to prove that they are making the “substantial contribution” to the process required under the text of the law.

This issue brief details the form, function, and questionable value proposition of the rate-intervenor system and how it has served to render the Prop 103 rating system slow, imprecise, and inflexible. It also examines recent reform proposals to make the intervenor system more transparent and functional.

I. Prop 103 and the Intervenor System

California voters in November 1988 approved Proposition 103, the “Insurance Rate Reduction and Reform Act.” Authored by Harvey Rosenfield of the Santa Monica-based Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights (now known as Consumer Watchdog) and sponsored by Rosenfield’s organization Voter Revolt, Prop 103 carried narrowly with 51.1% yes votes to 48.9% against.[1]

Prop 103’s stated purpose was “to protect consumers from arbitrary insurance rates and practices, to encourage a competitive insurance marketplace.”[2] Rate increases and decreases became subject to the prior approval of the elected insurance commissioner, replacing the “open competition” system that had previously prevailed for 40 years under the McBride-Grunsky Insurance Regulatory Act of 1947, which required only that insurers submit rate manuals to the California Department of Insurance (CDI).[3]

Under Prop 103, public hearings are mandatory for personal lines increases of more than 6.9% and commercial lines increases of more than 14.9%, while others are at CDI’s discretion. The law created a role at these hearings for “public intervenors,” who are empowered to file objections on behalf of consumers, with fees to be paid by the applicant insurance company. Intervenors are granted petitions to intervene, as a matter of right, on any rate filing.

A. Intervenor Compensation and Transparency

Prop 103 authorizes intervenors who participate in rate filings to recover costs, expenses, and attorneys’ fees from insurers, who in turn can pass those costs on to consumers.[4] Individuals or organizations seeking to participate in the intervenor process must first apply for a finding of eligibility to seek compensation with the Office of the Public Advisor.[5] Applications for eligibility must include detailed corporate records, an accounting of consumer-protection activities, and disclosure of funding sources.

A finding of eligibility grants the individual or organization authority to petition to intervene in rate applications or investigatory or regulatory hearings involving property/casualty insurance, pending a ruling from CDI granting intervention. To obtain such a ruling, the intervenor must demonstrate that it can present relevant issues, evidence, or arguments that are separate and distinct from those already known by CDI. When a proceeding has completed, the intervenor submits a request for an award of compensation demonstrating that its participation yielded relevant, credible, and nonfrivolous information that the department would not otherwise have.[6] Compensation may not exceed “the prevailing rate for comparable services in the private sector in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Areas … for attorney advocates, non-attorney advocates, or experts with similar experience, skill and ability.”[7]

The intervenor process has proven both costly and time-consuming. According to CDI data, since 2003, intervenors have been paid $23,267,698.72, or just over $1 million annually, for successfully challenging 177 filings.[8] CDI currently publishes quantitative data concerning intervenor compensation and rate differentiation in intervenor proceedings.[9] But while this is helpful in conveying the scope of intervenor efforts, the data arguably fail to capture the value actually provided by intervenors in the ratemaking process.

A major reason that the intervenor system has been so disruptive is that CDI has not historically enforced Prop 103’s “sufficient” pleading requirements. For instance, intervenors can use generic criticisms of a carrier’s trend and loss development copied and pasted from previous petitions, without any requirement to plead application-specific arguments based upon the intervenor’s review of the data. The carrier instead bears the burden of proof to justify what’s in a filing, leaving the intervenor with no pleading burdens at all.

Since its inception, the intervenor program has been dominated by Consumer Watchdog, whose founder Harvey Rosenfield authored Prop 103. But the degree to which other organizations have taken part in the process has ebbed and flowed over time. As Daniel Schwarcz noted in 2012:

Until about 2004, a diverse range of organizations intervened in rulemaking and rate hearings, including organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Public Advocates Group, Consumer Union, Voter Revolt, and a handful of private citizens and attorneys. In recent years, however, a single organization – Consumer Watchdog (“CW”) – has become the sole significant user of the intervention process, particularly with respect to rate hearings. In fact, CW is the sole recipient of forty-two of the sixty-six awards made since 2003, and the only organization to receive any reimbursement since 2007. During that period, CW is also, with a single exception, the only party to receive compensation for intervening in rate applications.[10]

During the five-year period from 2007-2012 when Consumer Watchdog was the only organization to participate in the intervenor program, it collected more than $6.2 million in fees.[11] In July 2012, in response to concerns raised by lawmakers that Consumer Watchdog was dominating the process, then-Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones appointed enforcement attorney Ed Wu to serve as a public advisor to groups seeking to participate in the intervenor process.[12]

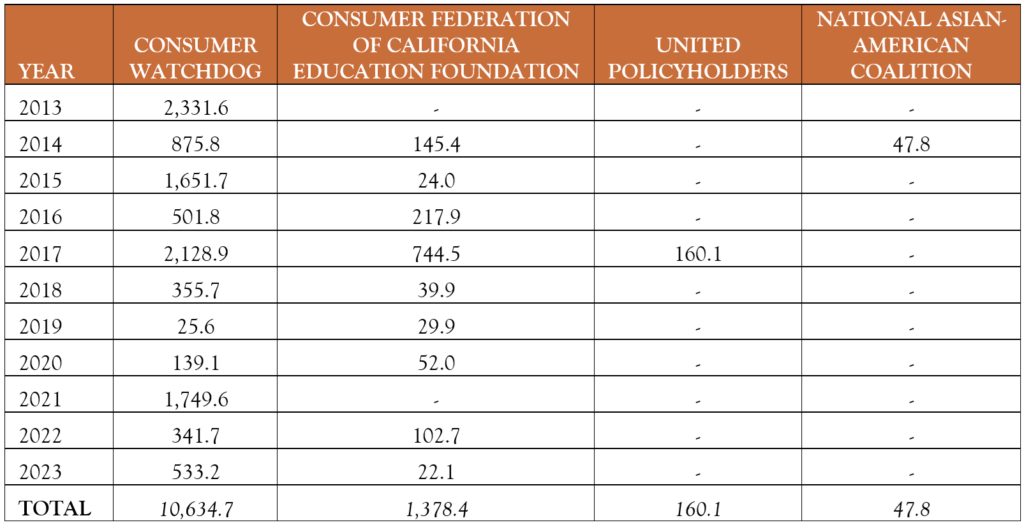

Between 2013 and today, CDI deemed four consumer organizations (Consumer Watchdog, the Consumer Federation of California Education Foundation, the National Asian-American Coalition, and United Policyholders) eligible for compensation as intervenors.[13] In addition, four individuals (Anthony Manzo, Andrea Stevenson, Donald P. Hilla, and John Metz) and a trio of plaintiffs in a lawsuit against Farmers Insurance (Roger Harris, Duane Brown, and Brian Lindsey) have also been found eligible for compensation as rate intervenors;[14] to date, however, none of the individual intervenors has been awarded compensation by CDI.

Table 1 details annual compensation totals for the four eligible consumer organizations from 2013 to 2023.

Table I: Total Compensation Awarded to Intervenors, 2013-2023 ($000)

SOURCE: California Department of Insurance[15]

As is obvious from Table 1, Consumer Watchdog remains by far the most active intervenor, taking 87% of the $12.2 million in compensation awarded over the past decade.

B. Rate Delays and the Death of the ‘Deemer’

The intervenor process has also contributed to California having the second-most time-consuming rate-approval system in the country, behind only Colorado, with a five-year average filing delay of 236 days for homeowners insurance and 226 days for auto insurance.[16]

As originally presented to California voters, Prop 103 proposed that insurers’ rate filings would be deemed accepted if no action were taken by the CDI for 60 or 180 days.[17] Indeed, Prop 103 included this “deemer” provision because a reasonable speed-to-market for insurance products also protects consumers.

The law’s deemer provision has been effectively rendered moot in practice because, as a matter of course, the CDI requests that firms waive the deemer. If the deemer is not waived, the CDI has two options: approve the rate or issue a formal notice of hearing on the rate proposal. Because the CDI is unable to complete timely review of filings within the deemer period, it always elects to move to a rate hearing. In effect, CDI has turned every rate filing without a deemer waiver into an “extraordinary circumstance.”[18]

In practice, it has proven exceedingly challenging for petitioners to navigate the manner in which rate hearings—the nominal guarantors of due process—are conducted. The administrative law judges (ALJs) that oversee these proceedings are housed within the CDI. The hearings themselves take a broad view of relevance that drive up the cost of participation. Upon ALJ resolution, the commissioner can accept, reject, or modify the ALJ’s finding. There is little practical upside for an insurer to move to a hearing against the CDI.

Insurers are therefore faced with a starkly practical choice. One option is to waive their right to timely review of rates, and hope that they gain approval in, on average, six months. The alternative is to move to a formal hearing and reconcile themselves with the fact that approval, if forthcoming, will take at least a year. The system of due process originally contemplated by Prop 103 simply bears no relationship with the system as it operates today.

II. Proposed Reforms

In recent months, an accelerating insurance-availability crisis and the announced exits of several of the state’s largest homeowners insurers have forced California leaders to rethink the ossified Prop 103 system. The proximate cause of the crisis has primarily been historically costly wildfires, and Prop 103’s inflexibility to allow insurers to adjust rates appropriately. In 2017 and 2018 alone, for example, California homeowners insurers posted a combined underwriting loss of $20 billion, more than double the total combined underwriting profit of $10 billion that the state’s homeowners insurers had generated from 1991 to 2016.[19]

While the highest-profile of the proposed reforms would address longstanding regulatory interpretations of Prop 103 that barred insurers from considering the cost of reinsurance in their rate filings or from using the output of catastrophe models to craft forward-looking loss estimates, policymakers have also turned their attention to ways to reform the intervenor process.

A. Expedited Rate Filings

In September 2023, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced an emergency executive order to stabilize the state’s rapidly deteriorating market for property insurance. The order directed Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara to take “swift regulatory action to strengthen and stabilize California’s marketplace,” including by implementing changes to “[i]mprove the efficiency, speed, and transparency of the rate approval process.”[20]

For his part, Commissioner Lara announced an emergency response plan that called for:

Improving rate filing procedures and timelines by enforcing the requirement for insurance companies to submit a complete rate filing, hiring additional Department staff to review rate applications and inform regulatory changes, and enacting intervenor reform to increase transparency and public participation in the process …[21]

In May 2024, Newsom followed up with a “trailer” bill attached to the state’s 2024-2025 budget that would require the California Department of Insurance to respond to rate requests from insurers within 120 days and, if an insurer requests an average rate hike of more than 7%, to provide insurers with a suggested rate within that same time period.[22]

In essence, the proposal would amount to restoring the “dead letter” deemer provisions of Prop 103. Such reforms are crucial, as California’s sluggish regulatory system appears to be getting slower over time. The annual average number of days between filing and resolution of rate changes for homeowners insurance in California was 157 days from 2013 to 2019; from 2020 to 2022, the average delay increased to 293 days.[23]

These reforms are welcome. CDI could bolster them by committing, as a matter of administrative policy, to exercise its discretion not to convene public hearings on filed rate changes of less than 7% for personal lines or 15% for commercial lines. Such hearings add expense, administrative burden, and delays to very modest changes in product offerings. In particular, if a filing is made on the basis of least-inflationary or least-aggressive loss-development assumptions, CDI should undertake a light-touch review focused on rate sufficiency to expedite the approval process. This approach would have the benefit of increasing both the predictability and speed of the ratemaking process.

B. Improved Intervenor Transparency

Questions long have been raised about the degree to which Consumer Watchdog has abided regulatory mandates that intervenors’ compensation and attorney and advisor fees are reasonable. Indeed, circa 2012, the group inspired a website called ConsumerWatchdogWatch.com, launched by a former chief of staff to then-Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez and former press secretary to then-Gov. Gray Davis, that accused it of being “a ‘pay to play’ organization that generates millions of dollars for itself in fundraising schemes without revealing its special interest donors.”[24]

Of particular interest is the degree to which a significant portion of the 501(c)3 organization’s revenues flow to just a handful of contractors. According to the organization’s Form 990 filings with the Internal Revenue Service, over the 15 years from 2008 to 2022, Consumer Watch paid Rosenfield $6.8 million for legal and professional services, and an additional $3.9 million to Freehold, N.J.-based actuarial firm AIS Risk Consultants Inc.[25] Over that same period, Consumer Watchdog President Jamie Court earned $4.7 million.[26] Together, Rosenfield, Court, and AIS took about 28% of the $54 million in total revenue the organization received over those 15 years.[27]

The department and its ALJs have at times questioned the quality of Consumer Watchdog’s contributions to the process. As Schwarcz has noted:

CW’s scattershot approach has its costs. ALJs often regard its positions with skepticism – and occasionally, with hostility. For example, one ALJ dismissed the organization’s actuarial work as being “without merit,” saying that its arguments were “deficient and not credible.” Another said that CW’s testimony “at the least, is careless, and may be dodgier than that.”[28]

The organization had nonetheless enjoyed a lengthy streak of being renewed for eligibility to participate as a rate intervenor. In October 2023, however, Commissioner Lara denied a Consumer Watchdog petition to intervene in a rate filing by Liberty Insurance Corp., citing that the organization had submitted a “conclusory” finding that Liberty’s filed rate indication was inflationary and that the group “failed to meet its burden of proof with respect to the actuarial soundness of the selected trend factors and trend data period used.”[29] Moreover, Lara contended on separate contentions in the filing that Consumer Watchdog did “not plead any specific issue, but instead, holds open the possibility that an issue might arise in the future.”[30]

That denial would not be the last. In June 2024, Lara denied a pair of Consumer Watchdog petitions to intervene—in filings by USAA and State Farm in which the group sought $245,175 and $227,175 of compensation, respectively—with the commissioner declaring in both orders that the group’s proposed budget was “not supported by any documentation, exhibits, an attestation or even a mere statement that the hourly rates it contained did not exceed market rates.”[31]

Also in June, Lara delayed approval of Consumer Watchdog’s eligibility petition to continue to serve as an intervenor, on grounds that he could not yet determine whether its submission of documentation about its members, board of directors, and funding sources, and its required showing that it “represents the interests of consumers” were complete.[32] Given the delay, Consumer Watchdog’s existing eligibility determination expired July 12, 2024. Lara noted in his order that he would issue a decision in the matter no earlier than Aug. 2, 2024.[33]

The department’s recent posture of enhanced skepticism toward the value provided by rate intervenors has not been limited to Consumer Watchdog. In April 2024, the department initially denied a petition to intervene filed by the Consumer Federation of California Education Foundation on grounds that it cited “no specific issues to be raised or positions to be taken on any issue” in a proceeding concerning the department’s proposed regulatory action regarding complete property/casualty rate applications.[34]

These recent developments raise hope that the department might exercise its discretion to reduce and sometimes reject fee submissions due to the lack of significant or substantial contribution. The department has long rubber-stamped fee requests, thereby creating incentives for unnecessary and costly delays in reviews and in actuarially justified rate increases.

But while this recent posture is to be welcomed, the concern is that it could be limited to ad hoc interventions that fall by the wayside when the current crisis abates. More lasting change in regulatory procedure is essential if California is to better understand the value that intervenors offer, and to ensure that intervenor engagement is both efficient and effective.

One way to change the system for the better would be to find that a carrier’s compliance with the complete-rate-application requirements shifts the burden to the intervenor for why an actuarial selection is wrong. That would require the intervenor to actually perform analysis in the first 45 days and present their data and calculations. The requirements to demonstrate a “substantial contribution” should also be tightened. To be eligible for compensation, petitioners should be required to show nonduplicative contributions or novel arguments that the CDI wouldn’t otherwise make. Where the intervenor merely repeats the same critiques as CDI, it should not trigger payments.

Another useful change would be to return to the pre-2006 definition of when a “proceeding” begins. Under the original iteration of intervenor regulations, it commenced upon appointment of an ALJ for an adversarial proceeding. Intervenors were not permitted to participate in pre-hearing discussions between an insurer and the CDI; they could only earn compensation for disputes that proceeded to a hearing. Returning to that original definition would reduce disruptions that hold up filings.

Similarly, CDI and the Legislature should examine how the definition of “market rate” is applied to intervenor compensation.[35] The state code currently requires that compensation may not exceed “the prevailing rate for comparable services in the private sector in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Areas … for attorney advocates, non-attorney advocates, or experts with similar experience, skill and ability.” But given that the Santa Monica-based Consumer Watchdog has long been effectively the only provider of “comparable services” in this space, the question must be raised whether it is effectively setting the very billing benchmark against which its own compensation requests are judged. Moreover, given that Consumer Watchdog’s single-largest outside contractor is based in New Jersey, CDI should interrogate whether the out-of-state rates AIS charges Consumer Watchdog for its actuarial services actually comport with prevailing in-state rates.

The qualitative contributions made by intervenors are also obscured by the fact that none of their filings appear publicly on the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ (NAIC) System For Electronic Rates and Forms Filing (SERFF). Not only is this an aberration relative to other proceedings before the CDI, but there could be significant value in getting greater transparency from the intervenor process, given the delays and direct costs related to intervention.

The CDI has in the past year established a webpage that posts some information on intervenors’ filings and participation, but this requires observers to perform manual checks, rather than the far simpler option of checking SERFF. Allowing the Legislature and the public to assess the substantive value of intervenor contributions would ensure not only substantial due-process protections for filing entities, but would also guarantee that consumers are afforded a high level of representation in proceedings. For instance, such transparency would function as a guarantor that intervenor filings are not otherwise duplicative of CDI efforts. It would therefore allow the public to assess whether intervenors are diligent in efforts putatively made on their behalf.

[1] Steve Geissinger, Californians Approve Auto Insurance Cuts, Insurer Files Lawsuit, Associated Press (Nov. 9, 1988).

[2] Text of Proposition 103, Consumer Watchdog (Jan. 1, 2008), https://consumerwatchdog.org/insurance/text-proposition-103.

[3] Cal. Ins. Code §1850-1860.3.

[4] Cal. Ins. Code §1861.01-1861.16.

[5] Cal. Code of Regulations, Title 10, Ch. 5, §2623.2.

[6] Cal. Code of Regulations, Title 10, Ch. 5, §2623.5.

[7] Cal. Code of Regulations, Title 10, Ch. 5, Art. 13, §2661.1(b).

[8] Data are drawn from Informational Report on the CDI Intervenor Program, California Department of Insurance, available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/report-on-intervenor-program.cfm (last visited Jul. 17, 2024).

[9] Informational Report on the CDI Intervenor Program, California Department of Insurance, https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/report-on-intervenor-program.cfm (last accessed Aug. 16, 2023)

[10] Daniel Schwarcz, Preventing Capture Through Consumer Empowerment Programs: Some Evidence from Insurance Regulation, Minnesota Legal Studies Research Paper No. 12-06 (Jan. 11, 2012).

[11] Don Jergler, California Legislator Calls for Hearing on Intervenor Fees, Insurance Journal (May 17, 2012), https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/west/2012/05/17/247939.htm#.

[12] Jones Names New Public Advisor To Would be Intervenors, Insurance Journal (Jul. 18, 2012), https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/west/2012/07/18/256128.htm#.

[13] Requests for and Findings of Eligibility to Seek Compensation, Received Since January 1, 2013, California Department of Insurance, available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/Requests-for-and-Findings-of-Eligibility-7-11-24.pdf (last updated Jul. 11, 2024)

[14] Id.

[15] Total Compensation Awarded to Intervenor, California Department of Insurance, available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/Total-Compensation-2013-2023_7-16-24.pdf (last updated Jul. 16, 2024).

[16] Lawrence Powell, R.J. Lehmann, & Ian Adams, Rethinking Prop 103’s Approach to Insurance Regulation, Connecticut Insurance Law Journal (forthcoming), available at https://laweconcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Rethinking-Prop-103s-Approach-to-Insurance-Regulation-2.pdf.

[17] Cal. Ins. Code §1861.05.

[18] Cal. Ins. Code §1861.065(d).

[19] Eric J. Xu, Cody Webb, & David D. Evans, Wildfire Catastrophe Models Could Spark the Change California Needs, Milliman (Oct. 2019), available at https://fr.milliman.com/-/media/milliman/importedfiles/uploadedfiles/wildfire_catastrophe_models_could_spark_the_changes_california_needs.ashx.

[20] Press Release, Governor Newsom Signs Executive Order to Strengthen Property Insurance Market, Office of Gov. Gavin Newsom (Sep. 21, 2023), https://www.gov.ca.gov/2023/09/21/governor-newsom-signs-executive-order-to-strengthen-property-insurance-market.

[21] Press Release, Commissioner Lara Announces Sustainable Insurance Strategy to Improve State’s Market Conditions for Consumers, California Department of Insurance (Sep. 21, 2023), https://www.insurance.ca.gov/0400-news/0100-press-releases/2023/release051-2023.cfm.

[22] 2024-25 Budget – Streamlined Review of Pending Insurance Filings, California Department of Finance, available at https://esd.dof.ca.gov/trailer-bill/public/trailerBill/pdf/1140 (last updated May 28, 2024).

[23] Powell, Lehmann, & Adams, supra note 16.

[24] Press Release, ConsumerWatchdogWatch.com Launched to Expose ConsumerWatchdog.org, ConsumerWatchdogWatch.com (Feb. 8, 2012), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/consumerwatchdogwatchcom-launched-to-expose-consumerwatchdogorg-138926074.html.

[25] Consumer Watch OMB No. 1545-0047, Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax (2008-2022).

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Schwarcz, supra note 10 (citations omitted).

[29] Ricardo Lara, Order Denying Consumer Watchdog’s Petition to Intervene with Leave to Amend, California Department of Insurance (Oct. 3, 2023), available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/Order-Denying-CW-Petition-to-Intervene_Liberty-Insurance-Petition_10-2023.pdf.

[30] Id.

[31] Ricardo Lara, Amended Order Denying Consumer Watchdog’s Petition to Intervene, California Department of Insurance (Jun. 25, 2024), available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/AMENDED-ORDER-DENYING-CW-S-PETITION-TO-INTERVENE-RE-SFMAIC-RULE-FILE-NO-24-788.pdf; Ricardo Lara, Order Denying Consumer Watchdog’s Petition to Intervene, California Department of Insurance (Jun. 18, 2024), available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/Order-Denying-CW-Petition-to-Intervene-in-United-Services-Auto-Association-Garrison-and-USAA-Casualty-24-722-723-744.pdf.

[32] Ricardo Lara, Order Concerning Consumer Watchdog’s Request for Finding of Eligibility to Seek Compensation, California Department of Insurance (Jun. 19, 2024), available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/ORDER-CONCERNING-CW-REQUEST-FOR-FINDING-OF-ELIGIBILITY-TO-SEEK-COMPENSATION-IE-2024-0002.pdf.

[33] Id.

[34] Ricardo Lara, Order Denying Consumer Federation of California Education Foundation’s Petition to Participate in the Proposed Regulatory Action Regarding Complete Property and Casualty Rate Applications, California Department of Insurance (Apr. 10, 2024), available at https://www.insurance.ca.gov/01-consumers/150-other-prog/01-intervenor/upload/ORDER-DENYING-CFCEF-S-PETITION-TO-PARTICIPATE-IN-THE-PROPOSED-REGULATORY-ACTION-REG-2019-00025.pdf.

[35] Supra note 7.