The Consequences of Caps on Cross-Border Payment Fees in Costa Rica

Executive Summary

Under the auspices of Legislative Decree 9831, the Central Bank of Costa Rica (BCCR) has set maximum fees for acquiring and issuing banks in payment-card markets, with maximum acquisition fees (MDR) and interchange fees (IRF). Different fees were set for domestic transactions (i.e., those made using locally issued cards) and for cross-border transactions (i.e., those made using foreign-issued cards).

In November 2022, BCCR issued a proposal to retain the cross-border MDR cap at 2.5% and either to leave the cap on cross-border IRF unchanged at 2%, or to lower it to 1.25%. In the same document, BCCR proposed that the MDR for domestically issued cards would be capped at 2% and the IRF capped at 1.5%.

IRF for cross-border transactions typically are significantly higher than those for domestic transactions, primarily because cross-border transactions carry much higher risk of fraud. If BCCR caps cross-border interchange fees at the lower level it has proposed, foreign issuers are likely to respond by de-risking payment requests from acquirers in Costa Rica. This could take various forms, including rejecting payments from certain merchants, or simply increasing rejections rates across the board. Whatever approach, or mix of approaches, is taken, it is likely to cause problems both for merchants in Costa Rica and for their customers.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, roughly 6.25% of Costa Rica’s gross domestic product (GDP) came from tourism, with a significant proportion of those tourist dollars spent using payment cards. Indeed, in 2021, even without a full resumption of pre-COVID rates of tourism, approximately 16% of credit-card payments in Costa Rica were cross-border. If tourists find that they are unable to make reservations at hotels in Costa Rica using their credit or debit cards because the payment is rejected by their issuer, they may well choose an alternative destination for their trip. Meanwhile, if tourists in Costa Rica are unable to pay for goods and services using their credit and debit cards, many will simply not make those payments. This could have a substantial negative effect on Costa Rica’s tourism and business-travel industries.

Introduction

Costa Rica Legislative Decree No. 9831—issued March 24, 2020—created a mandate to regulate acquisition fees (commonly known as the “merchant discount rate,” or MDR) and interchange reimbursement fees (IRF) charged by service providers on “the processing of transactions that use payment devices and the operation of the card system.”[1] The legislation’s stated objective was “to promote its efficiency and security, and guarantee the lowest possible cost for affiliates.”

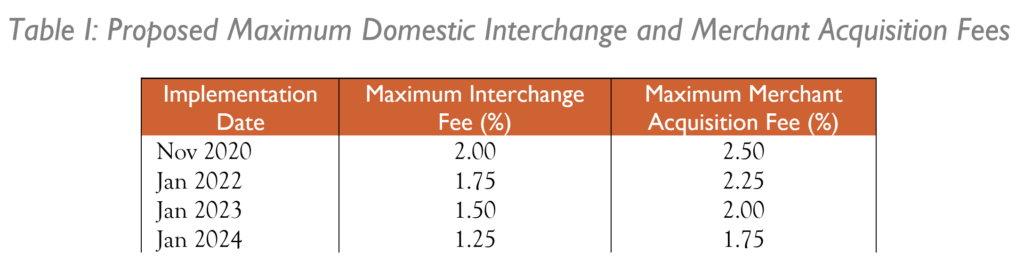

Implementation was delegated to the Central Bank of Costa Rica (BCCR), which was tasked with responsibility to issue regulations and monitor compliance; ensure that the rule is “in the public interest”; and guarantee that fees charged to “affiliates” (i.e., merchants) are “the lowest possible … following international best practices.” Beginning Nov. 24, 2020, BCCR set the maximum IRF for domestic cards at 2.00% and the maximum MDR at 2.50%. These fell to 1.75% and 2.25%, respectively, in an updated regulation published in January 2022, and to 1.5% and 2% in February 2023.

In a study published in May 2022, we reviewed the available evidence regarding interchange fees and argued that it would be contrary to international best practices for Costa Rica to cap acquisition fees and interchange fees.[2] In particular, we raised specific concerns regarding the likely harmful effects of capping fees on cross-border transactions, owing to the higher risks and other costs associated with such transactions.

BCCR developed a technical study that considered the effects of different levels of caps on fees for both domestic and cross-border payment-card transactions and, in November 2022, issued a proposal to retain the cross-border MDR cap at 2.5% and either (1) leave the cap on cross-border IRF unchanged at 2%, or (2) lower the IRF cap for cross-border transactions to 1.25%.

If BCCR leaves the cross-border MDR cap unchanged but reduces the cross-border IRF cap to 1.25%, it might, in principle, appear to solve the immediate problem faced by acquiring banks. It would, however, create new problems for those banks, their customers, and the wider economy. It will also put Costa Rica in the unenviable position of being the only country in the world with a cross-border interchange fee that is below the domestic interchange fee.

This brief considers the international experience with cross-border payment-card transactions, with a focus on issues related to fraud, as well as the negative implications of imposing price caps. It begins with a brief discussion of the economics of interchange fees. Section II describes Costa Rica’s price controls on merchant acquisition and interchange fees. Section III discusses fraud and other costs associated with cross-border and card-not-present transactions. Section IV describes ways in which payment-card networks address issues related to fraud. And Section v assesses the likely implications for Costa Rica of price caps on cross-border interchange fees.

I. The Economics of Interchange Fees

Payment systems are two-sided markets, with consumers on one side and merchants on the other; the payment network acts as a platform that facilitates interactions between the two sides.7F[3] For such a system to be successful, both merchants and consumers must perceive it as beneficial. If too few merchants accept a particular form of payment, consumers will have little reason to obtain it and issuers will have little incentive to issue it. Likewise, if too few consumers possess a form of payment, merchants will have little reason to accept it.

In any two-sided market, platform operators seek to encourage participation on each side of the market in ways that maximize the joint net benefits of the network to all participants—and to allocate system costs accordingly.8F[4] Among the means they employ to achieve this balance is by setting prices charged, respectively, to participants on each side of the market.9F[5] In the case of payments, if the platform operator sets the price too high for some consumers, they will be unwilling to use the platform; similarly, if the operator sets the price too high for some merchants, they will not be willing to use the platform.

In general, the costs of operating a platform will tend to fall on the party who is least sensitive to such costs (i.e., the party with the lower price elasticity). In the case of payment cards, that party is the merchant.13F[6] Merchants often pay, through transaction fees, not only all the costs of accessing the network, but also effectively subsidize participation by consumers—e.g., through cashback and other rewards programs, insurance, fraud protection, and other cardholder benefits that serve as incentives to card usage.

Merchants are willing to do this because they receive significant benefits from the use of payment cards, including: ticket lift (i.e., higher spending, due to the fact that consumers are not constrained by the cash in their pockets or, in the case of credit cards, the amount of cash currently in their bank accounts), guaranteed payment, reduced cash-management costs, and faster checkout times.

II. Costa Rica’s Price Controls on Payment Card Fees

Article 14 of Legislative Decree 9831 requires the BCCR to undertake “ordinary reviews” of the price controls on MDR and IRF at least once annually. Its first such review, published in November 2021, set a timetable for maximum domestic-acquisition and interchange fees (see table below) and set maximum cross-border MDR at 2.5% and IRF at 2%.[7]

SOURCE: Banco Central de Costa Rica[8]

BCCR subsequently established a task force to develop proposals for setting payment-card fees. On Nov. 2, 2022, BCCR published the task force’s recommendations, which included, inter alia, the following:[9]

- Use international comparisons of IRFs and MDRs “as the best technical tool currently available to the BCCR to ensure the lowest possible cost for affiliates, in accordance with Legislative Decree 9831.”

- Maintain the differentiation of the ceilings on IRF and MDR between local and cross-border payment transactions, in accordance with Article 4 of Legislative Decree 9831, “as this leads to the proper functioning, efficiency and security of the Costa Rican payment system and the lowest cost for affiliates.”

- For 2023, set maximum fees for local payment transactions at 1.50% for IRF and 2.00% for MDR. This is in line with the proposal made in 2021.

- Maintain the cap of 2.50% on cross-border MDR, “since the information available in the international comparison does not allow modifications to be made to the limit established since 2020.”

- Propose two alternative options regarding the maximum cross-border IRF:

- Option 1: maintain the current maximum, e., 2.00%; or

- Option 2: reduce the maximum to 1.25%.

The BCCR offers various putative justifications for these proposed caps. For example, it notes that Option 2 would result in a maximum cross-border IRF that is midway between “the minimum cross-border IRF established by Mastercard and Visa card brands for the United States and Canada, as well as Visa for Australia in the case of non-Asia Pacific issuers” (i.e., 1.00%) and the IRF “agreed by Mastercard and Visa card brands for card-not-present payments in the EEA” (i.e., 1.50%).

Such justifications, however, are fundamentally inconsistent with the economics of two-sided markets. The current and proposed price caps thus represent essentially arbitrary interventions. By focusing narrowly on the costs incurred by merchants through IRFs and MDRs, BCCR fails to account adequately for the offsetting benefits that accrue to consumers and merchants—and the costs to provide those benefits.

Legislative Decree 9831 does, however, permit BCCR to take into consideration “[a]ny other element that reasonably allows the Central Bank of Costa Rica to guarantee the efficiency and security of the card systems.”[10] As discussed below, one such element that should be considered by BCCR is the potential effect of regulating international IRFs on merchants in Costa Rica, especially those catering to tourists and business travelers, and the wider effects on the economy.

III. Fraud Risks Associated with Cross-Border Payments

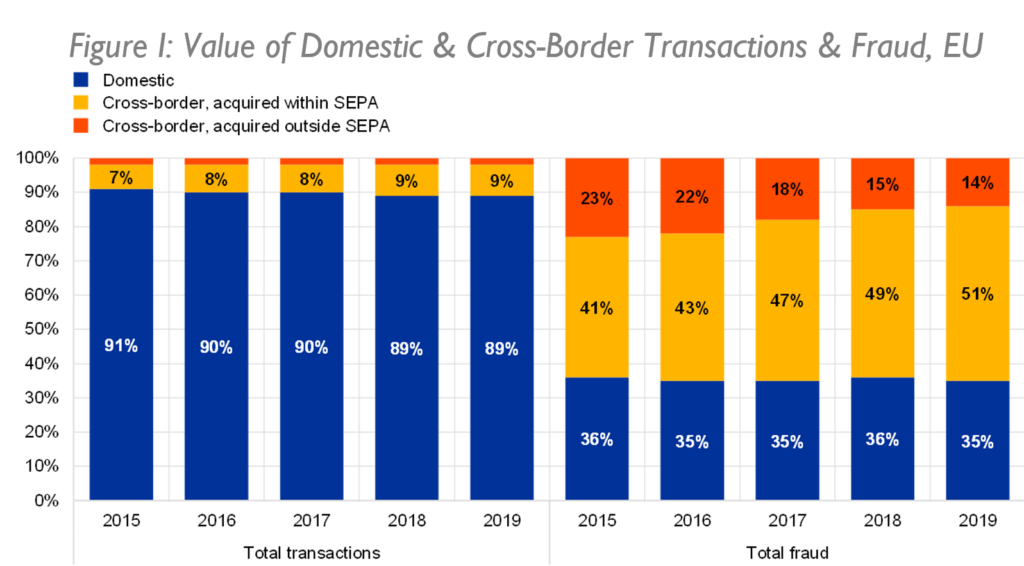

In comparison to domestic payments, cross-border payments entail significantly higher risks of fraud, as be seen by looking at the incidence of payments fraud in the European Union (EU). Data from the European Central Bank (ECB) show unambiguously that the rates of fraud on cross-border transactions—both between EU member states and from outside the EU—is much higher than fraud on domestic transactions. In its 2021 Report on Card Fraud, the ECB found that, between 2015 and 2019, cross-border transactions represented only 10% of transactions by value but 65% of all fraud by value, as can be seen in Figure I.[11] Thus, in value terms, cross-border fraud represents a risk more than six times greater than domestic fraud.

SOURCE: European Central Bank[12]

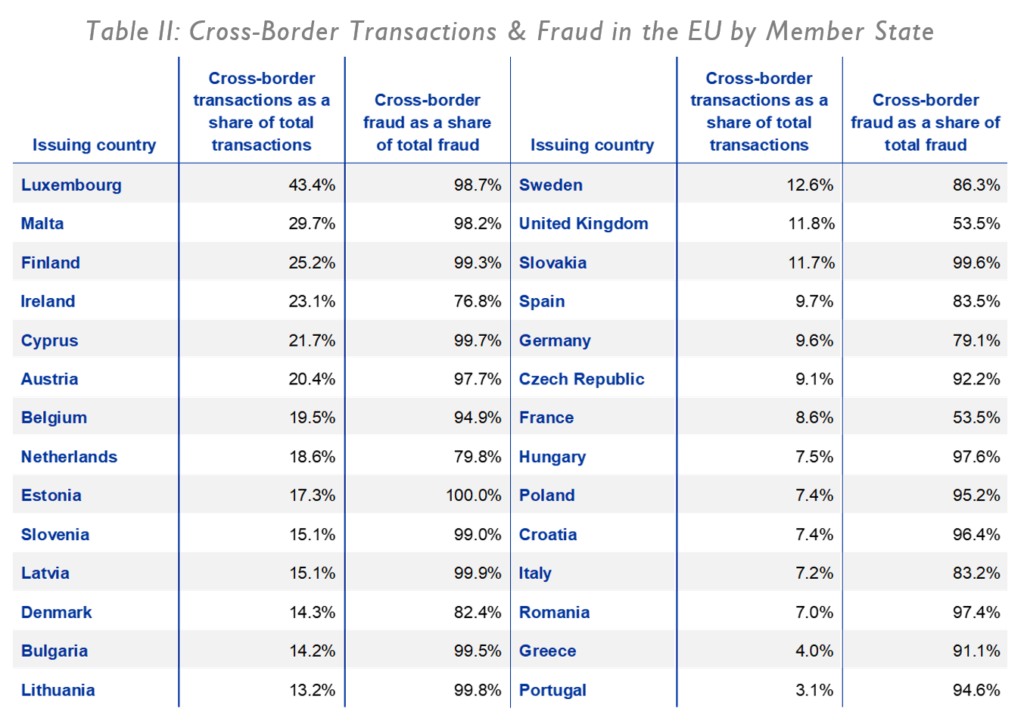

For most EU member states, the situation is even more dramatic, with cross-border fraud representing more than 90% of all card fraud, as can be seen in Table II.

SOURCE: European Central Bank[13]

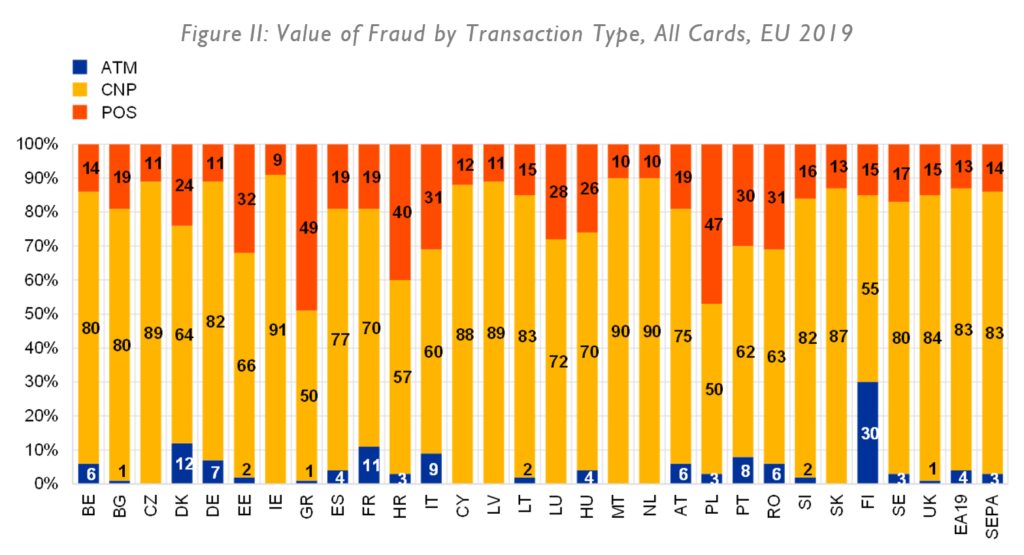

Looking at the types of transaction involved in card fraud, the vast majority (83%) are card-not-present (CNP) fraud, as can be seen in Figure II.

SOURCE: European Central Bank[14]

While these data relate to payments fraud in the EU, they are likely indicative of broader international trends. As such, they suggest that cross-border fraud in general and CNP cross-border fraud in particular is a far more significant problem than domestic fraud of all kinds.

IV. How Card Networks Address Payment-Card Fraud

Card networks have developed numerous processes and technologies to address payment-card fraud, including the following.

Zero liability protection for cardholders. Card networks’ standard terms and conditions include clauses requiring issuers to protect personal cardholders from unauthorized transactions (subject to certain conditions, such as that cardholders report such transactions promptly to the card issuer).[15] This protection is an important benefit to cardholders, who otherwise might be wary of using their cards, especially for online transactions or in foreign countries.

Liability protection for merchants. Just as cardholders are protected from liability for unauthorized transactions, so too are merchants. Issuers are, by default, liable for unauthorized transactions. This is an important benefit to merchants, who might otherwise be reluctant to accept card-based payments.

Chargebacks. The above liability protections apply only to unauthorized transactions. Where a cardholder has authorized a payment, they will be liable. Meanwhile, if a merchant has processed a payment without obtaining the necessary authorization, and where that payment has been disputed by the cardholder, the issuer may initiate a “chargeback”: effectively reversing the payment.

Authorization, verification, and fraud monitoring. To complement the system of liability protection and chargebacks, payment networks have developed increasingly sophisticated and effective systems for transaction authorization and fraud monitoring, including:

- Tokenization—which underpins EMV (Europay, Mastercard, and Visa) chips, contactless cards, and smartphone-based payments—uses encrypted data to enable authorization without sharing personal account numbers;

- Machine-learning-based transaction monitoring, which creates a dynamic model of each cardholder’s transactions and flags as potentially fraudulent those payments that do not fit the model; and

- Contingent multifactor authentication, whereby transactions flagged as potentially fraudulent result in the cardholder being asked for secondary authentication.

These systems reduce the incidence of fraud and thereby reduce the liability of card issuers. For example, in 2015, payment networks changed the liability rules for U.S. merchants to encourage adoption of EMV cards. Estimates by Visa suggest that merchants that subsequently adopted EMV-compliant point-of-sale (POS) machines experienced an 87.5% reduction in fraud.[16] Nonetheless, as is clear from Section III, fraud remains a problem, especially for cross-border and CNP transactions.

The liability rules summarized above mean that the cost of fraud falls disproportionately on card issuers. In 2020, issuers bore nearly two-thirds of all card fraud losses worldwide.[17] The equitable and economically efficient solution is for issuers to charge higher fees for transactions that are more likely to be fraudulent.

In some cases, it may make sense to pass on some or all of these costs to consumers. In the case of cross-border transactions, some issuers do this by charging foreign-transaction fees on some cards.[18] Such fees can, however, discourage consumers from using their cards, so it may be preferable for merchants to pay higher fees instead. Thus, cards aimed at international travelers typically offer cardholders “no foreign-transaction fee” as a benefit. These cards instead charge a higher interchange fee for foreign transactions. Holders of such premium cards typically spend more, thereby benefiting the merchants (who pay slightly higher fees, if they are not on a blended rate).

V. Possible Responses to Caps on Cross-Border Interchange Fees

As noted in Section II, the BCCR Task Force made two alternative proposals with respect to cross-border IRFs. The first would leave the current cap unchanged at 2.00%, while the second would reduce the cap to 1.25%.

Even the current cap is lower than the standard IRF charged for many credit cards that offer no foreign-transaction fee. Payments made using such cards in Costa Rica are thus effectively subsidized by merchants in other jurisdictions that do not impose such caps.

At the lower proposed rate, foreign issuers will receive a lower IRF than domestic-card issuers. Given the much higher fraud rate on cross-border payments, this is likely to cause significant problems, especially for premium cards that offer cardholders “no foreign-transaction fee” as well as other benefits, such as vehicle insurance, purchase-protection insurance, and rewards. The IRF revenue simply will not be sufficient to cover these benefits. As such, to reduce fraud, payments using such cards will be subject to greater scrutiny and many may well simply be rejected.

This is a problem not only for the cardholders, who will be frustrated when attempting to make purchases. It is also a problem for Costa Rica’s tourism and business-travel sectors. Consider what might happen when a prospective visitor attempts to book a room at a resort such as Tortuga Lodge, which takes bookings directly on its website and processes payments through its acquirer in Costa Rica.[19] The prospective visitor first tries their World Elite Mastercard and finds that it is rejected; they then try their Visa Infinite card and again find that the payment is rejected. Frustrated but undaunted, they instead decide to book rooms at Tortuga Lodge on Expedia.com, which uses a U.S. acquirer; this time, they have no problem making and paying for the booking, albeit at a higher price than was offered directly by the hotel. When they arrive in Costa Rica, however, they find that, once again, their cards are repeatedly rejected when they attempt to make purchases, whether it be at restaurants, tour agencies, or even an art gallery where they had hoped to buy a beautiful piece of local artwork.

The above scenario might already be happening, because the standard IRF for such transactions on the cards mentioned is higher than the current capped rate of 2.00%.[20] At the alternative lower proposed rate of 1.25%, rejections are a near certainty for at least some travelers. Worse, some prospective travelers who are looking for a more bespoke offering and want to book directly with the hotel are likely to abandon their plans to travel to Costa Rica at all and choose a different destination where they do not encounter such difficulties.

Ironically, prospective visitors who have standard debit or credit cards that charge foreign-transaction fees are much less likely to have their payments rejected.

Some other payment methods are not covered by the caps on MDRs and IRFs: specifically, wire transfers and other bank-to-bank transfers that do not involve the use of payment-card networks. Most likely, there will be a shift toward the use of such payment methods, as a result both of individuals paying directly through such transfers and an increase in payments from overseas agencies. In general, such alternative payment methods involve greater counterparty risk than payments made using cards due to their greater finality, which means it is more difficult to reverse a payment once made, and the lack of purchase insurance. To the extent that visitors to Costa Rica are limited to wire and bank transfers, as a result of their payment cards being declined, they are likely to reduce their spending.

These anecdotes and observations suggest a number of likely effects of the cap on interchange fees:

- First, booking and payment for accommodation and other pre-bookable tourism activities will shift from Costa Rica-based agents and acquirers to U.S.-based agents and acquirers. This will reduce margins for Costa Rican hotels and other tourism businesses.

- Second, higher–end tourists will likely spend less in Costa Rica because they will be less able to use their payment cards.

- Third, there will likely be an overall reduction in high-spending tourists visiting Costa Rica, with a concomitant reduction in total spending.

In 2019, Costa Rica received about 3.1 million visitors who stayed for one night or more, spending about $4 billion, roughly 6.25% of the country’s GDP.[21] The tourism industry employed more than 170,000 people, about 5% of the country’s working-age population.[22] Tourist numbers fell dramatically in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a dramatic decline in income and employment. Visitor numbers began to rise again in 2021 and, while total numbers remained below their pre-COVID highs, the number of visitors from the United States (245,000) was not far off the number for 2019 (280,000). In March 2022. Costa Rica announced its national tourism plan for 2022-2027, in which it sought to increase the number of annual visitors to 3.8 million by 2027, targeting tourism revenue of $4.8 billion.[23]

In 2019, Costa Rican merchants processed around 19 million cross-border payment-card transactions, with a total value of around $2 billion—representing about half the total tourism revenue and 16% of the value of all card transactions.[24] After falling in 2020, the number of cross-border payment-card transactions rose in 2021 to nearly 23 million, with a total value of $2 billion, which is consistent with the return of higher-spending tourists from the United States.[25]

If BCCR chooses to cap interchange fees on cross-border transactions at 1.25%, it is likely to impede Costa Rica’s national tourism plan, both by discouraging tourism and, more importantly, by reducing revenue from higher-spending tourists.

VI. Conclusion

Based on this assessment, there are significant costs associated with caps on cross-border MDRs and IFRs. As noted above, Legislative Decree 9831 permits BCCR to take into consideration such costs to the extent that they affect BCCR’s ability “to guarantee the efficiency and security of the card systems.”[26] As such it is incumbent on BCCR to consider the potential economic harm that is likely to arise if it were to lower the cap on cross-border IFR to 1.25%.

[1] Note, translations from the Spanish original are approximate.

[2] Julian Morris, Regulating Payment Card Fees: International Best Practice and Lessons for Costa Rica, International Center for Law & Economics (May 25, 2022), https://laweconcenter.org/resources/regulating-payment-card-fees-international-best-practices-and-lessons-for-costa-rica.

[3] Jean-Charles Rochet & Jean Tirole, Two-Sided Markets: A Progress Report, 37 Rand J. Econ. 645 (2006); See also Todd J. Zywicki, The Economics of Payment Card Interchange Fees and the Limits of Regulation, International Center for Law and Economics, ICLE Financial Regulatory Program White Paper Series (Jun. 2, 2010), available at http://laweconcenter.org/images/articles/zywicki_interchange.pdf.

[4] Bruno Jullien, Alessandro Pavan, & Marc Rysman, Two-Sided Markets, Pricing, and Network Effects, in Handbook of Industrial Organization (Vol. 4), 485-592 (2021).

[5] Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, & Marshall W. Van Alstyne, Strategies for Two-Sided Markets, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Oct. 2006).

[6] Id., at 33.

[7] Fijación Ordinaria de Comisiones Máximas del Sistema de Tarjetas de Pago 2021, Banco Central de Costa Rica, (Nov. 2021).

[8] Id. at 3.

[9] Alcance No 237 A La Gaceta No 212, Imprenta Nacional de Costa Rica (Nov. 7, 2022).

[10] Decreta: Comisiones Máximas Del Sistema De Tarjetas, No. 9831, Art. 15(j), Legislative Assembly of the Republic of Costa Rica, (“Cualquier otro elemento que razonablemente permita al Banco Central de Costa Rica garantizar la eficiencia y seguridad de los sistemas de tarjetas.”), http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?param1=NRTC&nValor1=1&nValor2=90791&nValor3=119755&strTipM=TC (last visited Apr. 12, 2023).

[11]Seventh Report on Card Fraud, European Central Bank 2022 (Feb. 1, 2022), https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/cardfraud/html/ecb.cardfraudreport202110~cac4c418e8.en.html#toc1.

[12] Id. SEPA refers to the Single Euro Payments Area.

[13] Id.

[14] Id. EA19 refers to the 19 EU member states that are members of the Euro zone.

[15] Zero Liability Protection, Mastercard (Oct. 17, 2014), https://www.mastercard.us/en-us/personal/get-support/zero-liability-terms-conditions.html; Zero Liability Policy, Visa, https://usa.visa.com/pay-with-visa/visa-chip-technology-consumers/zero-liability-policy.html (last visited Apr. 12, 2023).

[16] Visa EMV Chip Cards Help Reduce Counterfeit Fraud by 87 Percent, Visa (Sep. 3, 2019), https://usa.visa.com/visa-everywhere/blog/bdp/2019/09/03/visa-emv-chip-1567530138363.html.

[17] Card Issuers Accounted for 65.40% of Gross Losses to Fraud Worldwide in 2020, Nilson Report (Dec. 2021), Issue 1209, at 6.

[18] Jacqueline DeMarco & Poonkulali Thangavelu, A Guide to Foreign Transaction Fees, Bankrate.com (Feb. 24, 2023), https://www.bankrate.com/finance/credit-cards/a-guide-to-foreign-transaction-fees.

[19] Author’s personal communication with reservation specialist at Tortuga Lodge, April 2023.

[20] Mastercard 2022–2023 U.S. Region Interchange Programs and Rates, Effective April 22, 2022, Mastercard (2022), available at https://www.mastercard.us/content/dam/public/mastercardcom/na/us/en/documents/merchant-rates-2022-2023-apr22-2022.pdf; Visa USA Interchange Reimbursement Fees, Visa (Apr. 23, 2022), available at https://usa.visa.com/content/dam/VCOM/download/merchants/visa-usa-interchange-reimbursement-fees.pdf.

[21] OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022: Costa Rica, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2022), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/a99a4da2-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/a99a4da2-en.

[22] Id.; see also, OECD Economic Surveys: Costa Rica 2023, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2023), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/8e8171b0-en/1/2/2/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/8e8171b0-en&_csp_=0b8e1c4cf7b4fb558e396a4008a8398a&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book.

[23] Plan Nacional de Turismo de Costa Rica 2022-2027, Aprobado en la sesión N° 6210 de la Junta Directiva del Instituto Costarricense de Turismo, Apartado 3.II, celebrada (Mar. 21, 2022),English summary: Costa Rica: National Tourism Development Plan 2022–2027, Tourism Analytics, https://tourismanalytics.com/news-articles/costa-rica-national-tourism-development-plan-2022-2027.

[24] Supra note 9, Table 9. Assumes an average Colones:USD exchange rate during 2019 of 0.0017.

[25] Id. The Colones:USD exchange rate averaged around 0.0016 during 2021.

[26] Decreta: Comisiones Máximas Del Sistema De Tarjetas, No. 9831, Art. 15(j), Legislative Assembly of the Republic of Costa Rica, (“Cualquier otro elemento que razonablemente permita al Banco Central de Costa Rica garantizar la eficiencia y seguridad de los sistemas de tarjetas.”), http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?param1=NRTC&nValor1=1&nValor2=90791&nValor3=119755&strTipM=TC (last visited Apr. 12, 2023).